HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN

HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN Espacios. Vol. 37 (Nº 35) Año 2016. Pág. 23

Magali Colconi CARRIJO 1; Silvio A. MINCIOTTI 2; José A. MAZZON 3; Leandro C. PREARO 4

Recibido: 29/06/16 • Aprobado: 03/08/2016

ABSTRACT: To explore the influences on the behavior of the buyers, promoted by scenting the internal environments of shops, surveyed in two similar shops. In the first week it recorded the total number of visitors without scenting in shops. The next, one shop was scented and other was not. The behavior of individuals was influenced in scent store, increasing visitation. This attractiveness has not increased in-shop sales, other variables (service, quality etc.) interfered in visitors behavior. There are limitations on the action of scenting environments relevant factor to researchers and managers who have a unilateral view about the influence on behavior when deciding whether to buy. |

RESUMO: Para explorar as influências sobre o comportamento dos compradores, promovidas pela aromatização do ambiente interno das lojas, pesquisou-se em duas lojas similares. Na primeira semana registrou-se o total de visitantes, sem aromatização nas lojas. Na seguinte, uma delas foi aromatizada e outra não. O comportamento dos indivíduos foi influenciado na loja aromatizada, aumentando a visitação. Essa atratividade não aumentou as vendas na loja, outras variáveis (atendimento, qualidade etc.) interferiram no comportamento dos visitantes. Há limitações na ação de aromatizar ambientes, fato relevante para pesquisadores e gestores que dispensam uma visão unilateral das influências sobre o comportamento na decisão de compra. |

At the end of the 20th Century, there was greater publicity of the results of experiments on the effects of scenting of shops. In 2013, Spangenberg confirmed, by researching the effects of scents, that consumers typically spent 31.8% more when an interior decoration shop was scented with a hint of orange. A combination of scents of orange, marjoram and green tea was also tested and, according to this researcher, these scents could have an effect on the cognitive functions of the brain, in the same parts of the brain that are involved in decision-making. He also highlights the importance of the fact that the scents used should fit in well with the shop environment.

In a research study about consumers' reactions in a scented commercial environment, Doucé and Janssens (2013) also noted the adoption of scents by different types of commercial establishments, and here we highlight the following studies: the Westin chain of hotels and resports, that used aromas in its lobbies in order to make the guests more relaxed and relieve stress (PALMER, 2007); the Thomson travel agency, that used a scent of coconut to encourage their clients to bring forward their reservations for the summer holidays (ROBERTS, 2008); the Harrods Department Store in London, England (ROSENTHAL, 2008), and Bloomingdale's in New York, which carried out experiments placing different scents in their respective departments (SMITH, 2009).

Seeking to deepen the studies in this field, the main purpose of this work was to identify and analyze the influence of scents on the internal environment of clothing shops, situated in the city of São Paulo, in Brazil, checking their impact on the behavior of the clients, the number of visitors, and the general results in terms of sales.

Up to the start of the 1970s, the publications on scents addressed their classification, intensity and acceptance, based on the assessments of the individual people researched (HARP, SMITH and LAND, 1968; HENION, 1971). From then on, the scent has taken on a multidisciplinary connotation, with special attention being given to environmental psychology, which intensified the study of primary responses in terms of behavior and emotions, such as excitement, pleasure and dominance (MEHABIAN and RUSSEL, 1974). The information on the perception of the scent as a stimulus also encouraged other such developments in relation to memory, affection and general feelings, such as happiness and sadness, memories, humor (ENGEN, 1982; ERLICHMAN and HALPERN, 1988; HERZ and GAY, 1991; HERZ and CUPCHICK, 1995; MORRIN and RATNESHWAR, 2000; STEVENSON and BOAKES, 2003; WARD and DAVIES KOOJIMAN, 2007; ORTH and BOURRAIN, 2008; CASTELLANOS et al., 2010).

Some authors, who have studies olfative stimuli that have a influence on the behavior of the consumer or buyer, have directed their developments towards the importance of paying attention to the congruence or incongruence of the scent on approval and acknowledgement of the retail environment (MITCHELL, KAHN and KNASCO, 1995). Others, in contrast, value the role of service, the products themselves, and also the brands (MICHON, CHEBAT and TURLEY, 2005; SPANDENBERG et al., 2006; BOSMANS, 2006; SEO et al. 2010).

However, there are very few studies that use commercial establishments in field research (TELLER and DENNIS, 2008). For the analysis of the results of the application of scents to retail environments, there are some publications that have this action as their end target, such as the increase in the time the person spends in the environment. Examples of this positive result have been observed in the scenting of a casino in Las Vegas (HIRSCH, 1995), a sweater shop (KNY, 2006), a restaurant (GUÉGUEN and PETR, 2006; COSTA and FARIAS, 2011); a shop of clothing for young people (MORRINSON et al., 2011). The results of excitement/pleasure and satisfaction/loyalty, arising from the scenting of the environment, have also been tested in coffee shops (WALSH et al., 2011) and at a food retailer (BARBOZA et al., 2012).

With regard to the increase in sales resulting from the decision to scent the shop, the publications have produced conflicting arguments. On the one hand, there are some registers that address the increase that has been observed in the volume of sales (HIRSCH, 1995; CHEBAT and MICHON, 2003; GUÉRGUEN and PETR, 2006; BARBOZA et al. 2010; MORRISON et al., 2011; BARBOZA et al., 2012). On the other hand, there are some arguments that say there is lack of change in sales resulting from the dispersion of scents at points of sale (KNY, 2006; ILLANES and IKEDA, 2009; TELLER and DENNIS, 2012).

Following the line of Environmental Psychology, we find some publications that address the emotional states of pleasure and alertness. These states, in turn, lead to emotional responses such as: a pleasant feeling when buying at the shop; availability to talk to the salespeople; spending more time looking for the shop's special offers; spending more than planned; returning to the shop (BAKER, 1987; BAKER et al., 1992; BITNER, 1992 apud COSTA, 2002).

For the research carried out in this study, a choice was made to follow the model proposed by Mehabian and Russell (1974), which plans to understand the processes of interaction between humans and other variables present in an environment, through the cognitive approach to behavioral theory. These authors said that sensory variables, the quantity of information in the environment, and also individual differences in affective responses, could have an effect on the emotions of these individual people when inside the shop. The variables, in turn, have the capacity of leading them to come closer, or to avoid the environment concerned.

Mehabian and Russell (1974) have used the letter S (stimuli) for all sensory variables that are present in the atmosphere, such as light, scents and smells, and temperature, among others. These sensory variables could have an influence on the intentions and orientation of the individual, and the authors have identified these by the letter “R” (responses). There is also the letter "O" (organism), which corresponds to the generation of a greater or lesser emotional state in the individual. This means there is a structure based on “stimulus-organism-response” (S-O-R), the model known as “Stimulus-Organism-Response” (S-O-R) as proposed by Mehabian and Russell (1974). For them, an individual ("O") becomes subject to external stimuli (“S”) and reacts emotionally to these. These emotions are classified as follows: Pleasure-Displeasure (P); Activation-Deactivation (A) and Dominance-Submission (D). These three classifications are known as the "P-A-D" Structure (RUSSELL and MEHABIAN, 1976; MIHABIAN, 1977; MEHABIAN, 1997).

The most common consumer behavior patterns are intermediated by these three responses, such as the desire to come closer to the environment, the desire to leave, the wish to spend money and consume (Mehrabian, 1979; Mehrabian and Riccioni, 1986; Mehrabian and de Wetter, 1987; Mehrabian and Russell, 1975; Donovan and Rossiter, 1982; Russell and Mehrabian, 1976, 1978 apud Foxwall, 1997).

Based on the model proposed by Mehabian and Russell (1974), a scent was used as the stimulus ("S"), spread throughout the internal environment of a point of sale, whose main aim was to check the influence thereof on the behavior shown by the visitors to the shop ("O"), who showed positive or negative responses ("R").

For the field research, use was made of the quasi-experimental method because, according to Selltiz, Wrigjtsman and Cook (1987, p. 2), this could explain the relations between cause and effect.

In this study, the independent variable was characterized by the presence of a scent, and the dependent variable was the resulting factor (number of visitors and sales). For Selltiz, Wrigjtsman and Cook (1987, p. 21), the independent variables are the causes and the dependent variables are the effects.

In observing causes and effects, there was the use of a well-known delineation as pre-experimental, and here there was the confirmation of plausible hypotheses that could explain possible differences such as, for example, in the behavior of the group of people that was observed. These differences were obtained in a comparative manner, between the results that were recorded in a pre-test and those recorded in post-test. In this kind of delineation, the following variants were used:

As results of these variables, we have two distinct groups, known as the control group (O) and the experimental group (X).

Seeking to ensure the similarity between the shops analyzed, the field research occurred inside two clothing shops, of a same franchisor, which has been present in the subsector of children's wear since 1988, both with the same owner. The field study was carried out between 2 and 15 May 2014.

These shops are situated in two different Shopping Centers which also show similar characteristics, being located in the same urban zone of São Paulo, that have provided information about volumes of sales, the scent used for the scenting of the environments, and access to the visitors to take part in the survey.

A company from the scenting sector has also been selected, thus making available for the research three units of electronic equipment for automatic scenting, the packing of the scents in special sprays, the assistants and technicians for installation, and also the checking of the equipment used.

For the collection of data, use was made of the instruments known as Register of Visits (to record the number of visitors to both shops) and Structured Individual Interview Form (to note the answers of the visitors who were interviewed).

For the quasi-experiment, the following two groups were formed:

- 1st Week – registration of visitors - Shopping Morumbi (O1) and Eldorado (O3)

The number of visitors who entered the shops was recorded, as also the total of tax invoices issued per day.

- 2nd Week – registration and interviews of visitors - Shopping Morumbi (O2)

The number of visitors who entered the shops was recorded, as also the total of tax invoices issued per day. At the same time, some visitors were interviewed inside the shop.

- 1st and 2nd Weeks – recording and interview of visitors

Defined as the experimental group, the shop at the Eldorado shopping centre (O4) was scented, and the differences in the behavior patterns of the buyers after the scenting were recorded (X). The number of visitors was noted down and also the total volume of tax invoices issued per day. At the same time, some visitors were interviewed inside the shop, using a sampling procedure for convenience.

It was also decided to choose the promotional date of “Mother's Day” in order to ensure a relevant number of people for the sample used in the survey.

The field research study was conducted between 2 and 15 May 2014, and the date was collected as follows:

After the classification of the variables and normality testing, we checked the relationships between the variables studied. Initially, the statistical tests performed were the t test (comparison between two groups) and analysis of variance (ANOVA), comparing the variances. This analysis also had the GLM (General Linear Model) and the procedures of analysis of GZLM models (Generalized Linear Models), to compare variances, and the Mann-Whitney test to compare medians.

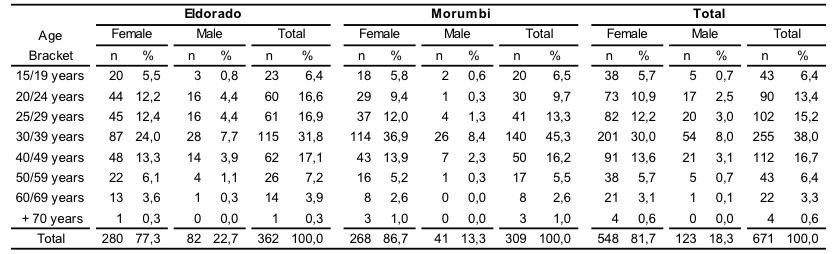

The composition of the sample by gender is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 – Gender of the people interviewed – shops at Eldorado and Morumbi shopping centers

Source: Data of the survey

According to Critério Brasil, the results regarding the social classes of the visitors interviewed are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 – Social Class of the visitors interviewed (Critério Brasil)

Eldorado and Morumbi Shopping Centers

Source: Data of the survey

As we can see from Table 2, we have the following results, regarding the three first places occupied:

The results shown in Table 2 show that the Morumbi shop has more visitors from the more affluent “A” social group, while the shop at the Eldorado shopping centre has more visitors from Class "B".

In relation to the total number of visitors, we have the following first hypothesis formed:

H1. The variation in the number of visitors of two similar shops is influenced by the scenting of one of them.

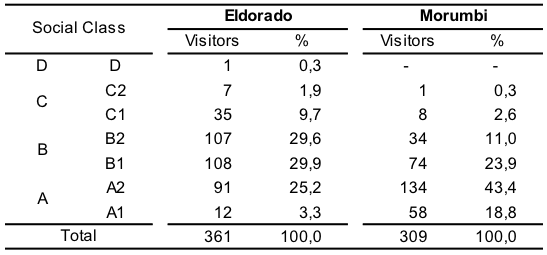

Based on the daily results regarding the number of visitors that enter the shops at the Morumbi and the Eldorado shopping centers, during the period of two weeks, which means between 2 and 8/5 and between 9 and 15/5/12, Table 3 that follows was drawn up, showing the results below.

Table 3 – Total Visitors per Day shops in the Eldorado (O3 – no scent and O4 – scented)

and Morumbi (O1 and O2 – no scent) shopping centers - 2 to 15/5/2014

Source: Data of the survey

In Table 3, the total number of visitors at the Morumbi shop (O1), between 2 and 8 May 2014, was 29% higher than in the Eldorado shop (O3). Between 9 and 15 May, the period in which the Eldorado shop (O4) had the presence of scent, we saw that the difference in the results in favor of the Morumbi shop (O2) practically disappeared, when compared with the Eldorado shop (O4), as this shop was now 2% better than at the Morumbi shop (O2).

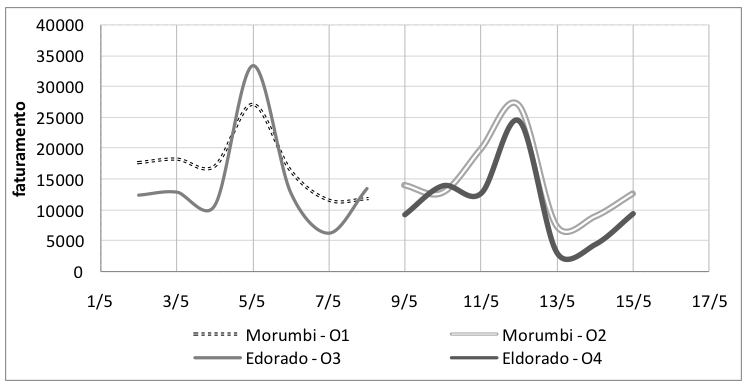

In this period when the scent was applied, we also highlight that fact that on four of the days considered (11/5, 12/5, 13/5 and 14/5), the Eldorado shop (O4) welcomed more visitors than the Morumbi shop (O2), as we can see in Graph 1.

Graph 1 – Variation in the total number of visitors to the shops at the Eldorado and Morumbi shopping centers - from 2 to 15/5/2014

Source: Data of the survey

In general, through Graph 1, we can see that, in the first week (between 2 and 8 May 2014), there was a higher number of visitors, when compared to the second week (between 9 and 15 May 2014), this being a phenomenon visible both in the Eldorado shop as in that of Morumbi.

However, in relation to the second week, we see that the reduction in the number of visitors to the Eldorado shop was proportionally less than in the Morumbi shop. This fact can be justified due to the fact that the Eldorado shop (O4) was scented in the second week (9 to 15/5/12), from which one can infer a certain influence on the behavior pattern of visiting the shop, when compared to the Morumbi shop (O2), in this same period.

Going deeper into these comments, a comparison was made between the results for the Eldorado shop (O3/without scent and O4/scented), experimental group, compared with the results for the Morumbi shop (O1 and O2, both without scent), control group, analyzing the proportion of variance of the number of visitors between the days of these weeks observed.

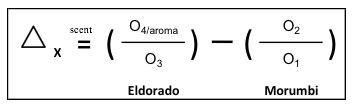

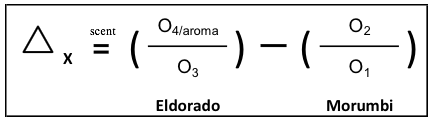

This proposal can be represented as follows:

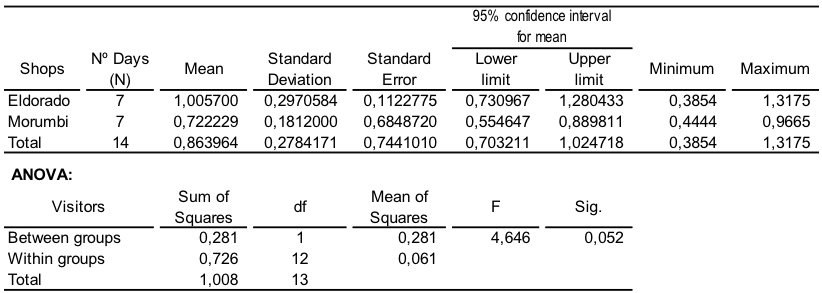

Next, we have Table 4, which shows the statistical results related to this proposal.

Table 4 – Variation of the proportion of the number of visitors, as a result of use of scents – same shop:

Eldorado (O4 - scented)/Eldorado (O3 – without scent) and Morumbi (O2 – without scent) /Morumbi (O1 – without scent) - Periods of 2 to 8 May and 9 to 15 May 2014

Source: Data of the survey

Comparing the statistical results between the experimental groups (Eldorado shop: O3 – without scent and O4 – with scent) and control groups (Morumbi shop: O1 and O2 – both without scent), one can see that there has been a relevant difference in the variation of the quantities of visitors (at a significance level of 10%) between the two weeks that were surveyed. This can be proved through the results of the statistical tests (Example: Sig. ANOVA = 0.052; where the expected result was Sig.<0.10).

Interpreting these results as obtained, we have the non-rejection of "H1", as statistical tests show that the variation of the number of visitors in the Eldorado shop when scented (O4) and without scent (O3) was higher than the variation in the number of people observed in the Morumbi shop (O1 and O2 – without scent) in the two periods analyzed. The scent factor in the Eldorado shop has provided the smallest variation in the number of visitors, in the periods as analyzed, when compared with the Morumbi shop.

To check if there has been any influence of the scenting of the Eldorado shop on the effective sales results, there was an analysis of total turnover, through data supplied by the managers of the shops.

Considering the data about turnover, we have the second possibility developed: H2. The variation in turnover of two similar shops is influenced by the scenting of one of them.

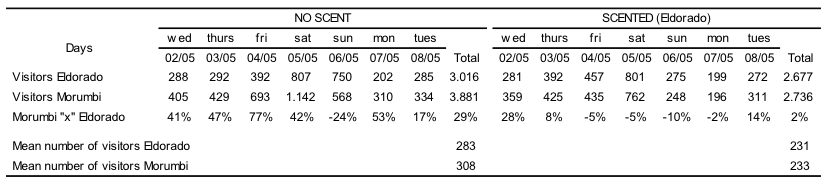

To show the general income performance of the Eldorado shop (O3/without scent and O4/with scent) and Morumbi (O1 and O2 – without scent) in the two weeks, Graph 2 was prepared.

Graph 2 – Turnover of Eldorado shop (O3/without scent and O4/with scent)

and Morumbi shop (O3/without scent and O4/with scent) – period between 2 and 15 May

Source: Data of the survey

Looking at these results, we see that, between 2 and 8/5, the variation seen in the Eldorado Shop (O3 – without scent) exceeded the invoiced turnover of the Morumbi shop (O1 – without scent) on 5 and 8/5. Between 9 and 15/5, the scented Eldorado shop (O4) surpassed the invoiced turnover of the Morumbi shop (O2 – without scent) only on 10/5.

Hence, our conclusion is that the scenting of the environment did not seem significant, when it comes to the increase in turnover that has been observed.

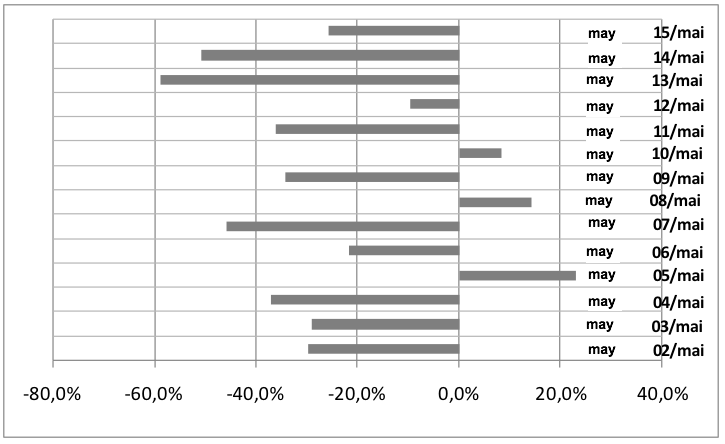

In a move to prove the results shown regarding percentage variation of turnover, as observed between the Eldorado (O3/without scent and O4/scented) and Morumbi shops (O1 and O2 – without scent), between 2 and 15/5/2014, we have obtained Graph 3.

Graph 3 – Percentage Variation in Turnover:

Eldorado Shop (O3/without scent and O4/with scent) when compared to Morumbi (O1 and O2 – without scent) – period from 2 to 15/05/2014

Source: Data of the survey

Going deeper into this issue, a comparison was made between the records of the Eldorado shop (O3/without scent and O4/with scent), experimental group, when compared to those of the control group at the Morumbi shop (O1 and O2, both without scent), control group, analyzing the proportion of variation of turnover on the days of these weeks as observed.

This proposal can be represented as follows:

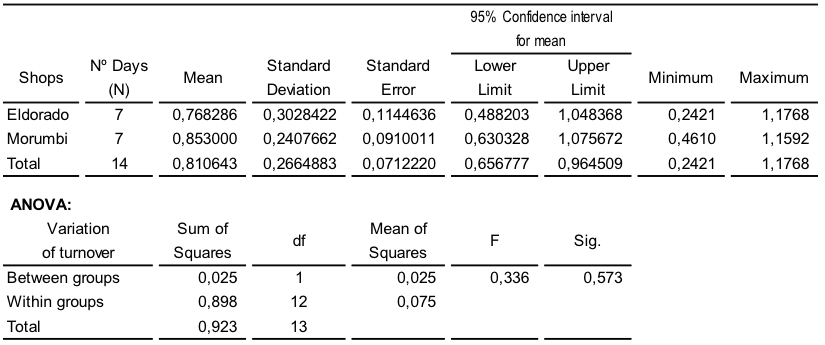

Next, Table 5 shows the statistical results related to this proposal.

Table 5 – Variation of Turnover resulting from scenting – same shop: Eldorado (O4 – with scent) /Eldorado (O3 – without scent)

and Morumbi (O2 – without scent) / Morumbi (O1- without scent) – from 2 to 8/5 and from 9 to 15/5/12

Source: Data of the Survey

Comparing the Eldorado shop (O3/without scent and O4/with scent), the experimental group, with the Morumbi shop (O1 and O2, both without scent), which is the control group, i Table 5 that follows we can see that the difference in the variation of turnover has not been relevant (at a significance level of 10%) between the two periods surveyed. This can be confirmed by means of the results of the statistical tests (example: Sig. = 0.573; where the expected value was Sig.<0.10).

Interpreting these results, we have a rejection of "H2", as the statistical tests show that the proportion of the variation of turnover between the Eldorado shop when scented (O4) and unscented (O3) was less than the variation in turnover observed between the Morumbi shop in the two periods analyzed (O1 and O2 – both without scent). The scent factor within the scope of the Eldorado shop seems not to have caused a significant variation in turnover, when compared to the variation which occurred at the Morumbi shop, without scent, between the periods that have been analyzed here.

The results obtained between hypotheses "H1" (the scent of the environment of a shop increases the number of visitors) and "H2" (the scent of the environment of a shop does not increase turnover) seem to be contradictory when analyzed based on logic.

In the light of this fact, new analyses were made in order to get to know the variables that could have had a bearing on these results and, among these, there was a deeper consideration of the data related specifically to the buyers.

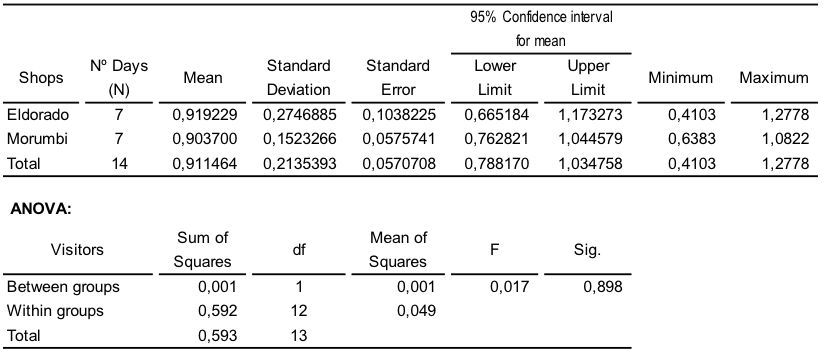

Firstly, there was the consideration of the variation in the number of buyers and, for this purpose, a comparison was made between the Eldorado shop with scent (O4) and the Morumbi shop without scent (O2), between 9 and 15/5, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6 – Variation in the number of buyers – similar shop: Eldorado (O4 – with scent)

versus Morumbi Shop (O2 – without scent) – period between 9 and 15/05/12

Source: Data of the Survey

In Table 6, we see that the variation in the number of buyers in the case of the Eldorado shop with scent (O4) was not relevant, and in fact was less than that of the Morumbi shop without scent (O2), considering a level of significance of 10%. This can be checked through the results of statistical tests (example: Sig. = 0.898; where the expected result was that of Sig.<0,10).

In new statistical tests, we considered the variation in the proportion of buyers considering the total number of visitors. For this, a comparison was made between the Eldorado shop with scent (O4) with the Morumbi shop without scent (O2), in the period between 9 and 15/5.

Comparing the Eldorado shop with scent (O4) and the Morumbi shop without scent (O2), we see that there has been a relevant difference in the variation of the proportion of the number of buyers in relation to the total number of visitors (at the significance level of 10%). This can be confirmed by means of the results of the statistical tests (example: Sig. = 0.002; where the result expected was Sig.<0,10).

These statistical results can also be seen in Graph 6. Interpreting the results obtained, we see that the proportion of the variation of the number of buyers, in relation to the proportion of variation in the number of visitors, was smaller in the Eldorado shop with scent (O4) in relation to that observed in the Morumbi shop without scent (O2).

Initially, one could imagine that the presence of the scent in the environment caused this proportional reduction among buyers versus visitors, a phenomenon that has been observed in both the Eldorado and Morumbi shops.

However, a deepening of the discussion of this issue has led to the need for additional statistical tests (General Linear Model - GLM), for a better understanding of the behavior of these buyers, seeking possible factors that intervene in their respective decisions.

For this purpose, we have considered the correlation that exists between some data of the buyers (gender, age and social class), in relation to the respective appraisals that they have made with regard to variables such as service, quality, price, environment, time frame, type of product and special promotions.

In the multivariate tests that have been performed, on comparing the Eldorado shop duly scented (O4) with the Morumbi shop without scent (O2), we see that statistical tests suggest differences in the seven variables that have been assessed by different buyers, observing the following:

In the light of these results, we see that other variables have probably had an influence on the decision to buy products, taken by visitors to the shops in the Eldorado and Morumbi shopping centers, making it possible for there to be an influence on the behavior of these individuals. Among these factors, we highlight the service and the quality of the products, items that are quite relevant when they are related to the key variables of age and social class, for the visitors to these shops.

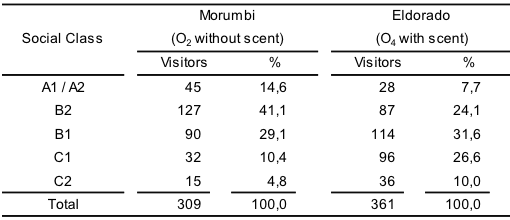

With regard specifically to social class, other statistical tests were also performed (ANOVA), seeking to expand knowledge about this issue. For this purpose, a new grouping was established between the registered frequencies of the social classes of the visitors of the shops in the Eldorado (O4 – with scent) and Morumbi (O2 – without scent), in the period between 9 and 15/5, results which are shown in Table 8 that follows.

Table 8 – Grouping of social classes – shops in the Eldorado Shopping Centre (O4 – with scent)

and Morumbi Shopping Centre (O2 – without scent) – period between 9 and 15/5

Source: Data of the Survey

In Table 8, we see a greater concentration of visitors in the more affluent social classes (A1, A2 and B1) in the Morumbi shop (O2 – without scent), accounting for 55.7% of the total. This result is different from that of the Eldorado shop (O4 – with scent), which had more people from the B1 and C1 social classes, accounting for 58.3% of the visitors.

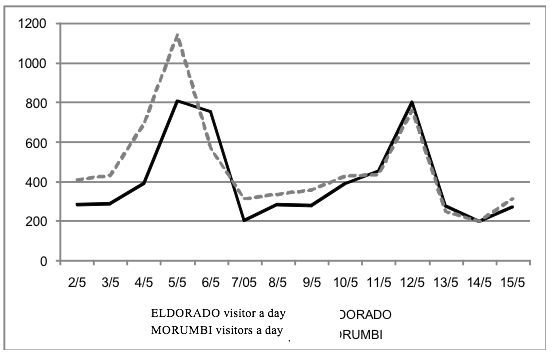

Together with these results for social classes, there was also a comparison with the opinions of these visitors about the shops at the Eldorado (O4 – with scent) and Morumbi (O2 - without scent) shopping centers, with regard to service, quality, time frame, environment, price, type of product and special promotions. Here, it is worth pointing out that the appraisal of these seven variables has been made through a point scale ranging from zero (no influence whatsoever) to ten (total influence), thus allowing the identification of which of these factors had “more” and “less” influence on the decision to make a purchase, at the shops analyzed in this study.

Through the results of the statistical tests, we can see that the visitors to the Morumbi shop (O2 – without scent) have given a positive assessment to the variables shown, that could have an influence on their decision to make a purchase (service, quality, time frame, environment, price, type of product, and special promotions), as the means of the scores recorded lie between a maximum of 9.43 (quality) and 6.86 points (time frame). On the other hand, the visitors to the Eldorado shop (O4 – with scent) have a less favorable opinion about the seven respective variables that could affect the decision to buy, as the means of the scores supplies range from a minimum of 2.52 (promotions) to a maximum of 5.33 (type of product).

This result has been confirmed in the ANOVA test, showing that, at a level of significance of 10%, the "Sig" results were less, where a value of "Sig.<0,10" was expected for the appraisal of service, quality, time frame, environment, price, type of product, and special offers.

A comparison was also made between the means of the scores supplied by visitors to the Eldorado shop (O4 – with scent) and the Morumbi shop (O2 – without scent), with a view to analyzing the appraisal of each one of these seven variables as mentioned, respectively.

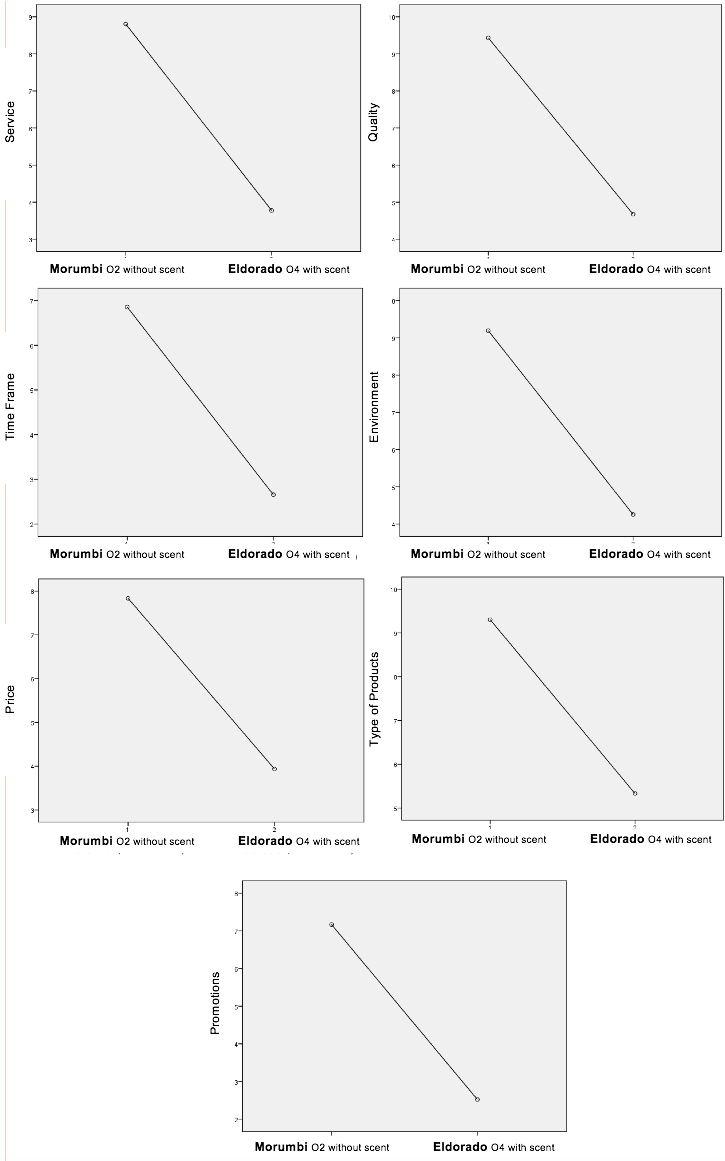

These representations are grouped in sequence, and shown in Graph 4.

Graph 4 – Average point scores given by visitors to the Eldorado shop (O4 – with scent)

and Morumbi shop (O2 – without scent), regarding the variables: service, quality, time frame, environment,

price, type of product and special promotions – from 9 to 15/5/12

Graph 7 shows us that the average point scores supplied by the visitors to the Eldorado shop are lower than all the scores informed by the visitors to the Morumbi shop, for all the characteristics analyzed, which are service, quality, time frame, environment, price, type of product, and special promotions, in the period from 9 to 15/5/2014. Therefore, these seven variables have had a greater influence upon the visitors to the Morumbi shop (O2 – without scent) than upon those to the Eldorado shop (O4 – with scent).

Therefore, we see that the variables presented have indeed affected the visitors of the Eldorado (O4 – with scent) and Morumbi (O2 – without scent) shops, having an influence on their decision to buy.

This is a relevant point in this study, as this could justify the disagreeing results that were obtained, with an apparent contradiction between hypotheses "H1" (a scent within a shop increases the number of visitors), as shown in item "4.4.3.1 Quantity of Visitors”, and “H2” (the scent inside a shop does not increase its turnover).

The results shown in this research study show that the dispersion of a scent in a shop's internal environment does indeed help to attract new visitors to a clothing shop within a shopping centre. This attraction has been proven by the increase in the number of registered visitors, when a comparison was made between similar establishments of one same franchise.

In the two periods analyzed, the shop that did not receive any scent, which often has a larger number of people visiting it, showed a fall in the variation of the number of visitors. This reduction of people should also be observed in the shop with an aroma. However, in the second week, when the shop had scent, this did not happen, with the number of visitors to the location remaining constant.

These results match the findings contained in the model as proposed by Mehabian and Russell (1974), as the scent that is scattered throughout the shop has caused stimuli and generated approximation. These positive responses were also confirmed by other authors, such as BONE and JANTRANIA, 1992; HIRCH, 1995; KNASCO, 1995; MITCHELL et al., 1995; SPANGENBERG et al., 1996; MORRIN and RATNESHWAR, 2000; MATTILA and WIRTZ, 2001; CHEBAT e MICHON, 2003; MICHON et al., 2005; ORTH e BOURRAIN, 2005; and GUÉGUEN and PETR, 2006.

However, for the scent scattered around the environment to have a positive influence on the behavior of individuals, allowing an increase in the number of visitors, there should be an observance of the congruence between the scent and the type of shop, the product or service made available, and the profile of the visitors, among other considerations (JANTRANIA, 1992; MITCHELL, KAHN and KNASCO, 1995; SPANGENBERG et al., 1996).

At the same time, the opinions of the visitors themselves about the scent are also essential, as they can provide the perception about the general atmosphere of the shop (CHEBAT, MICHON, 2003).

Another fact to be considered is that this attractiveness of visitors, promoted by the act of scenting the shops, does not in itself guarantee that the people shall make a decision to buy. This argument is confirmed through the results registered with regard to sales made at the two shops analyzed.

The assessment between shops with and without scent has shown irrelevant results, in the two weeks during which sales have been analyzed. Therefore, the variation in turnover has not been influenced by scenting of the environment, when similar shops are compared.

Other variables have interfered in the decisions regarding purchases, made by the Eldorado and Morumbi shops, making possible the influence on the behavior of these individuals. Among these factors, we mention the service provided and the quality of the products, which are relevant items when related to the variables of age and social class of the visitors to these shops.

In possession of these results, we could make some final comments. In the shops analyzed, the Eldorado shop has less visitors than Morumbi. To this result, we add the fact that the social class of the visitors to the Morumbi shop includes more people from the affluent “A” class than the Eldorado.

Closing these considerations, we see that the scent scattered around the shop environment has an influence in people's behavior, providing an atmosphere that can provide greater satisfaction (pleasure) to the visitors.

Looking at the scent factor taken in isolation, we cannot say that it has an influence on the act of making a purchase, as there is no evidence of any significant variations to turnover.

For there to be an actual increase in sales, apart from efficient and effective management of the marketing side, one must also be aware of all the other variables that are inserted in the atmosphere of the shop, including the quality of the service, as well as those related to the human senses that bring stimuli.

Astous, A. d'., 2000. Irritating Aspects of the Shopping Environment. Journal of Business Research 49, 149–156.

Baker, J., 1987. The role of environment in marketing services: the consumer perspective. In: The Services Marketing Challenge: Integrated for Competitive Advantage, 1987. Proceedings. American Marketing Association, 79-84.

Baker, J.; Grewal, D.; Lvy, M., 1992. An experimental approach to making retail store environment decisions. Journal of Retailing 68, 445-460.

Barbosa Jr., F.; Carneiro, J. V. C.; Arruda, D. M. O.; Rolim, F. M. C., 2010. Estímulos olfativos influenciam decisões de compra? Um experimento em varejo de alimentos. Revista Alcance - Eletrônica 17/1, 58-72 (January-March).

Barbosa Jr., F.; Quezado, I.; Arruda, D. M. O.; Moura, H. J., 2012. O aroma de chocolate como estímulo de aproximação e afastamento do consumidor no ambiente de varejo alimentício. Gestão Contemporânea 9/12, 181-205 (July-December).

Bitner, M. J., 1992. Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing 56, 57-71.

Bone, P. F., Jantrania, S., 1992. Olfaction as a cue for product quality.Marketing Letters 3/3, 289-296 (July).

Bosmans, A., 2006. Scents and sensibility: When do (in)congruent ambient scents influence product evaluations? Journal of Marketing 70, 32-43.

Campbell, D. T.; Stanley, J. C., 1979. Delineamentos experimentais e quase-experimentais de pesquisa. São Paulo: EPU – Editora da Universidade de São Paulo.

Castellanos, K. M.; Hudson, J. A., Haviland, J., Wilson, P. J., 2010. Does exposure to ambient odors influence the emotional content of memories? TheAmerican Journal of Psychology. Fallv 123/3, 269-79.

Chebat, J; Michon, R., 2003. Impact of ambient odors on mall shoppers’ emotions, cognition, and spending. A test of competitive causal theories. Journal of Business Research 56/7, 529-539.

Costa, A. L. C. N.; Farias, S. L., 2011. O aroma ambiental e sua relação com as avaliações e intenções do consumidor no varejo. RAE - Revista de Administração de Empresas. São Paulo 51/6, (November/December), 528-541.

Donovan, R. J., Rossiter, J. R., 1982. Store atmosphere: an environmental psychology approach. Journal of Retailing 58/1 (Spring), 34-57.

Doucé, L.; Janssens, W., 2013. The Presence of aPleasant AmbientScent in a Fashion Store: The Moderating Role of Shopping Motivation and Affect Intensity. Environment and Behavior 45/2, 215–238.

Ehrlichman, H.; Halpern, J. N., 1988. Affect and memory: Effects of pleasant and unpleasant odors on retrieval of happy and unhappy memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55, 769-779.

Engen, T., 1982. The Perception of Odors. New York: Academic Press.

Foxwall, G. R., 1997. The emotional texture of consumer environments: A systematic approach to atmospherics. Journal of Economic Psychology 18, 505-523.

Guéguen, N.; Petr. C., 2006. Odors and consumer behavior in a restaurant. Hospitality Management 25, 335–339.

Harper, R.; Smith, E. C.; Land, D. G., 1968. Odour description and odour classification: A multidisciplinary examination. Oxford, England: American Elsevier.

Henion, K. E., 1971. Odor Pleasantness and Intensity: A Single Dimension. Journal of Experimental Psychology 90/3, 275–279.

Herz, R. S., Gay, S. E., 1991. The Effect of Ambient Olfactory Stimuli on the Evaluation of a Common Consumer Product. Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Association for Chemoreception Sciencesn (April).

Herz, R.; Cupchick, G. C.; 1995. The Emotional Distinctiveness of Odor-Evoked Memories: Chemical Senses 20, 517-528.

Hirsch, A. R., 1995. Effects of ambient odors on slot-machine usage in a Las Vegas casino. Psychology and Marketing 12, 585-594.

Illanes, M. A. T.; Ikeda, A. A., 2009. O estímulo olfativo como ferramenta de marketing no varejo. XII SEMEAD - Seminários em Administração. Programa de Pós-graduação em Administração da FEA-USP (27/28 August).

Knasco, S. C., 1995. Pleasant odors and congruency: Effects on approach behavior. Chemical Senses 20, 479–487.

Kny, M. A., 2006. Impacto de aromas ambientais sobre o comportamento do consumidor no varejo. Dissertação (Mestrado em Administração), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

Matilla, A. S., Wirtz, J., 2001. Congruency of scent and music as a driver of in-store evaluations and behavior. Journal of Retailing 77, 273–289.

Mattar, F. N., 2005.Pesquisa de Marketing: metodologia e planejamento. São Paulo: Atlas.

Mcdaniel, C. D.; Gates, R., 2005. Fundamentos de Pesquisa em Marketing. Rio de Janeiro: LTC.

Mehrabian, A.; Russel, J.A., 1974. An Approach to Environmental Psychology. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Mehrabian, A., 1976. The three dimensions of emotional reaction. Psychology Today, 10/3, 57-61.

Mehrabian, A., 1977. Individual differences in stimulus screening and arousability. Journal of Personality 45, 237-250.

Mehrabian, A., 1997. Analysis of affiliation-related traits in terms of the PAD Temperament Model. Journal of Psychology 131, 101-117.

Mehrabian, A., Riccioni, M., 1986. Measures of eating-related characteristics for the general population: Relationships with temperament. Journal of Personality Assessment, 50, 610-629.

Mehrabian, A., de Wetter, R. (1987). Experimental test of an emotion-based approach to fitting brand names to products. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 125-130.

Michon, R., Chebat, J-C, Turley, L. W., 2005. Mall atmospherics: the interaction effects of the mall environment on shopping behavior.Journal of Business Research 58/5, 576-583.

Mitchell, D. J., Kahn, B. E., Knasco, S. C., 1995. There’s Something in the Air: Effects of Congruent or Incongruent Ambient Odor on Consumer Decision-Making. Journal of Consumer Research 22/2, 229–238.

Morrin, M.; Ratneshwar, S., 2000. The Impact of Ambient Scent on Evaluation, Attention, and Memory for Familiar and Unfamiliar Brands. Journal of Business Research 49, 157–165.

Morrison, M., Gan, S., Dubelaar, C., Oppewal, H., 2011. In-store music and aroma influences on shopper behavior and satisfaction. Journal of Business Research 64, 558–564.

Orth, U. R., Bourrain, A., 2008. The influence of nostalgic memories on consumer exploratory tendencies: Echoes from scents past. Journal of Retailing and Consumer services 15, 277-287.

Orth, U. R., Bourrain, A., 2005. Ambient Scent and Wine Consumer Exploratory Behavior: A Causal Analysis. Journal of Wine Research 16/2, 137-150.

Palmer, K., 2008. The Scent of higher volume. U.S. New & World Report, 55-56 (October 29).

Roberts, J., 2008. On the scent trail. Brand Strategy, 14-15 (February).

Rosentrhal, J., 2008. Led by the nose. Economist, 132-134 (December 20).

Russell, J.A., Mehrabian, A., 1976. Environmental variables in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research 3, 62-63.

Russell, J.A., Mehrabian, A., 1978. Approach-avoidance and affiliation as functions of the emotion eliciting quality of an environment. Environment and Behaviour 10, 355-387.

Selltiz, C.; Wrightsman, L.; Cook, S.; Kidder, L., 1987. Métodos de Pesquisa nas Relações Sociais. São Paulo, EPU – Editora Pedagógica e Universitária.

SEO, H. S.; ROIDL, E.; MÜLLER, F. NEGOIAS, S., 2010. Odors enhance visual attention to congruent objects.Appetite 54/3, 544-549, (June).

Smith, S., 2009. Scents and sell ability. Stores Magazine, 42-43 (July).

Spangenberg, E., Crowley, A., Henderson, P., 1996. Improving the Store Environment: do olfactory cues affect evaluations and behaviors? Journal of Marketing 60/2, 67-80.

Spangenberg, E., Sprott, D. E., Grohmann, B., Tracy, D. L., 2006. Gender-congruent ambient scent influences on approach and avoidance behaviors in a retail store. Journal of Business Research 59, 1281-1287.

Spangenberg, E., Sprott, D. E., Zidansek, M.; Herrmann, A., 2013. The Power of Simplicity: Processing Fluency and the Effects of Olfactory Cues on Retail Sales. Journal of Retailing 89/1, 30-43 (March).

Stevenson, R., J., Boakes, R. A., 2003. A Mnemonic Theory of Odor Perception. Psychological Review 110/2, 340–364.

Teller, C.; Dennis, C., 2012. The effect of ambient scent on consumers’ perception, emotions, and behavior: A critical review. Journal of Marketing Management 28/1–2, 14-36 (February).

Turley, L. W., Milliman, R. E., 2000. Atmospheric Effects on Shopping Behaviour: A review of the Experimental Evidence. Journal of Business Research 49/2, 193-211.

Walsh, G., Shiu, E., Hassan, L. M., Michaelidou, N., Beatty, S. E., 2011. Emotions, store-environmental cues, store-choice criteria, and marketing outcomes. Journal of Business Research 64, 737–744.

Ward P., Davies, B. J., Koojiman, D., 2003. Ambient smell and the retail environment: Relating olfaction research to consumer behavior. Journal of Business and Management 9, 289-302.

1. Doctor, Universidade Municipal de São Caetano do Sul, BR. Email: m.colconi@gmail.com

2. Doctor, Universidade Municipal de São Caetano do Sul, BR

3. phD, Universidade de São Paulo/FEA, BR

4. Doctor, Universidade Municipal de São Caetano do Sul, BR