HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN

HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN Espacios. Vol. 37 (Nº 37) Año 2016. Pág. 23

Renata POSTAL 1; Héder Carlos DE OLIVEIRA 2

Recibido: 15/07/16 • Aprobado: 02/08/2016

ABSTRACT: The study of economic resilience has grown in importance due to the latest global crisis. The present paper is an attempt to measure the performance of the countries on maintaining its GDP growth during the outcomes of the last financial crisis, which means how resilient they were. To access it, a panel data analysis is conducted, where the information of 78 countries, from 2007 to 2014, is evaluated. In the findings, among all the variables employed, it is stated that institutions, life expectancy and infrastructure are significant factors on understanding the behavior of the economies when dealing with the financial stress of 2008. |

RESUMO: O estudo da resiliência econômica tem apresentado grande importância devido à última crise econômica. O presente artigo tem como objetivo medir o desempenho dos países em relação ao crescimento do PIB durante a crise de 2008, ou seja, verificar o quão resilientes os países são. Para isso, foi utilizado econometria de Dados em Painel, para 78 países, no período de 2007 a 2014. Os resultados indicam que, dentre as variáveis de controle, instituições, expectativa de vida e infraestrutura são fatores significantes para entender o comportamento do PIB dos países diante os impactos da crise financeira de 2008. |

The economy, mainly in the capitalist system, is made by cycles. Over the history, the booms and busts faced by countries have called the attention of academics, who have tried to predict certain patterns and understand the economical behavior. Would the great depression of 1929 have the same effect if the presence of the government in the economy was greater? Was it possible to prolong the effects of the baby boomer generation? Could the mortgage bubble which started in the United States and resulted in the recent global financial crisis be avoided? While several questions stay open for discussion, history shows that economies will eventually face a downturn, but the fact is that the depth of the consequences will depend on their ability to respond to these shocks, or, how resilient they can be.

Although there is no agreement on a single definition, economic resilience is described by the OECD (2014) as the ability of households, communities and nations to absorb and recovery from shocks. Commonly, the literature also make use of two broad definitions, engineering resilience, which is the resistance of a system to shocks and the speed of recovery to its pre-shock state, and ecological resilience, which focuses on the role of a shock on pushing a system beyond its “elasticity threshold” to a new domain, or the magnitude of a shock that can be absorbed before the system changes its form.As there is no static classification, in the present paper economic resilience is interpreted as the ability of the countries to keep its growth figure, despite being hit by a shock. In this way, there is an approach towards the engineering resilience.

Similarly, the impact of certain variables on the resilience skills of a country or region is still an open topic for the literature. As it will be seen, when econometric models are applied, the choice of the dependent variable is usually given between GDP growth and unemployment rate, but the scenario is different for the selection of the independent variables. Proxies for education, health conditions, income, level of development and banks exposure, among others, are used in the construction of the models, nevertheless the choice of the factors vary from research to research, and from which shock is being studied, as they may reach different sectors of the economy.If in one way this fact makes it difficult to delimit what is really essential on understanding resilience, it also encourages the research on the topic, as relevant contributions can still be make.

As pictured, the study of economic resilience requires the analysis of a shock. This paper proposes at analyzing the effect of the last financial crisis, due to its intensity, broadness and recent consequences. Starting as a subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, the financial bust of 2008 soon escalated and became a global economic meltdown. The underestimation of the stress, highlighted by the constant adjustments downwards on growth forecasts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank during 2008 and 2009, only increased the effects of it. Although countries with a developed financial sector were the ones to feel the crisis first, the literature suggests that the drop in international trade and in the work remittances contributed to spread the impact.

Seeking to add insights to the literature, this paper has two goals. First, it aims at specifically analyzing the importance of institutions on the economic resilience during the last financial crisis. This variable is considered important because it allows governments to take accurate measures and to elaborate the necessary public policies during delicate moments. Contrary to expectations, the role of institutions on the resilient process has not been widely explored in the literature, which raises the importance of the current study. Second, this paper tries to identify which other variables may be important to understand the response of the countries to the last financial crisis. As each shock has its peculiarities, meaning that the influence of a given variable on economic resilience is likely to vary due to the origin of the distress, a close look at the financial crisis seems to be necessary to correctly interpret the resilience process.

In order to reach its goals, this paper is organized as follows. In the first section, a literature review will be presented, in which the main lines of thought about economic resilience are introduced, as well as the common variables used to study the phenomenon. Concomitant, the last financial crisis will be explained, as this event allowed testing the ability of the countries to rebound an economic downturn. The second section is devoted to explain the methodology used and the data collected. On the third section, the estimation of the model and results found during the research will be presented. Lastly, the conclusions will be stated and some possible extensions will be suggested.

Reducing the impact of crisis and learning how to better deal with disadvantaged events are prior goals of governments. With the increasing of global interconnectivity, the study of economic resilience has gained attention in the agenda and has played an important role on understanding the degree to which a country is hit by a downturn. The correct interpretation of the factors involved in this process can also help the countries on building capabilities and, therefore, become less likely to suffer from future events.

Hill, Wial and Wolman (2008) state that four broad themes are associated with the concept of resilience: equilibrium, path dependency, systems perspective and long term perspective. The first is closely related to the recurrent idea of bouncing back an external shock and recovering former growth figures; the second relies on the multiple equilibrium criteria and in the ability of a region or a country to avoid being “locked into” a level of growth that is suboptimal; the third takes into account the multiple variables that compounds a society, such as the political and institutional areas; finally, the fourth, adds a long time analysis to the macroeconomic variables. According to the authors, resilience for both system and long term perspective would be “the study of the rise, stability and eventual decay of the institutions that underlie long-term regional economic growth” (HILL, WIAL AND WOLMAN, p.2, 2008).

On the other hand, the improvement of resilience capabilities would rely mainly on the action of three players. The measures undertaken by the government when facing an economic downturn will reflect on the speed of recovery of a country hit by a shock, therefore, accurate public policies is one way in which a country can show resilience. Industry and firms also play an important role when an economy is facing a crisis, and they can show resilience by investing in new technologies and markets, or by being able to keep it competitiveness. The institutional framework, likewise, can be the bastion of resilience in a region or country, and it works mainly through qualitative variables, such as which skills are commonly valuable in the labor-force of a society (HILL, WIAL AND WOLMAN, 2008).

Foster (2012) argues that there is still a clarification to be made, on whether resilience is classified as an outcome, meaning that an economy is resilient to the degree it recovers from a stress, or as a capacity, which refers to the conditions and attributes that a country or a region may have to recover from a shock. Put differently, this idea brings the question on whether resilience should refer to the post-stress recovery or to the pre-stress readiness. According to the author, most of the times the literature uses the term in a comprehensive manner, leaving room to the researches to apply it in the way it is most convenient. On the contrary, for public policies, split the two concepts would be of great value, as it generates a better picture of the economic situation.

The types of shocks that change the status quo are several, and may happen simultaneously. An economy can experience a downturn due to natural disasters, commodity price fluctuation, terrorist attacks, industry shift, sovereign debt or financial crisis beyond others. As resilience is not likely to be a static feature, meaning that the country may respond differently due to the origin of the disturbance, the aspects of each of the crisis must be discussed. Alongside, the same shock may affect economies in distinct ways, which instigates the study of resilience and how a country can achieve the necessary characteristics to overcome economic disturbances.

In this sense, would an economy barely hit by a stress be considered more resilient than another severely affected? Making use of this question, Simmie and Martin (2010) try to challenge the concept of resilience as an equilibrist definition, pointing that resilience should rather be seen as an evolutionary approach, in which the vulnerabilities and sensitivities of a system should be taken into account. The authors are skeptical with the idea that the more resilient the region, the less it would change over time, even in face of various shocks. For them, the concept of “creative destruction” is a best fit for the subject, and an economy would be classified as resilient if it is able to often rebuild itself in face of the new challenges, which brings resilience to a level of an ongoing process.

The concept of vulnerability is closely related to resilience and also important to be understood when analyzing the recovery capacity of an economy. According to Briguglio et al (2009), while resilience is policy induced, vulnerability is an inherent characteristic, meaning that the country cannot control for it. From this perspective, economic openness, export concentration and dependency on strategic imports are all features that make the country vulnerable and more biased to suffer from external events. Economic success, therefore, can arise because the country is inherently not vulnerable or due to its resilience.

Briguglio et al (2009) also made an effort to measure economic resilience by analyzing how efficient policies are in absorbing shocks in four broad areas, namely: macroeconomic stability, market efficiency, good political governance and social development. In the findings, they stated that the GDP of the countries can be explained by the levels of resilience and vulnerability. In the same way, Foster (2012) developed the Resilience Capacity Index (RCI) and applied the methodology to the US metropolitan areas. According to this approach, three are the main blocks, or capacities, that help to assess the resilience of a place: 1) regional economic, compound by income equality, economic diversification, regional affordability, and business environment;2) socio-demographic, made by educational attainment, percentage of population with disability, rate of poverty, and percentage of working age population; and 3) community connectivity, which refers to the percentage of the population born in the state, linguist connection, and age of housing in the region. As depicted, usually resilience is not the result of a single variable; rather it reflects the interplay of several characteristics.

In the same manner as the concept of resilience is surrounded by ambiguities, the way to assess it varies from study to study, which prevents the establishment of an empirical model. According to the OECD (2014), there are seventy indicators that could be used to detect the vulnerabilities of the countries and its resilience when facing a downturn. Some examples could be currency mismatches, degree of exposure from the banks, high risk premium on government debts, rate of innovation and ageing of the population. Although the several options and the fact that some independent variables are more frequent than others in the literature, the two main choices for dependent variable when measuring resilience are the change in the GDP growth or the variation in the unemployment rate.

According to Aron (1962), good economic institutions are those that provide security of property rights and relatively equal access to economic resources. The OECD (2014), by its turn, argues that openness and transparency of an institution are at the heart of resilient societies because they bring citizens and governments close together. For the Organization, since the impact of any shock depends on a jurisdiction’s institutional capacity to respond and rebound from it, institutions play a key role in strengthening resilience. Even though its importance, the impact of institutions in the recovery from a crisis has not been widely studied by the literature and questions such as how and when they cause growth still have to be answered.

As an attempt, Pike et al (2015) tried to measure the importance of governance and local institutions by conducting a comparative analysis of 39 local enterprise partnership emergent in England since 2010. As the study was at the local level, the interplay between the central government and the regions administration was measured by the level of centralizations of power and resources. This was due to the belief that the degree of independency would explain the role of institutions on the economic development of a region. In the findings, the path dependency excelled, in which the legacies from past and existing institutional environments and arrangements prefigure and shape the settings during periods of change and transition. Briguglioet at al. (2009) also measured the impact of institutions, but they used one variable called “good governance”, which derives from a component of the Economic Freedom of the World Index and accesses the legal structure and the security of property rights.

From another perspective, Foster (2012) points out that there are four types of institutional rigidities that may undermine resilience: 1) the inability to register a shock or to understand the nature of it, considering that stresses cannot be obvious in some cases; 2) the failure of feedback mechanisms on buffering against a shock and instead transmitting the impact of a stressor throughout the system; 3) the jurisdictional boundaries that may divide a country into a patchwork of political jurisdictions; and4) the restriction of experimentation and innovation, which are essential for resilience. This latest characteristic is related to the institutional “lock-in”, a process that occurs over time and turns an institution static and resistant to change.

The intellectual capital of a region or a country is also usually related to its resilience, and this factor has been widely explored by using variables such as the number of research institutions or the percentage of the adult populations with at least a high school education (Augustine et al., 2013). Generally, the more skilled the population, the better prepared they are likely to be when facing structural disruptions. In parallel, Di Caro (2015) believes that human capital can be seen through 3 aspects: education of workers, responsible for increasing the productivity and the generation of new ideas; education of entrepreneurs, given that skilled entrepreneurs develop new ways of production and organization; and externalities, which are the costs or benefits from people who are not involved in a certain process.

A different approach regarding intellectual capital comes from Diodato & Weterings (2014), who explores the resilience from the perspective of the worker. To explain their framework, they use the concepts of embeddedness, defined as the supply chain of the region and how it can propagate the initial shock within the economy; skill-related, which is the ability to find a job in another sector or migrate to a different region; and connectivity, known as the possibilities for interregional labor mobility. In this line, the authors affirm that what matters in the recovery capacity are the job opportunities available to workers after a sudden shock has forced them into unemployment. After applying this methodology on the Dutch regions, the authors showed that areas specialized in sector that are not highly intertwined in the supply network, but that related to one another through labor mobility are more resilient. In addition, the degree of connectivity to other counties is positively linked with the rebound of a shock.

The economic capital of a society can be measure by variables such as GDP, GDP per capita and inflation. Puzzled by how small states can generate a consistent GDP per capita despite their high external exposure, Briguglio et al (2009) found that resilience is positively correlated with GDP per capita and negative related to economic vulnerability, which are the intrinsic characteristics of a country or a region. However, as the OECD states, a robust GDP growth does not necessarily signals that an economy is healthy, as underlying risks, such as growing income inequality and deteriorating bank balance sheets are not captured by GDP measures.

The diversification of the economy also plays an important role on building its strengths. On analyzing the conditions in the region prior to the beginning of a downturn that are associated with resilience, Augustine et al. (2013) made use of the Herfindahl index of market concentration to test whether an economy that relies on few sectors can expose more vulnerabilities and if having more major export industries is better for the resilient capacity. As expected, economic diversity and a higher number of export industries is positively associated with resilience.

Other variable analyzed by the same research was the income equality, meaning how evenly income is distributed across a population. The expected outcome was that the more equal the region’s distribution of economic resources, the more cohesive the response to disturbance. To test it, the authors used the 80/20 ratio, which compares the per capita income at the 80% higher to the 20% poorest. Although the social capital is supposed to influence the outcomes of recovery, the variable chose by the study was not significant. Using the education and health indicator from UNPD Development Index (HDI), Briguglio et al. (2009) made an attempt to measure to which extent the relations within a society are proper developed. Although the correlation with good governance, the variable was still relevant to the study.

By focusing on the effect of the financial crisis on the 5 macro regions of Brazil, Diniz and Barbosa (2014) found that the most dynamic areas, which concentrate more people and more knowledge intensive activities, tend to be more resilient. Similarly, Di Caro (2015) divides an economy into three sectors, namely manufacturing, non-public services and public activities, and points out that the ability to bounce-back a distress seems positively related with the share of the manufacturing sector. According to him, this industry can stimulate higher investments, capital accumulation, productive linkages and a more competitive environment. On the contrary, the study also showed that there is a negative correlation with the presence of public activities, mainly because the public employment is less flexible. Paradoxically, Lagravinese (2015) conducted a study with the unemployment levels of Italian regions during several crises and stated that public employees and service industries answered better to the distresses, while the manufacturing sector felt more the recessions. One possible explanation for the disagreement is that while for Caro (2015) the focus of the analyzes was on the sectors that were severely hit by a shock but recovered quickly, from Lagravinese (2015) the analysis was on the industries that manage not to be strongly affected.

In the same way as the sectoral composition of an economy, Brakman et al (2015) stated that the degree and nature of urbanization is also important when considering resilience. Studying the effect of the last financial crisis and dividing the inhabitants into cities, metropolitan areas and rural population, the authors found that metropolitan areas were more resilient. According to them, this is the point where the two levels of analysis, urbanization and sectoral composition, meet each other, as the inhabitants of metropolitan areas are more likely to be employed by medium and high tech enterprises, which rebounded better the effect of the crisis.

Ballandet at (2015), by its turn, focused on the patent applications in 366 metropolitan areas in the US from 1975 to 2002. They tried to analyze resilience by the capacity of the cities on sustaining their production of technological knowledge during a technologic crisis, which is characterized as a period of negative growth in patenting activity. Instead of analyzing the engineering resilience, the authors centered on the evolutionary approach of it, in which the economies tailor themselves within time.

As exposed, there is a considerable set of variables that can impact the economic resilience of a place, and the selection of them is connected to the aim of the researches. The following part will be devoted to the analysis of a financial disturbance that led the countries to test its resiliency. This paper makes use of the financial crisis of 2007-2008 due to the proportions that it achieved, as the majority of the economies were hit by it, and because it is the most recent global downturn, which allows having a more up to date analysis on the capabilities of recovery from each country.

In the same way that countries can benefit from a more open world, by increasing trade and the flow of information and people, the global connectivity can also bring the disadvantages of contagious effect, which was seen during the last financial crisis. As known, what was initially only a subprime mortgage shock in the United States soon grew and reached the big portion of countries in the world. For Merrouche & Nier (2010), three factors contributed to the build-up of financial problems: 1) the rising global imbalances in capital flows, which lower the cost of wholesale funding and reduced long term interest rate; 2) the loose in the monetary policy, leading banks to take more risks; and 3) the inadequate supervision and regulation. In their findings, they show that the effect of capital inflows on the build-up is amplified where the supervisory and regulatory environment was relatively weak. In parallel, Verick & Islam (2010), agree on the points mention above, but add that the misperception of risks also played an important role on the spread of the crisis.

If closely looked, the roots of the imbalance can be found still in the first years of the decade, when the Federal Reserve, the national bank of the US, decided to lower the Federal funds rate as an attempt to avoid the consequences of the dotcom bubble and the terrorist attacks. This measure, together with the abundant credit from China, Japan and the Middle East, which pushed down global interest rates, helped to create a flood of liquidity. As a consequence, the excitement of the so called “Great Moderation”, meaning years of low inflation and stable growth, allowed low-quality borrowers to have access to cheap money and invest in the financial and in the housing sector, which pushed up the house prices and created an economic bubble.

As soon as the interest rates rose and the price of the houses dropped, the borrowers were not able to pay back its lending and the whole financial architecture behind the boost, based on mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO) began to be seen. With the defaults and the loss of confidence in the market, financial institutions started to declared bankruptcy. The proportion of the stress reached an unexpected level when the considered “too big to fail” corporations were not rescued by the US Government. The collapse of the Lehman Brothers, the fourth largest investment bank in the United States, in September 2008, is the main example of this case and had an important role on the spread of the crisis.

Despite having first hit developed economies, which usually have a bigger financial sector, and, therefore, are prone to feel the imbalances, the economic shock also reached emerging markets. The spread of the crisis happened mainly through the drop in international trade, but the fall in the worker’s remittances also contributed to the phenomena (DIDIER, HEVIA, SCHMUKLER, 2011). According to the authors, the main difference of this crisis compared to the previous is that in this time emerging markets were hit nearly as hard as rich countries, but they were able to avoid the amplification of external shocks that were typical of past episodes, which tended to end up in banking, currency and/or debt crisis. Due to the different outcomes, the financial crisis of 2007-2008also revived the study of resilience. By being better prepared and, therefore, more resilient, some developing economies were able to perform better in the post-crisis period as well.

Gregorio (2012) points out that the resilience showed during the crisis by a few emerging markets was due to 4 factors: good initial macroeconomic conditions, that grant strong monetary and fiscal stimulus; exchange rate flexibility, which allowed for sharp depreciation and eliminated incentives for speculation; strong, well-regulated and fairly simple financial systems; and high levels of international reserves. Didier, Hevia & Schmukler (2011) go in the same way and affirms that “the global crisis found many emerging countries with more fiscal space, better balance sheets, and the required credibility to conduct expansionary fiscal and monetary policies”. As depicted, the literature suggests that with a better economic framework and the awareness of risks from the governments, a share of the emerging countries were able to be more resilient during the last crisis.

Considering countries such as China and India, it is possible to see that they both managed to release stimulus packages based on the internal market, and the strong domestic demand allowed them to counter back the effects of the slowdown on international trade. With a growth of 8.7% and 6.7%, respectively, in the year of 2009, it can be suggested that both economies made good use of their tools on avoiding a recession (VERICK & ISLAM, 2010). Despite these results, some emerging market, mainly in Easter Europe and Central Asia performed very poorly on bouncing the economic effects. Although the distinct outcomes, it is a fact that the first worldwide recession since the Second World War led to a reduction of the world GDP by 0.6% from 2008 to 2009, and this figure could have been even worst in case countercyclical policies had not been used. With no doubt these numbers are important when analyzing a shock, nevertheless, it has to be stated that, even though rich economies attained lower rates of GDP growth or even faced a reduction during the crisis, such as the US contraction of 2.7% on the GDP on 2009, advanced economies grow slower on average than emerging economies independent of any crisis event.

Besides the drop in the GDP, the impact of the crisis was mainly felt by the raise on unemployment rates and the resurgence of poverty. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the number of unemployed persons in 2009 was estimated in 212 millions, which represented an increase of 34 millions on the figure from 2007. Narrowing the subject, Verick & Islam (2010) found out that a 1% drop on the GDP led to an increase of 0.47% on the unemployment rate. On the other hand, the resurgence of poverty was mainly felt on the developing and low income world, in which the recent and still vulnerable improvements on the income distribution were at a bigger risk. In line, the World Bank estimates that the recession resulted in an increase in poverty of 64 million people in the overall, and this number was encouraged by the food and energy price shock that hit a few developing countries (GLOBAL MONITORING REPORT, 2009).

As showed, some economies have been affected more than others, and to understand this pattern it is necessary to analyze the specifics of each country, and how prepared were they in case a stress arrived. The state of the economy, the fiscal space, the labor market and the institutional framework are all important factors to be studied. In parallel, as mentioned in the first section, the intensity in which the countries were hit by the downturn must be taken into consideration, meaning that some countries were more exposed due to, among others variables, the size of its financial market and its dependency on international trade. Although some years have passed since the shock, the topic is relevant and still offers some treats related to the post-phase, such as the risk of premature withdrawal of the stimulus package, the continuing and emerging imbalances and the challenge of setting an appropriate level of regulation for the financial sector.

Regarding the arguments exposed above, the financial crisis that started in the United States and quickly spread globally can be considered a good event to test the performance of the economies, mainly due to its proportion and intensity. Grounded on the literature review presented in the former sections, the next chapter will introduce the methodology and the data of this paper.

An econometric analysis aims at evaluating how the change in one variable can affect another one, and it can be held through three distinct structures, namely: cross sectional, time series and panel data. The first considers observations of different elements for a single period of time; the second follows one element over time; and the third combines multiple elements and time periods. As this paper aims at evaluating the effect of the last financial crisis on the resilience capacity of several countries within time and compares the different outcomes, the panel data model is expected to be the best choice.

According to Hsiao (2007), by increasing the number and the scope of observations, and by controlling the effect of unobservable variables, panel data offers a more accurate inference, which helps on analyzing the results of an event or policy. In the same way, a multidimensional dataset is more suited to observe the dynamics of change and allows for a deeper comprehension. The downside of the model lies mainly on the difficulties of gathering the necessary data, which sometimes has costs or is simply not available.

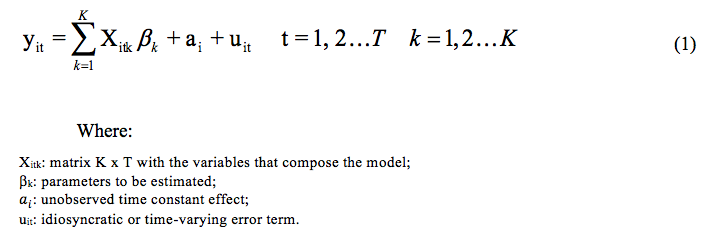

Wooldridge (2009) states that the pooled Ordinary Least Square (OLS) usually generates efficient estimators for panel data, but he also points that, “an alternative way to use panel data is to view the unobserved factors affecting the dependent variable as consisting of two types: those that are constant and those that vary over time” (p.459). In this way, k would denote the cross-sectional unit and t the time period, composing the formula as follows:

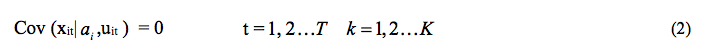

Known as fixed effect model, the model above removes time-invariant characteristics before the estimation of the parameters. Therefore, it can produce consistent estimators for ![]() evenif ai is correlated with xi. Nevertheless, if uit happens to be correlated with the explanatory variables or with the unobserved time-constant effect, the estimators obtained would be biased and inconsistent. As an alternative, the exposed equation could be estimated with random effect model, in which it is assumed that the covariance between Xit and ai, and between Xit and uit is equal to zero. In this way, the unobserved effect should be independent from all the explanatory variables within time:

evenif ai is correlated with xi. Nevertheless, if uit happens to be correlated with the explanatory variables or with the unobserved time-constant effect, the estimators obtained would be biased and inconsistent. As an alternative, the exposed equation could be estimated with random effect model, in which it is assumed that the covariance between Xit and ai, and between Xit and uit is equal to zero. In this way, the unobserved effect should be independent from all the explanatory variables within time:

To define which method of estimation is the most accurate to a given model, a series of tests should be conducted. The Chow test compares pooled OLS with fixed effect; Breusch-Pagan is used when choosing between pooled OLS and random effect; and the Hausman test is the solution to decide whether fixed or random effects would be a better choice. All of them were conducted on this research, and will be explained on the third chapter, together with the econometrical results.

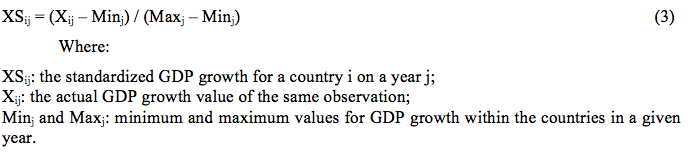

To reach the goals of this paper, it is needed to regress a model in which the resilience capacity of the countries is measured by a set of independent variables. According to the literature, GDP growth and unemployment rate are the most common indicators for resilience. Inspired by a model developed by Briguglio et al (2009) and using the data provided by the World Bank, this paper created two resilience index among the analyzed countries to use as dependent variable, one based on the GDP growth and the other on unemployment rate. After testing both of them, the index based on GDP growth was chosen, as it showed more relevant results. The index varies from 0 to 1, referring to the smallest and biggest growth figures, respectively. In this way, the dependent variable, named index_gdp (economy resilience measure by GDP growth), was created by the following formula (3):

In order to have a balanced dataset, states that missed more than four observations for a given variable were excluded from the research. Due to this selective procedure, the proposed index is composed of 78 countries. In parallel, as the paper search to evaluate the response of the economies to the latest financial crisis, the data starts in the year of 2007, when the crisis was first felt, still in the United States, and goes until 2014, the latest year with available figures for all the variables.

The independent variables selected to compose the model were also brought from the study of the literature on resilience and are expected to influence the ability of a country to deal with a shock. The name of the all the variables, as well as its descriptions and sources are provided in the table 1 below.

Table 1 –Independent Variables

Variable |

Description |

Source |

Institution |

Freedom from corruption. Variable extracted from the Index of Economic Freedom. |

Heritage Index |

Life |

Life expectancy at birth. Number of years a newborn infant would live if prevailing patterns of mortality at the time of its birth were to stay the same throughout its life. |

World Bank |

Tech (exp) |

Amount of high technology exports divided by the GDP at market prices. |

World Bank |

Educ |

Gross enrolment ratio on tertiary education for both sexes. |

World Bank |

Infras |

Access to improved sanitation facilities. |

World Bank |

Trade |

Sum of exports and imports of goods and services measured as a share of gross domestic product. |

World Bank |

Source: created by the authors.

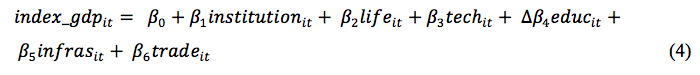

In this way, the regression employed in the current research would take the following form:

Taking the literature into account, it is expected to find a positive correlation between the resilience capacity of the countries with the strength of the institutions, the quality of life, the technology developed, the level of education and the investments on infrastructure. On the contrary, the degree of openness of a certain economy should be negatively correlated with the ability to bounce back a shock, as countries with a high level of trade were prone to face a deeper impact from the economic downturn. These expectations will be confirm or not in the next chapter, where the outcomes from the model will be discussed.

As explained on the previous chapter, the estimation of a panel data model can occur through different methods. In this paper, we considered pooled OLS, fixed effects and random effects. After testing the three distinct estimators, the results are presented in the table 2.

Table 2 – Determinants of the economic resilience, 2007-2014

Dependent variable: resilience index |

|||

Independent Variables |

Pooled OLS |

Fixed Effects |

Random Effects |

Institution |

0.248*** (0.001) |

0.003*** (0.001) |

0.006*** (0.001) |

Life |

0.069*** (0.007) |

0.052*** (0.009) |

0.068*** (0.008) |

Tech |

1.593** (0.645) |

-0.280 (0.433) |

-0.010 (0.434) |

Educ |

0.009*** (0.001) |

0.002** (0.001) |

0.003*** (0.001) |

Infras |

0.013*** (0.002) |

0.040*** (0.006) |

0.030*** (0.003) |

Trade |

-0.00*** (0.000) |

-0.001** (0.000) |

-0.001*** (0.000) |

Constant |

1.138*** (0.419) |

1.561** (0.653) |

1.125** (0.511) |

Source: created by the authors.*** p<1%, ** p<5%, *p<10%.

The first step to verify the robustness of the methods to the proposed model is to conduct a Breusch-Pagan, Chow, and Hausman test. The results of those tests show fixed effect as the best estimator.

Despite having selected the most accurate estimator, there is still the possibility of problems related to heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation. To avoid them and to guarantee the quality of the estimators, a robust fixed effect regression was conducted, bringing the results presented in the table 3.

Table 3 – Determinants of the economic resilience, 2007-2014, results for robust Fixed Effects

Dependent variable: resilience index |

||

Independent Variables |

Fixed Effects |

Robust Fixed Effects |

Institution |

0.003*** (0.0011) |

0.003* (0.0019) |

Life |

0.052*** (0.0095) |

0.052*** (0.0161) |

Tech |

-0.280 (0.4332) |

-0.280 (0.6109) |

Educ |

0.002** (0.0012) |

0.002 (0.0018) |

Infras |

0.040*** (0.0061) |

0.040*** (0.0135) |

Trade |

-0.0013** (0.0006) |

-0.0013 (0.00091) |

Constant |

1.561** (0.653) |

1.561 (1.127) |

Source: created by the authors

Using a 10% level of significance, we can observe that institutions do play an important role on the ability of the countries of bouncing back a shock. As the proxy used for institutions was the freedom from corruption, it is possible to state that institutional frameworks that enjoy a better level of accountability are prone to have advantages when facing economical issues. This factor can also be related to the readiness of the government on taking actions when an unexpected event occurs or by taking precautions when there is time. This finding also corroborates the idea of the OCDE (2014). According to the organization, openness and transparency are central on constructing a resilient society, because they connect government and citizens. As quantifying the power of institutions on resilience has been a challenge for the literature, the proxy used in the model could be of great value for further researches.

Life expectancy, referred at the model as life, also showed to be a significant variable on explaining how likely the countries are to rebound a downturn. According to the parameter, the longer the average of years lived by a population, the more resilient its country was during the last financial crisis. As life expectancy is closely related to quality of life, it was already expected that economies with more health and productive workers would generate a better outcome when dealing with a shock. This finding meets the result provided by the work of Briguglio et al (2009), in which the variable health, also measured by the expectancy of life at birth, showed to be positively correlated with economical resilience.

Other factor relevant on explaining how resilient the countries were to the latest global shock is infrastructure. According to the result, states that offer better facilities to its populations are also better prepared to bounce back a crisis. Infrastructure can refer to the quality of roads, electrical grids or telecommunication, which are factors that make the country attractive to foreign investments and improve the business environment. On the other hand, infrastructure can also be interpreted as the provision of basic life conditions. As the proxy used for infrastructure on this paper was the percentage of improved sanitary facilities, it is possible to picture that providing a hygienic environment, with the treatment of water and the absence of diseases allows a country to be more productive and make use of its skills to the fullest.

Despite being mentioned in the literature as the most important factor on the spread of the crisis, which is also related to the intensity of the downturn faced by each country, the variable trade was not statistically significant for this research. In this way, the openness of the economy cannot explain the resilience of the countries to the shock studied in this paper. Similarly, the level of education, even though being pointed by the literature as an important factor on helping a country to face a structural disruption, was not statically significant in the model. Lastly, the variable technology had the same outcome, and was not a relevant factor for the research. This latest result goes against previous works, such as the one from Diniz & Barbosa (2014), who found a positive and significant correlation between knowledge intensive activities and resilience.

The results discussed above showed that explaining economical resilience is still a difficult subject. As there are several variables that could be used in a model, it is according to the will of each author to choose the ones believed to be the most accurate. Similarly, the crisis studied may vary, as well as its intensity. Due to these facts, it is also possible to understand that the significance level and the influence of the variables on resilience may vary within researches. In the present paper, the expected correlation between the dependent variable and the independent factors was accurate, nevertheless three of the selected variables to explain the behavior of economic resilience showed not to be significant, which is more than the prediction.

The efforts to quantify economic resilience have been done within the years, and the latest global crisis has only increased the interest of academics on the topic. As mentioned, there is no single way to interpret resilience, mainly because the broadness of the concept and the fact that the variables influencing it may vary from shock to shock. Thereby, this paper was an attempt to quantify economic resilience during the latest financial crisis and to provide useful information for the players at the state level.

Although GDP growth is a useful parameter to show the economic situation of a country and how hard was the impact of a given crisis, it is worth restating that the most developed countries are expected to have a small variation on their growth path. As this research proposed on observing economic resilience as the ability of maintaining the current growth figures, and not on recovering the previous data, this fact should not be of major concern. In the same way, as pointed on the first chapter, a robust GDP growth can still mask some risks, such as income inequality. Therefore, despite the fact that GDP growth is a way to measure the economical resilience of a country, the arguments mentioned above help on understanding why the analysis and the measurement of resilience is still a topic surrounded by ambiguities.

Concerning the goals of the research, after testing the six variables selected to compose the model, it was observed that only three of them were significant on explaining resilience during the last shock. This finding was surprising, as the insignificant variables education, trade and technology were recurrent on the literature review. One possible explanation for that could be that their effects were already absorbed by the other variables. Although life and infrastructure showed to be more important on explaining economical resilience in the proposed robust model, the role of institutions was also statistically significant, proving that the readiness of the governments on taking action or even on preventing from collapses can help on explaining the performance of the countries during the latest global crisis.

As pictured, not all the variables that may have influenced the resilience capacity during the studied economic slump could fit in this model. Due to the limitation of some data and the impracticability of adding too many factors, which is likely to increase the problems with multicollinearity, there is space for future researches to focus on variables that were not explored in the current paper.

ARON, R. (1962). Paix et Guerre entre les Nations. Revue Française de Science Politique, 4 : 963-979.

AUGUSTINE, N; WOLMAN, H.; WIAL, H.; MCMILLEN, M. (2013). Regional Economic Capacity, Economic Shock and Economic Resilience. Building Resilient Regions closing symposium at the Urban Institute, Washington, DC.

BLANCHARD, O; FARUQEE, H; DAS, M. (2010), The Initial Impact of the Crisis on Emerging Market Countries, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity,Spring:263-307.

BRAKMAN, S. GARRETSEN, H.; MARREWIJK, C. (2015). Regional resilience across Europe: on urbanisation and the initial impact of the Great Recession. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8: 225-240.

BRIGUGLIO, L., CORDINA, G; BUGERA, S.; FARRUGIA, N. (2009). Economic Vulnerability and Resilience: concepts and measurements. Oxford Development Studies, 37:3, 229-247.

CALDERA SÁNCHEZ, A.; RASMUSSEN, M; RÖHN, O. (2015). Economic resilience: what role for policies? OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1251, OECD Publishing, Paris.

DICARO, P.(2015). Recessions, recoveries and regional resilience: evidences on Italy. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8: 273-291.

DIDIER, T; HEVIA, C.; SCHMUKLER, S. (2011), How Resilient Were Emerging Economies to the Global Economic Crisis? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, nº 5637.

DINIZ, G.F.C.; BARBOSA, L. O. S. (2014). Resiliência regional: uma aplicação às Regiões brasileiras entre 2008-2010. XVI Seminário sore a Economia Mineira, Diamantina, Brasil.

DULLIEN, S; KOTTE, D; MÁRQUEZ, A; PRIEWE, J. (2010). The fiancial and economic crisis of 2008-2009 and developing countries. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. United Nations Publications, New York and Geneva.

FINGLETON, B., GARRETSEN, H. and MARTIN, R. (2012), Recessionary Shocks and Regional Employment: evidence on the resilience of U.K. regions. Journal of Regional Science, 52: 109–133

FOSTER, K. (2012). In Search of Regional Resilience. Urban and Regional Policy and Its Effects: Building Resilient Regions. Ed. Margaret Weir et al. Brookings Institution Press, 24–59.

GREGORIO, J. (2013). Resilience in Latin America: lessons from macroeconomic management and financial policies. International Monetary Fund Working Paper, 13/259, Washington, DC.

HILL, E; St. CLAIR, T; WIAL, H; WOLMAN, H; ATKINS, P.; BLUMENTHAL, P; FICENEC, S; FRIEDHOFF, A. (2010). Economic Shocks and Regional Economic Resilience. Conference on Urban and regional Policy and its effects: building resilient regions, Washington, DC.

HILL, E.; WIAL, H.; WOLMAN, H. (2008). Exploring regional economic resilience. Institute of Urban and Regional Development, No. 04.

HSIAO, Cheng. (2007). Panel Data Analysis: advantages and challenges. Sociedad de Estatística e Investigación Operativa. 16: 1-22.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. (2009). World Economic Outlook Database. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2009/02/weodata/index.aspx.

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION. (2010). Global Employment Trends.

LAGRAVINESE, R. (2015). Economic crisis and rising gaps North-South: evidence from the Italian regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8: 331-342.

MERROUCHE, O; NIER, E. (2010). What caused the global financial crisis? Evidences on the drivers of financial imbalances 199-2007. International Monetary Fund Working Paper, 10/265, Washington, DC.

MARTIN, R.; SUNLEY, P.; TYLER, Peter. (2015). Local growth evolutions: recession, resilience and recovery. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8, 141-148.

OECD. (2014). Overview Paper on Resilient Economies and Societies. OECD Publishing, Paris.

PIKE, A.; MARLOW, D.; MCCARTHY, A.; O’BRIEN, P.; TOMANEY, J. (2015). Local institutions and local economic development: the Local Enterprise Partnerships in England, 2010. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8: 185-204.

SIMMIE, J.; MARTIN, R. (2010). The economic resilience of regions: towards na evolutionary approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3, 27-43.

The origins of the financial crisis: crash course. (2013, Septemer, 7). http://www.economist.com/news/schoolsbrief/21584534-effects-financial-crisis-are-still-being-felt-five-years-article.

THE WORLD BANK. (2009). Global Monitoring Report: a development emergency.

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGLOMONREP2009/Resources/5924349-1239742507025/GMR09_book.pdf.

WOOLDRIDGE, J. (2009). Introductory Econometrics: a modern approach. Mason, OH: Thomson/South-Western.

1. Master in Economics – Utrecht University, The Netherlands. Email: repostal@gmail.com

2. Assistant professor of Economics at Federal University of Ouro Preto/Brazil. Email: hedercarlos@yahoo.com.br