Adela García-Aracil, Ignacio Fernández de Lucio, Antonio Gutiérrez Gracia y Elena de Castro Martínez

Valencia the third largest city in Spain, on the Mediterranean, is an active industrial and commercial center producing textiles, metal products, chemicals, automobiles, furniture, toys, and colored tiles. Within the Spanish context, it belongs to the country’s main industrial centers, among which can be found regions like Madrid, Catalonia or the Bask Country. In socioeconomic terms, it could be considered as a peripheral region in the context of the European Union. Despite this, its position in terms of participation in national and European research programs is relatively low, especially when compared to the regions of Madrid and Catalonia.

The Valencia economy is based on a number of small and medium-sized firm structures, 67 percent of the industrial companies have less than 6 employees and 22 percent between 6 and 19 employees (INE, 2002). The Valencia level of R&D spending is even lower than the already low Spanish level, 0.6 and 0.9 percent of GNP, respectively (INE, 2002). At the same time, the Valencia economy is based on a number of traditional industrial sector, but lacks of science-based industries (for example, telecommunications) where their owners lacking modern business education or research traditions.

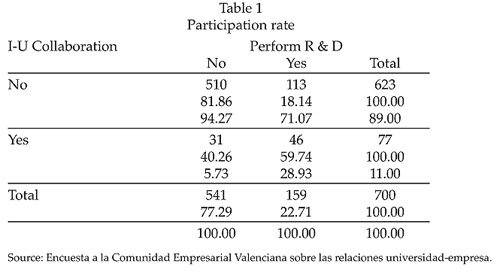

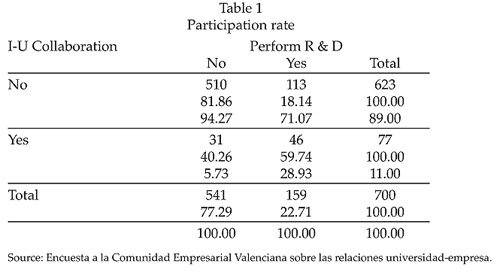

To analyze the impact of these region’s characteristics on industry-university interactions and R&D activities, data, for that purpose, were collected from 700 manufacturing firms surveyed in 2001, broken down between those belonging in sector activity from 15 to 36 NACE code and 64.2 sector activity (telecommunications). The response rate to the questionnaire was 38 percent. This may be taken as an indicator of the weak interest taking in the questions addressed by the Valencia firms. As we can observe in Table 1, 11.00 percent of the responding firms collaborated with one or more university and 22.71 percent performed R&D. However, 510 firms both did not cooperate with universities and did not perform R&D.

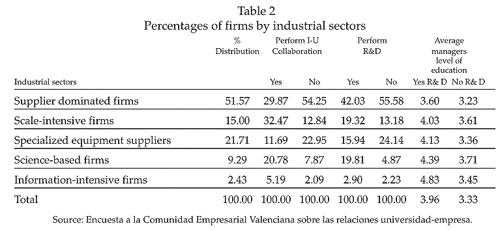

For our analysis, based on the Pavitt’s (1984) taxonomy and theory about technological linkages among different categories of firm, we aggregated the firms into five different groups: supplier dominated firms, scale-intensive firms, specialized equipment suppliers, science-based firms and information-intensive firms. Table 2 shows the percentage of firms in our sample by industrial sectors. Altogether, this percentage was the highest for firms considered as supplier dominated firms 51.57 percent. Specialized equipment suppliers accounted for the next largest group of 21.71 percent. Scale-intensive firms came next with 15.00 percent of firms and science-based firms with 9.29 percent. In contrast, the proportion of informative-intensive firms was relatively low, 2.43 percent.

Differentiation according to the performance of I-U collaboration is also shown in Table 2. Higher proportion of firms classified as supplier dominated firms and specialized equipment suppliers did not collaborate with any university, 54.25 and 22.95 percent, respectively. The opposite occurred in those classified as information-intensive firms, science-based firms and scale-intensive firms. The same pattern was found in those that engaged in R&D activities.

Based on the assumption about the importance of the firm capabilities, in particular, how managers coordinate and integrate activities within the firm to best utilize and enhance the knowledge and technology, information about the managers’ level of education is also presented on an ordered scale ranking from 1 (primary level) to 5 (higher education degree): main manager, product manager, R&D manager, administrative manager and other chief executive. Table 2 shows a positive relationship between managers’ level of education and R&D activities. The higher managers’ level of education, the more likely to engage R&D activities.

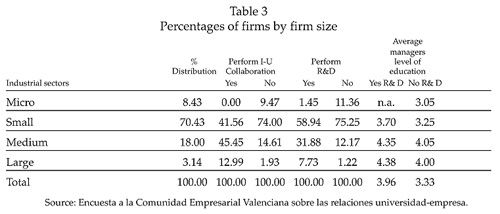

The same indicators as above were analyzed according to firm size (Table 3). This variable was measured by the number of employees within the firm. Micro firms were those having 10 employees; small firms those having from 11 to 50 employees; medium from 51 to 250 employees, and large those having more than 250 employees. Table 3 shows 70.43 percent of the Valencian firms were small and medium firms accounted for the next largest group of 18.00 percent. It is also observed a positive relationship between firm size and the performance of I-U collaboration, R&D activities and managers’ level of education, for example, the higher-sized firm, the more likely to involve in I-U collaboration.

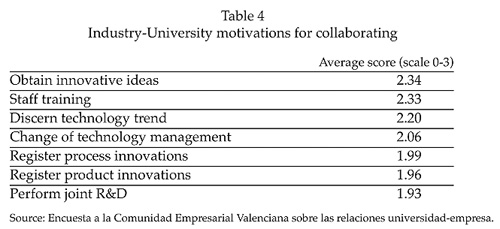

On the other hand, managers were asked to what extent several motivations for collaborating were the most important, ranking from 0 (not at all important) to 3 (most important). Table 4 shows that the level of importance was quite similar across motives. This latter finding is not surprising if we take into account that Valencian firms did not typically use university relationships that provide solutions to critical issues affecting central business areas and core technologies.

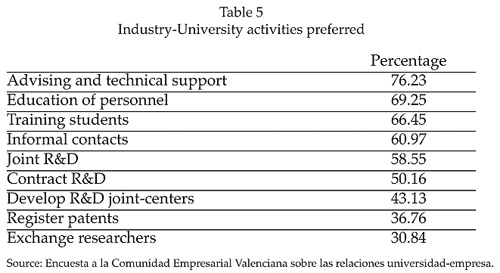

Finally, managers were asked to what extent several interactive activities were preferred to involve in I-U collaboration. In Table 5, we can observe according to the evaluation of the total sample that the advising and technical support was the most important interaction types between firms and universities. The low technological level that the Valencia industries have, could explain this finding. Education of personnel, students training and informal contacts were the next important I-U interaction types. Therefore, contract research was not the most activity preferred linking mechanism between industry and universities. A further interesting result was that managers rank collaborative research higher than contract research. An explanation would be that collaborative research would imply a bi-directional exchange of knowledge, whereas contract research was primarily a one-directional knowledge export from firms. The high ranking of informal contacts would support this high relevance of mutual knowledge exchange, too. On the same note, the low ranking of exchange researchers would support the weak relationship between industries and universities.