Espacios. Vol. 36 (Nº 16) Año 2015. Pág. 10

Mining in Colombia: A review of the calculation of Government Take

Minería en Colombia: Una revisión del cálculo de la Renta Minera

Eduardo Alexander DUQUE Grisales 1; Johann Carlos RAMIREZ Canedo 2; Juan Carlos RESTREPO Restrepo 3; Luis Diego VÉLEZ Gómez 4

Recibido: 23/04/15 • Aprobado: 22/05/2015

Contenido

2. Mining in Colombia: an overview

4. Case Study: Government Take Cerromatoso

ABSTRACT: Mining in Colombia has been highlighted as one of the main engines of economic growth. However, the lack of an efficient and transparent tax system has caused that the gain of some multinational corporations from the tax breaks offered by the government is higher than what they pay for income taxes and royalties. This paper reviews the extractive model proposed by the Government from the payment of mining royalties at Cerro Matoso S.A [5]. We concluded that the Colombian government should capture the mining rent, not as it is currently done through pithead value and the payment of royalties, but through charging a percentage on sales of minerals or companies' net profits. |

RESUMEN: La minería se ha constituido como uno de los principales motores de crecimiento económico en Colombia, sin embargo, la falta de un sistema fiscal eficiente y transparente ha dado lugar a que la ganancia de algunas multinacionales mineras, proveniente de las exenciones impositivas ofrecidas por el gobierno, sea mayor a lo que pagan en impuestos de renta y en regalías. En este artículo se hace una revision del modelo extractivista anunciado por el gobierno, a partir del análisis del cobro de la renta minera en Cerro Matoso S.A [5]. Se concluye que el Estado colombiano debería capturar la renta minera, no en boca o a borde de mina como actualmente se hace a través de la liquidación de regalías, sino mediante el cobro de un porcentaje de las ventas de los minerales o de las utilidades netas de las empresas. |

1. Introduction

The increasing demand for minerals experienced by the world during the last decade caused a rise in the price of raw materials to significant levels; this phenomenon also intensified the search and exploitation of non-renewable natural resources (NRNR) in various parts of the world. Given this, it can be mentioned that Colombia offers advantages in this field thanks to its vast mining and energy resources that can boost the country's economic growth through exports of mining.

Thus, extracting NRNR can indeed represent an effective opportunity for the country depending on how solid its mining institutions are and depending on the maximization of the mining income (Mining Government Take - MGT), plus an efficient use of these resources in generating sustainable economic development and social welfare. In mining, there are no reversible processes, just well timed moments. Each tonne of mined ore represents a reduction of Colombians' natural legacy. From an economic point of view, it is a part of the natural capital available to the country. Therefore, there is only one chance to transform such geological heritage into well-invested financial resources contributing to the country's economic growth and increasing life standards of Colombians. This exploitation can be done in a responsible way without severely affecting other natural resources such as water or the biosphere (Londoño, 2013; Brown, 2011). The amount of those financial resources depends on the taxes, royalties and compensations collected by the State in exchange for NRNR.

The rates of royalties established by Colombian Act 141 in 1994 do not reflect some of the aspects that are fundamental today. The rates received by the Colombian State from the exploitation of NRNR require reviewing since they should be consistent with applying higher tax rates for the use and manipulation of these resources tending to be scarce (Pardo, 2011). From the above facts, it is necessary to establish a long-term policy beyond this accelerated extraction occurring in the present in the country. It is necessary to assess NRNR with strategic criteria, including inherent basics to them like depletion and its lack of renewability. Mining taxing and royalties should respond to these demands and needs (Londoño, 2013).

This paper analizes several concepts and issues related to the Colombian mining - energy sector from economic, financial, social, cultural, environmental and legal perspectives enabling the analysis and holistic understanding of the current and future situation of it. This should contribute to a constructive discussion, the generation of knowledge and a sense of national belonging towards the NRNR in the communities surrounding the areas of existence and exploitation of these resources; it also should affect land tenure issues and the internal conflict in the country. Ecological consciousness should also be generated since there are many factors related to this activity that involve causing severe impact on the environment; it should encourage analysis on the consequences and risks from the economical and financial perpectives (which might not meet the Government's expectations). Based on economical and financial analysis, this paper seeks for pooling resources on the construction of a methodology leading to establish the adequate price (royalty) the Colombian state should stipulate for the exploitation of its NRNR; as well as, establishing how to capture mining taxes (through the payment of pithead value royalties or through charging a percentage on sales of minerals or companies' net profits).

This methodology will be used in the analysis of Cerromatoso S.A. This company has also been studied and discussed by several local actors. The above proposal would lead the State to capture out-of-the-ordinary income when mineral prices increase (as it has happened in recent years) so a sustainable policy can be created leading to boost the sector and the country.This article is the result of the research: "Propuesta metodológica para la valoración del Government Take de Cerro Matoso S.A." (A methodological proposal for assessing mining government take at Cerro Matoso S.A.).

2. Mining in Colombia: an overview

Mining, excluding oil extraction, is divided into four major groups: Non-metal minerals, metal minerals, precious minerals and combustible minerals. The most important ones in Colombia according to royalty income are the combustible minerals (fuels) mainly composed of carbon. Besides the above, Rudas & Espitia, 2013 state that ferronickel is the most exploited metallic mineral.

Figure 1: Mining sector in Colombia

Source: (Villareal, 2011)

Among the diverse actors directly related to mining, in the first place there are the operating companies that invest resources and assume the respective risks about the existence of an economically viable resource in the subsoil (investment in exploration) and about the variability of prices at medium and long term. Second, there are the owners of the subsoil, whether they are individuals (as is the case in countries like the US and Britain) or the State on behalf of the nation (as in most countries in Latin America, Africa and Europe). The owner of the subsoil also assumes risk from the uncertain behavior of market prices and bears the burden of negative effects (social, environmental and cultural) of extracting on other properties which are not adequately covered by the mine operator (Rudas & Espitia, 2013).

The relationship between the benefits and the costs of mining (both exploration and exploitation) is particularly complex (Baurens, 2010). Proper management of this relation depends largely on the rules that are set to ensure adequate compensation for the costs, both direct and indirect; as well as the rules that are set to distribute the benefits of the same activity (Rudas & Espitia, 2013).

2.1. Regulations, rights, internal conflict and mining

The implementation in Colombia of the extractive model of non-renewable natural resources driven by recent governments has been evident in the proliferation of mining rights and consistently, in the increase of mining activities around of the country. This situation has caused that various State agencies favor these extractive activities over other productive alternatives, and even over fundamental and collective people's rights (Negrete, 2013). In that sense, mining has become an activity that generates social, environmental, economic and cultural conflicts in several regions of the country (ABColombia, 2013) conflicts.

Despite the serious environmental and social adverse effect of mining in these times, in Colombia, mining rights are granted without any technical or legal rigor; that is to say, there is not a detailed qualification of the mining operators. This is so except with regard to the so-called strategic mining areas, where, according to the Mining Code, in order to grant mining rights, a very objective selection process must be conducted (a process which still lacks sufficient development) (Garay, 2013). The mining right granting and environmental licenses necessary to conduct businesses are not consistent with the determinations made in the planning, environmental and land use official instruments. Even some areas that are used for environmental conservation are then used for the development of mining and other sectoral activities (Carrillo, Rodriguez, & Forero, 2011).

Besides these activities are not subject to strict control by mining, environmental and territorial entities. Besides, the fact that these activities are considered public and social benefiting (by the Mining Code, Act 685, article 13, 2001), causes a number of social conflicts in many regions of the country. These conflicts are caused because various State entities are favoring such activities over the fundamental rights of communities and, therefore, ignoring the hierarchy of the rights provided by the law (Andrade Rodriguez, & Wills, 2012; Negrete, 2013).

It was estimated that by 2013, there were more than 19,000 mining rights applications. Those requests, plus the ones previously granted equal 22, 3 million hectares. Those rights were approved and assigned as "strategic mining areas" to the regions of Amazonas, Guainía, Guaviare, Vaupés, Vichada and Chocó [6] through Act 045 July 20, 2012 by Agencia Nacional Minera [7].

It may be noted that the country's mining interest areas cover about 40 million hectares out of the 114 million acres that make up the country. This entails that more than a third of Colombia's mainland has been granted as mining titles, has requested for certification or is intended for mining development through strategic mining areas. This constitutes itself an alarming figure since Colombia is the country with the highest biodiversity coefficient per square kilometer of the planet, and having into account that regulations for these activities are not effective enough to protect, safeguard and maintain adequately the NRNR and fundamental rights of the citizens of the country (Martinez, 2013; Negrete, 2013; Londoño, 2013).

2.2. Environmental permit mining

In 1993, Law 99, Article 50 defined environmental licenses as "the authorization granted by the competent environmental authority for the execution of activities subjected to the compliance (by the licensee) of the requirements stablished in the license related to the prevention, mitigation, correction, compensation and management of the environmental effects of the authorized activity "(Moreno & Chaparro, 2009).

In this regard and consistent with the provisions of the Constitutional Court [8], mining has come to be subject to environmental licensing because the very development of the business leads to a serious deterioration of the environment and natural resources and considerable changes in the landscape. Hence, Decree 1753 (1994) established the obligation for projects, works and activities to present prior environmental impact studies in order to grant environmental licensing, including exploration, extraction, beneficiation , transport and deposition. It is obvioius that all phases of mining should be subject to licensing, including exploration but this is not done in that way basically to boost foreign direct investment in the country (Negrete, 2013; L. Pardo, 2013).

However, Decree 501 (1995) eliminated the requirement of an environmental license for exploration and instead, the submission of an environmental management plan was established. The 2001 Mining Code did not alter this fact and established the requirement of an environmental license for exploitation activities within mining. Subsequently, Decree 1728 (2002) eliminated the requirement of an environmental license and the environmental impact study for the 47% of the previously required activities. As an alternative, it asked for a formal registration process upon the competent environmental authorities, compliying with environmental guidelines; that is to say, the survival of ecosystems is the least relevant issue since natural resources will be replaced by financial capital from development of the operating activities (Fierro, 2012; L. Pardo, 2013).

More recently, Decree 2820 (2010) kept up the licensing scheme excluding mining exploration. Citizen participation was reduced to merely inform those interested in license projects; there is not any possibility for the community's decisions to be considered as truly binding (Pardo, 2013). It is clear then, the accelerated flexibilization of environmental standards; for example, using the environmental guidelines as a tool for exploration, which are technical documents of conceptual and methodological guidance supporting environmental management of projects, however they are not instruments capable of assessing the environmental impacts of the exploration activity.

Now, in regard to environmental licensing, an analysis was conducted by the Comptroller General of the Republic, which shows the constant changes in the licensing criteria and their increasingly less rigorous approval; each time there are less subject-to-licensing activities and a very low rate of license rejection (Cabrera & Fierro, 2013).

3. Mining Rent in Colombia

The concept of mining rent (tax) is important to understand the concept of royalties generated by mining activities. These activities are seen as instruments to distribute financial gain between the mining agent (as an investor and manager of the production initiative) and the State (as having natural capital invested). In this respect, Stiglitz (1996) describes the economic rent as follows:

"Economic rent is the difference between the price that is actually paid and the price that would have to be paid in order for the good or service to be produced …Anyone who is in the position to receive economic rent is fortunate indeed, because these "rents" are unrelated to effort…".

Applying a conventional economic efficiency criterion, the various factors of production (labor, financial capital and natural capital) should receive a compensation equivalent to their marginal productivity. For a particular entrepreneur, the retribution to this specific mining investment must equal the minimum anount to enter (or stay) in the respective activity. For the State, the minimum compensation for their contribution of non-renewable resources must also be equal to the opportunity cost of its property, that is to say, the mineral; and, in practice, it must be greater or at least, equal to what any other investor had offered in order to access that resource.

Despite representing revenue for the State, the concept of retribution from investment in NRNR should not be mistaken for the concept of royalties collected by the State from taxes (such as income tax or value added tax). Unlike taxes, such retributions do not generate distortions in the allocation of investment resources because it simply represents the normal compensation from a part of the resources invested, namely: non-renewable natural resources essential for the development of mining. A suitable scheme to reward NRNR investment owned by the federal government and administered by the State and the investor is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: State and private inversor's participation.

Source: Adapted from (Rudas & Espitia, 2013).

Then, there is the obligation to distribute rent income among the various contributors to the investment according to the origin and parts of each contributor in the total investment. This is done in order to determine if their existence is due to the operating agent's specific factors (such as greater efficiency in production processes) or due to the conditions of the resource provided by the State (the reservoir's richness or a better location from consumption centers), or even if it derives from external factors (higher prices caused by a growth in global demand).

3.1 The Colombian mining - energy rush

An improvement in the conditions for investment and a promising perspective in the mining and energy sector has generated a significant increase in investment in this sector. It went from a US $1b in 2001 to US$ 5,700b in 2009, representing a growth of 450%. During the Tenth International Mining and Oil Congress, Cinmipetrol, the current Minister of Mines and Energy, Mr. Amylkar Acosta Medina stated that "Colombia had an exceptional behavior. According to figures from Banco de la República*, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) did not decrease but reached a record of US$ 16,722,000 m in 2013; what is striking is that the largest percentage of this investment was allocated to the mining and hydrocarbons sector, a 81,6%, US$ 13,736 million". (Rudas & Espitia, 2013).

Under this scenario, challenges to macroeconomic and microeconomic levels are raised. At a macro level, the Government must ensure the stability of the economy and face the pressure revaluation brings so that a competitive exchange rate can be maintained. Among the proposed alternatives, there is the implementation of a fiscal regulation, accompanied by a stabilization fund to adjust the fiscal balance and provide the ability to save the surplus from the mining - energy bonanza in foreign banks. On the other side (avoiding the waste of resources that by their nature could prove to be temporary), a restructuring of the royalty regime should be implemented. It should lead toward achieving greater interstate and intergenerational equity; a more robust institutional framework to ensure the appropriateness of their use and a macroeconomic stability (Otto, 2006).

At a microeconomic level, the Government must define guidelines for the use of the resources derived from this bonanza, so that it can be "planted" and future generations can also benefit from this increased temporal flow of income. In other words, these resources should be destined for investment in productive developments that generate higher future income streams. The country would have two non-exclusive alternatives for productive development: first, promoting linkages (or clusters) of high added value around the mining and energy sectors. Second, encouraging sectors or clusters that are not related to mining and energy sector. Whatever the strategy adopted by the country, it requires efforts of institutional strengthening to implement productive development policies in this path (Otto, 2006).

Moreover, mining and energy sectors development unaccompanied by institutional adjustments could result in a greater waste of royalties (like witnessed so far in the form of increased levels of corruption and violence rates).

3.2. The Tax advantages to mining

The tax regime in Colombia is characterized by its intricate complexity and poor control from the State (companies are not strictly obliged to submit detailed information on their tax returns), which causes lack of transparency. In addition, a wide range of discounts, rebates and tax exemptions are applicable in the Ccountry's income tax legislation. Fiscal rules include the following tax benefits in income tax (Rudas & Espitia, 2013):

a) Special deduction for investments in fixed assets. Between 2004 and 2007 natural and legal persons could "get a 30% deduction in the income tax only once in the fiscal period from the cost of investments made through the acquisition of real productive fixed assets" (Decree 1766, 2004). This deduction was increased to 40% from January 2007 (Act 1111, art. 8, 2006) and further reduced again to 30% in 2010 (Act 1370, art. 10, 2009). As of the fiscal year 2011, this benefit is eliminated, but it is stated that those who have applied for legal stability contracts will be able to keep the benefit for three more years (Act 1430, art. 1, 2010).

b) Deduction for the obligatory payment of royalties. Royalties constitute the State's participation in the benefit resulting from the use of non-renewbable natural resources in return for its rights as the owner of the subsoil. Therefore, they are neither a tax nor a cost of production but the State's participation in productive investment. For tax purposes, since 2005 DIAN [9]changed its previous interpretation and stated that they could account as income of a third party, non-constitutive of taxation, not as a distribution of surplus as in the case of hydrocarbons through the National Hydrocarbons Agency (NHA); or it can be deducted from net income as a cost of production, also non- subject to income tax, as with the rest of minerals (NTS [10] Article 116).

c) Deduction for depreciation of fixed assets. The depreciation due to normal deterioration or obsolescence of assets used in rent-producing businesses usually count in terms of up to twenty five years. However, the tax regulations establish that, if the taxpayer finds the lifecycle set in the tax code inappropriate (or that it does not match his/her particular case), a new a different lifecycle can be set and increase speed of deductions; even periods less to 3 years can be set (with the approval of DIAN). Additionally, the speed of depreciation can be increased even more if assets are employed in more than one shift per day (NTS, Articles 128, 134, 135 and 137).

d) Deduction for amortization of investments. In addition to the depreciation of tangible fixed assets, in each period, the producer may deduct the amortization aliquot from its non-depreciable investments such as acquisition, exploration or exploitation costs of non-renewable natural resource investments. This repayment must be made within a period not less than five years, unless it is shown that, by the nature or duration of business, amortization should be paid in a shorter period. Additionally, in cases where exploration is unsuccessful, the amount of investment will be amortized in the year in which such status is established, no later than within two years of its implementation (NTS, Articles 142 and 143).

However, these tax advantages are beyond the income tax to the extent that there are prevailing rules excluding mining from other taxes. This is how the Mining Code (Act 685, 2001) originally established in Article 229 that the payment of royalties was "incompatible with the establishment of national, regional and municipal taxes on the same activity, whatever their denomination, modes and features ". The Constitutional Court declared unconstitutional that incompatibility and reiterated the jurisprudence of the royalties' nature and their difference from taxes; it stated that "royalties and taxes are different figures that have a constitutional foundation and different purposes" and that "royalties are represented by what the State receives for granting rights to exploit non-renewable natural resources which it owns (CCC Article 332 [11]), because these resources are limited".

Despite these regulations, mining remains excluded from paying taxes to entities such as the Superintence of Industry and Trade, since the Mining Code establishes in Article 331 that "mining exploration and exploitation, the minerals obtained in mines (pithead), machinery, equipment and other items that are needed for such activities will not be taxed with regional and municipal direct or indirect taxes." Hence, the restructuring to the system of royalties and their distribution among local authorities with different criteria to their place of origin will lead to the municipalities assuming all risks for the negative consequences of this activity on the social and environmental conditions; there will not be major advantages in terms of tax revenue, since municipalities will not receive royalties nor they will get the industry and trade tax that should paid from this activity.

Specifically, tax expenditure (defined as the reduction of income tax payable by companies). It expresses a significant gap between the income tax actually accepted by companies and the tax these companies would have had to pay if there were no exemptions, deductions and discounts granted by the tax system. A relevant aspect in all cases is the effect caused by deductions and discounts on various specific sectors.

The structure of those discounts is difficult to identify due to the lack of transparency in tax statements. Indeed, it is possible to identify that in addition to the ordinary deduction of direct production costs, mining companies reported additional deductions from taxable income for the concept of "operational expenses and sales management", which represented an annual cost to the country of COP$483 billion. In turn, the special deduction for investment in fixed assets of these companies represented an average of COP$164 billion annually; contrasted with the deduction of royalties as production costs from coal, which implied a public finance detriment of COP$377 billion annually. However, according to way as other deductions are presented, it is not possible to identify the specific source of additional cost to the national treasury (of about COP$1.2 billion annually) for each of these six years. This is a clear sign of the embezzlement the country is experiencing from its NRNR; there are no actions facing this situation, on the contrary, the country is being promoted as a world power in mining.

In summary, it can be stated that the tax benefits granted by the current tax system in recent years in Colombia has generated a decrease in collecting income tax on mining and hydrocarbons that far exceeds the amount of the royalties generated by these sectors.

4. Case Study: Government Take Cerromatoso

The Cerro Matoso is an elevation of 200 meters high, located in San Jorge River's basin at the municipality of Montelíbano (Córdoba region). The nickel deposit found there was discovered in 1940 by Shell Oil Company (MEPU [12], Mining and Energy Planning Unit, 2009). In the mid-fifties, Richmond Oil Company requested and obtained the rights to it and started exploration activities in 1958. Between 1967 and 1970, the rights were transferred to Hanna Mining Company; later, this company negotiated the concession contract with the Colombian Government (Rudas, 2010).

In 1970, "Econíquel" was founded. A State counterpart of the project that initially owned the third part of it. The exploration phase lasted until 1976, the year in which the technical and economic study for implementing the mining project (MEPU, 2009b) was conducted.

The exploitation phase begins in 1979 with the participation of IFI, Conicol SA [13] and Billington Overseas Ltda. These companies consolidated the company known as Cerro Matoso SA. Between 1978 and 1980 the project funding was obtained and detailed designs were made. Between 1980 and 1982 the mine preparation, construction, assembly plant and fit testing were performed. In 2005, Cerro Matoso SA became the property of the Anglo-Australian company BHP Billiton, which holds 99.9% stake (the remaining 0.1% belongs to the solidarity sector and the employees). From 1982 to date, the company Cerro Matoso SA has continuously been producing ferronickel from Cerro Matoso (De la Hoz, 2009). The mining here combines a high quality nickel deposit with low cost ferronickel smelting. This makes it one of the producers of ferronickel with lower costs in the world.

In this area, ferronickel extraction and its industrial processes are developped. The material is extracted through open-pit mining and stored in piles. Then, it is conducted to a crushing zone and it is mixed with several minerals of various qualities (in terms of nickel percentage). Next, there is the industrial stage; the material is led to a smelter located near the mine. Through the melting, ferronickel pellets of high purity (37.5% nickel) are produced with low carbon contents (which is used to produce stainless steel). The slag generated from the smelting and also deposited in piles can be reprocessed; this is why it should be considered as part of the mineral primary offer being susceptible of demand in the industrial processing center located at the minehead (Rudas, 2010).

There are not distinguishing reports on the two processes for accounting purposes of the cost of the product and royalty payment. This means that the payments this company makes to the State (taxes and royalties) are being underestimated, being the only one company that extracts such material in the country (MEPU, 2009a).

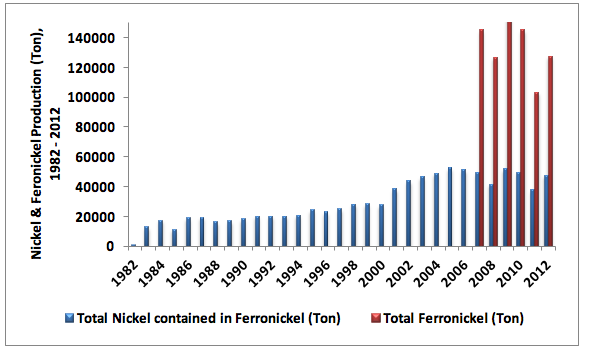

4.1 Nickel Economics

The exploitation of Cerro Matoso's ferronickel has placed Colombia as one of the largest producers of this product in the world. In the last 30 years, the extraction activities of ferronickel and nickel has presented sustained growth. The production of nickel and ferronickel started in 1982. Nickel production increased from about 20,000 tons in 2000 to 50,000 tons in 2010. Similarly, production of ferronickel production has decreased from almost 145,000 tons in 2007 to 113000 tons in 2012 (Figure 3). This, as a result of the increase in raw materials and pure minerals in the international market of commodities.

Figure 3: Nickel and ferronickel production, 1982 - 2012

Source: (MEPU, 2013).

According to the DIAN statistics, Cerro Matoso SA, as the only firm that produces ferronickel in Colombia, has been increasingly stating income taxes in current COP rates, increasingly. As a proof of this, while in 1995 declared an average of COP$ 55 billion per year, this figure increased in subsequent years to more than COP$ 200 billion annually (2000-2004) and more recently to over COP$ 400 billion per year (2007- 2010). However, it appears that the potential tax generation is even greater (Rudas, 2010).

4.1 Royalty Control by the State

In the Colombian context, royalties are the economic compensation due to the State for the exploitation of non-renewable natural resources. This should be used to finance projects of social, economic and environmental development by local authorities; to save for their pension liabilities; for physical investment in education; for nvestments in science, technology and innovation; to generate public savings; to supervise the exploration and exploitation of deposits and to know the geological mapping; and to increase the overall competitiveness of the economy leading to improve the social conditions of the population.

The current version of the National Constitution, as amended by Legislative Act 5, 2011, the General System of Royalties created a detailed scheme for the distribution of royalties among all territorial entities of the country. It was made through four funds. Among them, royalties are distributed with restrictive, inflexible and rigid allocation percentages. These are: the science, technology and innovation fund, the regional development fund, the regional compensation fund and the savings and stabilization fund (see Article 361 of the CCC).

Concession contracts are allocated through the respective mining title applying the right of priority established the principle of "first in time, first in right". Likewise, a system of rates is set by a static royalty regime with fixed percentages, without any consideration concerning high prices, above historical, where the licensees obtain extraordinary gains with very little benefit to the State (owner of the resources). In the case of hydrocarbons, the allocation process is done in an open and transparent manner through public auction rounds and assigning the concession to the best technical and financial offer. Similarly, specific conditions of an additional retribution to the State are included for those economic situations in which prices are above the historical trend (Rudas, 2010).

In this regard, Azurero (2011), professor at Universidad de los Andes, wonders whether it would be preferable that the State auctioned the right to mining among several bidders, to assign it to anyone willing to pay higher royalties; and concludes that "this would give more transparency to the selection of the operating companies, would end the horrible habit of automatic extentions which emerge whenever the term of a mining lease expires, and could increase the amount of funds received by the State. "

The mining sector is chartered by a series of exceptional regulations and privileges that seek to exclude this activity from general norms that every citizen and every productive activity must meet compulsorily. Concepts have been issued by the tax authority that allow discounting mining royalties as production costs and not as tax obligations to repay the State for the use of public assets. There is also an evident weakness of the mining authorities for adequate monitoring and controlling financial compensations such as the in-surface rent (paid during the exploration stage) and royalties (valid during the operational stage). This is clearly expressed by the Ministry of Mines and Energy when it proposes unifying criteria on how to interpret and apply national legislation (Rudas, 2010).

The mining sector in Colombia experiences all these drawbacks and shortcomings today. Thus, it is necessary to analyze and review policies and laws that currently rule this situation to approach the solution to these with new proposals. People are working hard on this subject in the country and the goal is to contribute to the achievement and consolidation of a long-term policy coherent with the benefits to be obtained for the country from mining.

4.1.1 Nickel Royalties in Cerromatoso SA

Contract 886 (30 March, 1963) signed between the Ministry of Mines and Oil and the Richmond Oil Company (after multiple modifications) allowed Cerro Matoso SA to explore and exploit deposits of nickel in Montelíbano until September 30, 2007. Through an amendment signed on October 10, 1996, the contract was extended for five more years: the period from October 1, 2007 until September 30, 2012. Thus, Cerro Matoso SA has been required to pay quarterly royalties to the State, calculated as follows (Rudas, 2010):

a) Until September 30, 2007, royalties are settled to 8% of the product's pithead value in accordance with the contract terms. Pithead value is calculated based on the daily arithmetic average price in the international market using the official exchange rate of the dollar and discounting internal and external transport costs (100%), processing costs (100%) and all other costs and depreciation of investments after exploitation of the mineral; this is done as specified in the 16th clause in the additional contract of July 22, 1970. It states that, whatever the international price, minimum royalties will be 8.7% of production costs (mining, primary crushing, recovery and mixing ...).

b) Since October 1, 2007, Royalties are paid in accordance with the provisions of Act 141, 1994, for an amount equivalent to the 12% of the pithead value of crude nickel mined. The pithead value is calculated based on the average FOB price in Colombian ports in the immediately preceding quarter and discounting 75% of the oven's processing costs, handling costs, transport costs and port costs.

In 1973, through Act 13 the Regional Autonomous Corporation of Sinu and San Jorge Valleys [14] (CVS) is created. And all royalties transferred by way of the nickel mine at Cerro Matoso this corporation. This decision is amended by Act 36 of 1989, which establishes a share of the municipalities of San Jorge 40% of the total royalties as well: Montelíbano, 20%, Ayapel, 5%, Puerto Libertador, 4%; Planeta Rica, 4%; Pueblo Nuevo, 4%; and Buena Vista, 3%.

The total amount of received royalties from Cerro Matoso are transfered to this corporation. This decision was modified through Act 36, 1989, which establishes a 40% participation to San Jorge River's municipalities as follows: Montelíbano 20%, Ayapel 5%, Puerto Libertador 4%, Planeta Rica, 4%, Pueblo Nuevo 4% and y Buena Vista 3%.

Based on those regulations and subsequent amendments to the General Royalty Law and the National Royalty Fund during 1990 to 2012, the deposits provided by Cerro Matoso SA were distributed between the beneficiaries required by the law as shown below.

Table 2: Total distribution Cordoba's State Institutions (MEPU, 2013)

NÍQUEL |

|||||

DISTRIBUCIONES ENTES TERRITORIALES DE CÓRDOBA |

|||||

AYAPEL |

BUENAVISTA |

MONTELÍBANO |

PLANETA RICA |

PUEBLO NUEVO |

PUERTO LIBERTADOR |

$ 42.545.508.051 |

$ 26.459.404.978 |

$ 243.590.804.916 |

$ 42.335.094.310 |

$ 37.043.028.131 |

$ 47.624.753.832 |

Figure 4: Percentages of total distribution Cordoba's State Institutions

Source: (MEPU, 2013)

A curious fact which deserves to be highlighted: in 2011, Ingeominas [15] forced Cerromatoso to pay more than COP$35 billion for unpaid royalties applying unauthorized discounts (Robledo, Jorge Enrique, 2012b). Another curious fact is what happened in Montelíbano. In 2008, this municipality received only COP$ 21,571 million (of the COP$ 35,525 due to it); in 2009, it did not received any amount; in 2010 it just received 432 million (of the COP$ 22,223 allocated); and in 2011, it received COP$ 4,962 million (of the COP$ 36,026 allocated) (Pardo, 2011).

Finally, major inconsistencies can be observed today leading to the detriment of the high level of revenue the State would be receiving from the startup and capitalization of its NRNR. Particularly, in the case of nickel, it is well worth scrutinies in terms of the laws, socio economic and especially from social and environmental standards since they are not accurately assessed in any mining process (which eventually may not be fully sustainable).

4.2 Different methodologies for the calculation of the Government Take (GT)

According to iterature, mining rent is estimated as the difference between the prices of the production (at international prices) minus the production costs. The first component (the production's price) is calculated by multiplying the production's volume traded in the financial market by the international price of the natural resource (Villareal, 2011; Fraser, 1999).

For the second component (the production costs), there are three methods of calculation:

a) Named C (1) includes the following items: mine cost, plant cost, overheads and selling expenses.

b) Named C (2) which includes the C (1) items plus the depreciation and amortization (fixed assets).

c) Named C (3) which includes the C (2) plus the financial expenses.

Figure 5: Methodologies for the calculation of the mining production costs

Source: (Villareal, 2011)

4.3. Cerromatoso's Government take

Cerro Matoso is a pioneer in Colombia's mining and metal industry. During its thirty years of operations, it has become the world's sixth largest producer of ferronickel. It has exported around 910,000 tons. The economic performance of the nickel industry is very vulnerable to the behavior of metal prices. During the last two years, prices have been low due to a slowdown in demand for commodities, especially in Europe and the overproduction of nickel in China. This reflects the continued investment in exploration, improved operation, health, safety and the environment, as well as the distribution of benefits among shareholders, the State, providers and communities (CMSA, 2012).

During the second half of 2011, the revision made to the formula for calculating royalties initiated by Ingeominas in 2010 was completed. As a result of this exercise calculation and payment of royalties were reviewed from 2004 to 2008, and thereafter. The payment made by Cerro Matoso resulting from this review was COP $ 35,000 million.

In October 2008, Ingeominas jired the firm BDO to audit the calculations and payments Cerro Matoso made during the period between 2004 and 2008. The audit said that the costs of San Isidro Foundation, Panzenú Foundation, Montelíbano's Educational Foundation, clubs and citadels were not to be deducted as expenses for purposes of calculating royalties [16] . It was also agreed that the depreciation of assets should be made according to the original contract and not to the accounting depreciation, which is audited annually by the DIAN (CMSA, 2012).

Having established (jointly with Ingeominas) a unique interpretation for calculating royalties during the period 2004-2008 and extrapolation of the findings until 2011, Cerro Matoso paid COP $ 35,000 million in August 2011; from that amount, COP $ 24,907 million were the differences found from 2002 to March 31, 2011; and COP $ 10,564 million corresponded to the money's value upgrade over time. The Mining authorities and Cerro Matoso agreed a unique interpretation for calculating royalties settlement giving a solution to the different ways of interpreting costs and expenses applicable and / or deductibles (Cerro Matoso SA, 2012).

According to August 5, 1985 Agreement - Contract 866 for Quarterly Calculation of Mining Royalties, the following bases (BDO AUDIT AGE SA, 2009) were adopted:

R= 8%xVbm (1)

Vbm=(Ln x Pr x Tc)- Ca (2)

Meaning,

R = Royalty

Vbm = Minehead value of crude ore mined nickel.

Ln = pounds of nickel processed in the quarter.

Pr = Transfer Pricing: Simple average of nickel prices registered at the London Metals Exchange and at free markets in Europe and America, calculated as follows:

a) London Metals Exchange: the monthly average price per pound of nickel will be taken in US dollars for purchases in cash, as it appears in "Metals - Week".

b) Free Market in Europe: the monthly average of the lowest prices and the monthly average of the highest contributions will be taken in US dollars for the sale of "Melting" type nickel registered in the "Metal Bulletin" under the tag "Non-Ferrous Primary Metals".

c) Free Market in America: the monthly average of the 10 lowest quotations and the monthly average of the highest contributions will be taken in US dollars for the sale of "meeting" type nickel registered in the "Metals Bulletin" under the tag "Non-Ferrous Primary Metals".

d) The previous five averages will be monthly averaged, and the resulting monthly average will be taken as the basis for calculating the quarterly average.

e) For these purposes, the averages will be calculated quarterly.

Tc = an arithmetic rate of the official Exchange Rate for converting US dollars to Colombian pesos, registered for the respective quarter.

Ca = Applicable Costs: The "internal and external costs of transport, processing costs and those costs that are caused after the exploitation of the mineral" established by the sixteenth clause in the Additional Contract.

Moreover, we proceeded to build two more detailed indicators of the distribution of the final value of mineral production in Colombia as well (Rudas & Espitia, 2013):

First, a distribution indicator of the production's total amount between intermediate consumption (CI) and the value added composed by the remuneration to labor and the operating gross surplus (before any transfer to the State). Second, a distribution indicator of the exploitation gross surplus (as a proxy of mining income [17]) between the benefits for the producer, the taxes paid to the State and the royalties (or State's rent).

Having these indicators as a starting, it is then possible to calculate the State's participation in the mining income generated by Cerro Matoso's operations, which is obtained through two instruments:

- Taxes; consisting mainly of the income tax, the value added tax (VAT) and the wealth tax [18].

- Royalties, understood as the State's income themselves include both the economic rent (scarcity rent) and the comparative advantage rent (e.g. the deposits' conditions and price booms). Unfortunately, they do not count as natural compensation natural to the capital used in the mining activity.

As shown in Figures 6 to 9, the exploitation's gross surplus from 2000 to 2011 ranged from approximately 50% to 63% of the total value of the product concerned (nickel). In turn, the labor compensation's share in the total product's value for nickel ranged between 7% and 13%.

In terms of the distribution of gross operating surplus (equivalent to the total value of each product minus the returns to labor and less intermediate consumption), the figures presented speak for themselves. For nickel such participation during the period considered was from 11% (in 2002, when the lowest prices of the period were presented) and 52% (in 2007, the year of the highest prices during the same period) (Vicente et al., 2011).

In terms of the distribution of the exploitation's gross surplus (equivalent to the total value of each product minus the labor compensation and the intermediate consumption), the figures presented speak for themselves. For nickel, such participation was from 11% (in 2002, when the lowest prices of the period were presented) and 52% (in 2007, the year of the highest prices during the same period) (Vicente et al., 2011).

Figure 6: Distribution of production's total value ($) for Cerromatoso S.A.

Source: (Rudas & Espitia, 2013)

-----

Figure 7: Distribution of production's total value (%) for Cerromatoso S.A.

Source: Retrieved from (Rudas & Espitia, 2013)

------

Figura 8: Mining rent's distribution ($) for Cerromatoso S.A.

Source: Retrieved from (Rudas & Espitia, 2013)

------

Figura 9: Mining rent's distribution (%) for Cerromatoso S.A.

Source: Retrieved from (Rudas & Espitia, 2013)

Indeed, what the country received in terms of mining revenues (other than taxes paid by Cerro Matoso S.A.) during the last year (2011 data availability) was only 18% compared to the profits after taxes for this company (66% in the same year). During the analyzed period (2000 - 2011), that percentage fluctuated between 5% and 18%, below the huge profits allegedly obtained and transparently reported to the State authorities (Vicente et al., 2011).

4.4 Analysis of Results

Indeed, under the new 2001 mining code, the suggested percentage for calculating royalties from nickel is 12% (not 8%). It is known that paying minehead value royalties is not profitable for the country because there are defects in transferring prices and benefits would not be gained when ore prices increase in the described markets. A new formula should be designed for the settlement of royalties. It must be based on the companies' profits, not based on minehead value royalties. Thus, it would not be possible to mask the payments through foundations created by the operating businesses (this should actually be in force in social responsibility policies).

Studying other Latin American economic models, it is clear that Colombia has not implemented an effective model to collect natural capital compensations from mining; there are no royalties received from the use of the environment, the air, the water, the land and the negative side effects that the residents near the exploitation areas suffer. The country's current GDP structure does not allow to assess these environmental services provided by nature since it only takes into account the financial impact when approving mining processes.

From the analysis of the current mining rent addressed to the State by Cerromatoso, some ideas regarding the system arise:

- Firstly, regarding the negative effect of current fixed royalty rates, indepently from the prices, it is necessary to amend this system and replace it with another one, which at a certain price level (a profitable one), it can establish an increasing rate proportionally to the growth in prices.

- Secondly, the equally perverse principle of "first come, first served" currently applied to allocate public subsoil resources to private operators should be replaced by a system that ensures greater autonomy from the State to select the mining operator.

- Thirdly, one of the key criteria in selecting mine operators (but not the only one) should be to favor the best offer in relation to the variable part of royalty rates; and of course, the variable part of the contractual compensations offer over the royalties defined by the Law (like the "highest bidder" as it is currently applied in Colombia's hydrocarbon sector).

Additionally, Act 141, 1994 (article 16) on the Royalty Regime must be urgently modified (Rudas & Espitia, 2013):

The Article that currently sets the rates of royalties in Colombia states:

ARTICLE 16. Amount of royalties. May the following table be established as royalty rates for the exploitation of the country's non-renewable natural resources on production's headmine value:

- Coal (exploitation higher than 3 million tons per year) 10%

- Coal (exploitation lower than 3 million tons per year) 5%

- 12% Nickel

- Iron and copper 5%

- Gold and silver 4%

- Alluvial gold concession contracts 6%

- Platinum 5%

- Salt 12%

- Limestone, gypsum, clay and gravel 1%

- Radioactive Ore 10%

- Metal ore 5%

- Non-metallic minerals 3%

- Building Materials 1%

The following amendment (replacement) is proposed:

ARTICLE 16. Amount of royalties. It is established a minimum royalty rate caused by mineral resources intended for exporting equivalent to 12% of a base value corresponding to the 80% of the FOB cost in Colombian ports.

This minimum royalty rate will apply provided that the daily international average price of the preceding month to the date of export is less than or equal to a historical average reference price, calculated as follows:

- Based on the daily series of prices published by the London Metal Exchange, monthly averages of the immediately preceding 30 years are calculated.

- The average prices corresponding to these 360 months are classified from lowest to highest.

- The average price of the 270 months corresponding to the first three quartiles of months with the lowest prices is obtained.

- This average is assumed as a historical reference price for all registered exports during the current year.

- At the end of each year, this calculation is updated including the last past year, eliminating from the series the first year.

If the daily average international price of the immediately preceding month to the date of export is equal to or higher than three times this historical average price of reference, a maximum royalty equivalent to 50% of the base value corresponding to the 80% of FOB value of exports placed in Colombian ports is then applied.

If the daily average international price of the immediately preceding month to the date of export is strictly higher than the historical average reference price and strictly lower than three times this same historical average reference price, a percentage (growing between the 12% of the minimum royalty and 50% of the maximum royalty) will be applied.

5. Final comments

Colombian State's low benefitting from mining revenues, both in normal pricing situations and when price booms occur, raises the need for reviewing pricing mechanisms for public participation rates through royalty mechanisms.

It is necessary to strengthen fiscal control exerted by the Comptroller General of the Republic and Dian through detailed analysis and assessing income statements presented by contributors. This is a priority due to the lack of transparency existing in the current tax system, and the low quality of the information declared to DIAN by those companies; also, due to the various deductions and exemptions companies invoke, which promotes elusion and evasion mechanisms. Thus, strengthening the fiscal control on DIAN would improve the efficiency of raising funds for the State.

Control and effective monitoring of economic, social, environmental and tax impacts of mining at territorial level is required. Despite of the relevance mining represents in terms of its contribution to the country's GDP and to the generation of tax revenues, the dominant role is not reflected in the conditions for regional development. Poverty levels (and in some cases, violence) in most mining areas of the country, reflect the inefficiency of the State to allocate effectively the resources from royalties concentrated on producing areas.

All this requires great national unity in defense of the public sector, and this must unite all sectors to jointly establish long-term strategies for the development of the country through this sector and other sectors related to our mining economy.

6. Bibliography

ABColombia. (2013). Regalándolo Todo: Las Consecuencias de una Política Minería no Sostenible en Colombia. Tomado de http://www.abcolombia.org.uk/downloads/Giving_it_Away_mining_report_SPANISH.pdf

Andrade, G. I., Rodríguez, M., & Wills, E. (2012). Dilemas Ambientales de la Gran Minería en Colombia. Revista Javeriana, Junio, No785, 17-23.

Baurens, S. (2010). Valuation of metals and mining companies. Institut für Banking and Finance - CUREM.

BDO AUDIT AGE S.A., I. (2009). Informe de la Auditoría Contable a Cerro Matoso S.A. en las Vigencias 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 y 2008 en Relación con los Denominados «Costos Aplicables y Costos Mineros» Empleados para el Cálculo de las Regalías.

Cabrera, M., & Fierro, J. (2013). Implicaciones ambientales y sociales del modelo extractivista en Colombia. Minería en Colombia, 89.

Carrillo, F. E. V., Rodríguez, E. G., & Forero, E. D. (2011). El sector extractivo en Colombia.

CMSA. (2012). Reporte de Sostenibilidad CERRO MATOSO S.A. FY 2012.

Campodónico, H. (2008). Renta petrolera y minera en países seleccionados de América Latina. CEPAL, Documento de Proyecto de la División de Recursos Naturales e Infraestructura, Septiembre. Recuperado a partir de http://www.cepal.cl/publicaciones/xml/6/34616/lcw188e.pdf

CEPAL - Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. (2012). Rentas de Recursos Naturales No-Renovables en América Latina y el Caribe: Evolución 1990 -2010 y Participación Estatal. División de Recursos Naturales e Infraestructura.

De la Hoz, J. V. (2009). Cerro Matoso y la economía del ferroníquel en el Alto San Jorge (Córdoba). Aguaita - Revista del Observatorio del Caribe Colombiano, 19-20, 41.

Fierro, J. (2012). Políticas mineras en Colombia. Bogota: Instituto para una Sociedad y un Derecho Alternativos ILSA.

Fraser, R. (1999). An analysis of the Western Australian gold royalty. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 43(1), 35–50.

Garay, L. J. (2013). Minería en Colombia. Fundamentos para superar el modelo extractivista. Bogotá: Contraloría General de la Nación.

Londoño, V. (2013). Colombia no está preparada para la locomotora minera. Bogotá D.C. Recuperado el 6 de mayo de 2013 a partir de www.elespectador.com

Martínez, A. (2013). Estudio sobre los impactos socio-económicos del sector minero en Colombia: encadenamientos sectoriales.

Moreno, C., & Chaparro, E. (2009). Las leyes generales del ambiente y los códigos de minería de los países andinos. Instrumentos de gestión ambiental y minero ambiental. CEPAL.

Negrete, R. (2013). Derechos, minería y conflictos. Aspectos normativos. Minería en Colombia. Fundamentos para superar el modelo extractivista. Bogotá, DC.: Contraloría General de la República.

Otto, J. (2006). Mining royalties: A global study of their impact on investors, government, and civil society. World Bank Publications.

Pardo, Á. (2011). Subsidios para la gran minería: dónde están, cuánto nos valen. Colombia Punto Medio. Bogotá D.C. Recuperado a partir de www.colombiapuntomedio.com

Pardo, L. (2013). Propuestas para recuperar la gobernanza del sector minero colombiano. Minería en Colombia, 175.

Rudas, G. (2010). Economía del Níquel. Impuestos, Regalías y condiciones de vida de la ppblación en Montelíbano, Córdoba, Colombia. Sociedad y servicios ecosistémicos, 217.

Rudas, G., & Espitia, J. E. (2013). Participación del Estado y la sociedad en la renta minera. Garay, Luis Jorge (director). La minería en Colombia. Fundamentos para superar el modelo extractivista. Contraloría General de la República. Abril.

Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética - UPME. (2009a). Procesos Mineros en Cerromatoso S.A. Liquidación y Pago de Regalías.

Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética - UPME. (2009b). El Níquel en Colombia.

UPME. (2013). Sistema de Información Minero Colombiano - SIMCO. Precios Internacionales del Níquel (London Metal Exchance - LME).

Vargas, F. (2013). Minería, conflicto armado y despojo de tierras: impactos, desafíos y posibles soluciones jurídicas (Contraloría General de la Nación). Bogotá D.C.

Vicente, A., Martin, N., James, D., Birss, M., Lefebvre, S., & Bauer. (2011). Minería en Colombia: ¿A qué precio? PBI Colombia, Boletín informativo (18), 6.

1.Master in Management Engineering, National University of Colombia at Medellín. Full Time Professor. Institución Universitaria Esumer. E-mail: eduardo.duque@esumer.edu.co

2. Master in Management Engineering, National University of Colombia at Medellín. Senior Professional. Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo Tecnólogico del Sector Eléctrico - CIDET. E-mail: johann.ramirez@cidet.org.co

3. Master in Marketing, University of Manizales. Full Time Professor. Institución Universitaria Esumer. E-mail: juan.restrepo43@esumer.edu.co

4. Master in Public Sector Economics, University of Buenos Aires - Instituto Torcuato Di Tella. Associate Professor, National University of Colombia. E-mail: lvelez@unal.edu.co

5. Cerro Matoso S.A. is the company that owns the Cerro Matoso mine. It is a large mine in the north-west of Colombia in the Córdoba province. Cerro Matoso represents one of the largest nickel reserves in Colombia having great estimated reserves of nickel. The mine's owner is BHP Billiton.

6. These are regions in Colombia. Colombia is politically divided into 32 regions.

8. The Constitutional Court of Colombia (Spanish: Corte Constitucional de Colombia) is part of the Judiciary; it is the final appellate court for matters involving interpretation of the Constitution with the power to determine the constitutionality of laws, acts, and statutes.

9. DIAN is the Colombian Tax and Customs Authority

11. CCC: Colombia's Criminal Code

12. In spanish, its acronym is UPME

13. IFI stands for the Colombian Industrial Reinforcement Institute. Conicol SA stands for Hanna Nickel Company Colombian

14. The CVS works in a timely and appropriate manner for the conservation, protection and management of natural resources and environment for sustainable development of the department of Córdoba.

15. The Colombian Geological Service created to to perform geological mapping, exploration of mineral resources and the study of the Country's subsoil.

16. Misinterpreting the laws and the amendments to the previous Mining Code in 2001 caused this type of situation in the country. Concerning the "foundations", these entities want to evade taxes stating that they support the people to help them overcome poverty and to improve their lives so they can become entrepreneurs. They help to start small businesses that do not represent significant figures to the local economy.

17. The exploitation's gross operating surplus is not really income since it includes the particular benefits before deducting depreciation of assets while rent is net out of such benefits and depreciation. However, in the absence of information on these two variables, for illustrative purposes, it is useful to analyze how such operating surplus between private employer and the State is distributed.

18. Mining does not pay the industry and trade tax to municipalities according to Article 231 of Act 685, 2001. The only direct taxes are not counted here are the property tax and vehicle tax.