Vol. 38 (Nº 24) Año 2017. Pág. 18

Andrii TROFIMOV 1; Iuliia BONDAR 2; Daria TROFIMOVA 3; Kateryna MILIUTINA 4; Iaroslav RIABCHYCH 5

Recibido: 10/04/16 • Aprobado: 20/04/2016

ABSTRACT: This article gives a detailed analysis of such phenomena as work engagement and describes it as a significant factor of influence on the level of organizational commitment. The methods proposed to analyze the results of this research are descriptive, regressive and correlation analysis. The article declares connection between such psychological phenomena as organizational loyalty, psychological capital, work engagement and subjective hope. The conclusions are the following: the most powerful connection between all this factors is between organizational commitment and work engagement. It means, that the more employee of organization feels himself engaged in work, the more level of organizational commitment he has. |

RESUMO: Este artículo da un análisis detallado de fenómenos tales como la participación en el trabajo y lo describe como un factor significativo de influencia en el nivel de compromiso organizacional. Los métodos propuestos para analizar los resultados de esta investigación son análisis descriptivo, regresivo y de correlación. El artículo declara conexión entre fenómenos psicológicos tales como lealtad organizacional, capital psicológico, compromiso laboral y esperanza subjetiva. Las conclusiones son las siguientes: la conexión más poderosa entre todos estos factores es entre el compromiso organizacional y el compromiso laboral. Significa, que cuanto más empleado de la organización se siente comprometido en el trabajo, más nivel de compromiso organizativo tiene. |

Organizational commitment takes an important role in retention and stuff turnover in the organizations. Such factors as work engagement, psychological capital and subjective hope are not described fully in previous researches and we hope that this investigation can shed light on relationships between them. The understanding of it and connections between organizational commitment and factors which influence it can help us to make organizations stable and decrease stuff turnover.

Engagement takes place when people are committed to their work and the organization and are motivated to achieve high levels of performance. According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2012): “Engagement has become for practitioners an umbrella concept for capturing the various means by which employers can elicit additional or discretionary effort from employees – a willingness on the part of staff to work beyond contract”.

Kahn (1990) defined employee engagement as ‘the harnessing of organization members’ selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances’. There have been dozens of definitions since the explosion of interest in the concept during the 2000s. Chalofsky and Krishna (2009) stated that engagement was ‘the individual’s involvement and satisfaction with as well as enthusiasm for work. A later definition was produced by Dick and Metcalfe (2001) who defined engagement as ‘an individual’s purpose and focused energy, evident to others in the display of personal initiative, adaptability, effort and persistence directed towards organizational goals’. Barkhuizen and Rothmann (2006) tell that engagement as having three core facets:

1) Intellectual engagement – thinking hard about the job and how to do it better;

2) Affective engagement – feeling positively about doing a good job;

3) Social engagement – actively taking opportunities to discuss work-related improvements with others at work.

The term “engagement” can be used in a specific job-related way to describe what takes place when people are interested in and positive – even excited – about their jobs, exercise discretionary behavior and are motivated to achieve high levels of performance. It is described as job or work engagement. Sparrow (2013) stated that: “Put simply, engagement means feeling positive about your job”. Organizational engagement focuses on identification with the organization as a whole. Coffman and Gonzalez-Molina (2002) emphasized the organizational aspect of engagement when they referred to it as “a positive attitude held by the employee towards the organization and its values”. This definition of organizational engagement resembles the traditional notion of commitment. Perhaps the most illuminating and helpful approach to the definition of engagement is to recognize that it involves both job and organizational engagement as suggested Sparrow (2013).

Organizational commitment has been defined as the magnitude of an employee’s relationship with a company. Many times, it is related to various factors such as the employee’s belief in the organization’s goals and values, the employee’s attitude in giving effort for the company and the desire to remain with the company. Organizational commitment is described by Meyer and Allen (1990) as: “the emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in, the organization”. Elizur, Kantor, Yaniv and Sagie (1996) note that there are two types of commitment. The first one is moral commitment, which can be described as the attachment or loyalty to something (in this case the hospital), and the second one is calculative commitment, which can be described as the potential benefit a person would gain by being committed.

Mowday, Steers and Porter (1981) explain that there are three types of organizational commitment. Affective commitment can be seen as the first domain, which includes the strength of a person’s identification with and participation in the organization. They also have the opinion that individuals possessing affective commitment stay within the organization, not because they have to or feel obligated to do so, but because they want to stay. Continuance commitment is based on the degree to which the person perceives the costs of leaving the organization as greater than staying, or simply that the person remains committed because it is their only option (Allen, Meyer, 1990).

Meyer and Allen (1990) identify two mechanisms that can contribute to normative commitment. The first one is a strong correlation between the values of the individual and the values of the organization. The second mechanism is of a more instrumental nature associated with reward systems. Thus, an employee may be rewarded according to certain criteria, and may then in return feel obligated to stay with the company (Goffman, 1961). Therefore, individuals who experience normative commitment, are committed to the organization because they feel it is the right thing to do.

Work engagement. According to Bakker A., Schaufeli W., Leiter M., Taris T. (2008) and Schaufeli W., Bakker A., Salanova M. (2006), engagement can be defined as: “the positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication and absorption”. Engagement can also be seen as a state of mind, and is not focused on a specific object, event, individual or behavior (Schaufeli, 2013).

Some researchers agree that work engagement not only assists in the decrease of perceived levels of occupational stress (Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova, 2006), but also brings about organizational and financial success through an increase in employee motivation and organizational commitment. Disengaged employees tend to distance themselves from their work roles and to withdraw cognitively from the current work situation. Therefore, work engagement is an important factor within any organization, and more specifically within social service occupations such as nursing, especially since these employees interact with various social systems within the organization and show the lowest level of work engagement.

Barkhuizen and Rothmann (2006) state that employees see engagement as a means of repayment toward the organization. Freeney and Tiernan (2006) also explain that engagement can be seen as a constructive indicator of commitment. Thus, nurses can choose on what level or to what degree they want to be engaged in their work, which, in turn, influences their loyalty and commitment to the organization (Kahneman, 2000).

Therefore, a higher level of work engagement benefits the employer in that it has an impact on the competitive advantage of the organization (Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova, 2006).

According to the Freeney and Tiernan (2006), work engagement is seen as involving both emotional and rational factors relating to work and the overall work experience. Emotional factors are those leading to a sense of personal satisfaction, and the inspiration and affirmation received from the work and being part of the organization. This could come from having a strong sense of personal accomplishment in the job they perform. It can therefore be concluded that engagement is related to meaningful work. And, therefore, such phenomena as work engagement can influence the forming of organizational commitment.

Psychological Capital (PsyCap). PsyCap is defined as being “an individual’s positive psychological state of development characterized by: (1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering towards goals, and when necessary, redirecting paths to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and (4) when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resiliency) to attain success”. PsyCap can be viewed as an important personal resource. Personal resources help to attain goals, because individuals with many resources can better cope with the hindrance demands they face. Thus PsyCap will help employees meeting the challenges of their work. PsyCap represents the positive resources individuals possess, which enable them to move towards flourishing and success (Luthans et al., 2007). According to Bandura (2000), the most important determinants of the behaviors people choose to engage in and how much they persevere in their efforts in the face of obstacles and challenges are “people’s beliefs in their capabilities to produce desired effects by their own actions”. Thus, individuals with high self-efficacy are more willing to spend additional energy and effort on completing a task or an assignment and hence to be more involved when studying with high level of absorption. Optimism is the belief that good things will happen. Thus optimistic individuals having these self-beliefs expect success when they are presented with challenge.

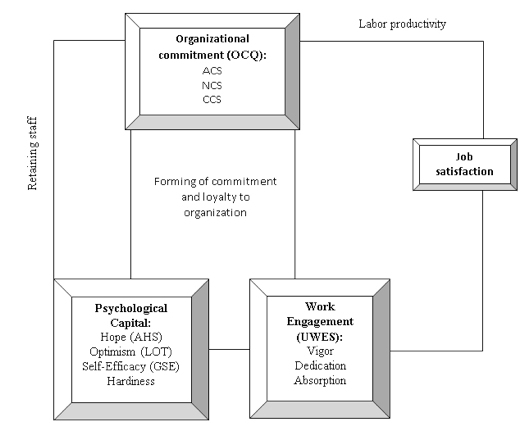

The literature review of psychological phenomena’s, which we investigate in our paper, such as – work engagement, organizational commitment, psychological capital and hope, gives us a possibility to build an operational theoretical model, which you can see below:

Figure 1. The operational model, created by the authors

According to the concepts, described below and operational model that were built we can deduce the purpose of our study.

The goal of our investigation was the identification of factors which influence organizational commitment and find key causes which will make the employee more committed to the organization.

We assumed that such psychological phenomena as work engagement, hope and psychological capital will be such factors and play an important role in increasing employee’s organizational commitment

We truly believe that there are some statistically significant connections and influence between organizational commitment, work engagement and psychological capital and it can help in retention processes (to understand the factors which increases the level of organizational commitment and reduce staff turnover) in variety of organizations.

Descriptive, regressive and correlation analysis using SPSS package (using Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal — Wallis test) (Cohen, 1988).

102 of men and 76 of women took part at research, 178 people in total. All the participants have work and are employed in company from less than a year till 5 years and more from three different spheres of work (IT industry, trade and car service).

Table 1. The profile of researches

Respondent’s profile |

Categories |

Frequency |

Percent |

Gender |

Male |

102 |

57.3 |

Female |

76 |

42.7 |

|

Age |

Before 25 |

42 |

23.9 |

26-30 |

48 |

27.3 |

|

31-40 |

55 |

31.3 |

|

41-50 |

19 |

10.8 |

|

51 and more |

12 |

6.8 |

|

Educational profile |

College |

18 |

10.1 |

High Education |

151 |

84.8 |

|

Post Graduate |

9 |

5.1 |

|

Specialization |

Software Engineers |

58 |

33.3 |

other |

116 |

66.7 |

|

Organisational Tenure |

Less than a year |

57 |

32.0 |

from 1 to 3 years |

57 |

32.0 |

|

from 3 to 5 years |

20 |

11.2 |

|

More than 5 years |

44 |

24.7 |

|

Position of company |

leader |

49 |

27.5 |

Not a leader |

129 |

72.5 |

|

Job satisfaction |

Not satisfied |

3 |

1.7 |

rather dissatisfied than satisfied |

8 |

4.5 |

|

difficult to define |

22 |

12.4 |

|

rather satisfied than dissatisfied |

88 |

49.4 |

|

fully satisfied |

57 |

32.0 |

According to Meyer and Allen (1990), this measure views organizational commitment from three perspectives: affective, continuance and normative commitment. Affective commitment refers to employees’ degree of emotional attachment to and identification with the organization. The continuance component refers to the level of commitment that employees associate with the organization based on the perceived costs of leaving the organization. Thirdly, the normative component refers to the employee’s feeling that they have a responsibility to remain within the organization and not leave it for another one. The 18 items are measured on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), which includes items such as: “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career in this organization”, “I do not feel any obligation to remain with my current employer” and “Right now, staying with my organization is a matter of necessity as much as desire”. High scores on the affective commitment scale (ACS), normative commitment scale (NCS) and continuance commitment scale (CCS) are an indication of organizational commitment. Research conducted by Meyer and Allen indicates that the reliability figures for the three scales of commitment by means of coefficient alpha values are above the acceptable levels and are as follows: ACS 0.87, CCS 0.75 and NCS 0.79.

Russian validated version of the questionnaire was done by Dotsenko (2001) and then improved by Dominiak (2006).

The scale developed by Schaufeli et al. (2006; 2008) was utilized as a measure of work engagement amongst nurses at hospitals. This 17item questionnaire is measured on a seven-point frequency scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always); the measure has three sub-scales: vigour, dedication and absorption. Example items are, “I feel strong and vigorous in my job”, “I always persevere at work, even when things do not go well” and “In my job, I can continue working for very long periods at a time”. Regarding internal consistency, Cranach’s alpha coefficients have been determined at between 0.68 and 0.91 (Schaufeli et al., 2006; 2008). “Utrecht Work Engagement Scale” (UWES) (Schaufeli et al., 2006; 2008) was used in our investigation in adaptation by Kutuzova (2006).

Psychological Capital (PsyCap) is a positive state-like capacity that has undergone extensive theory-building and research. The PCQ, a measure of PsyCap with 24 items, has undergone extensive psychometric analyses and support from samples representing service, manufacturing, education, high-tech, military and cross cultural sectors. Each of the four components in PsyCap is measured by six items. The resulting score represents an individual's level of positive PsyCap (Luthans et al., 2007). Validated version of the questionnaire was made on the basis of paper of Moskaleno (2014). Primary approbation and adaptation were made.

The results of the study shows that one-stage reliability, internal consistency points of sub scales of PsyCap, reflecting adequacy assignment statements material with the respective scale questionnaire are not significantly deviates from the author: coefficient α-Cronbach for sub-scales are within 0,69-0,72 (Moskaleno, 2014).

For constructive validity analysis, we used the procedure "convergent validation" - checked correlations between PsyCap scales and related scales from the questionaries’ which were already validated in Russian.

Description of Measure: A 12-item measure of a respondent’s level of hope. In particular the scale is divided into two subscales that comprise Snyder’s cognitive model of hope: (1) Agency (i.e., goal-directed energy) and (2) Pathways (i.e., planning to accomplish goals). Of the 12 items, 4 make up the Agency subscale and 4 make up the Pathways subscale. The remaining 4 items are fillers. Each item is answered using an 8-point Likert-type scale ranging from Definitely False to Definitely True. It should be noted that the authors recommend that when administering the scale, it is called “The Future Scale”. Russian validated version of Adult Hope Scale was made by Mudzybaev (1999).

Influence of attitude to work (alienation or dedication), psychological capital, dispositional optimism and hope for the organizational loyalty

Using multiple regression analysis, it was revealed that only such factors as work attitude (dedication and alienation from work), and hope significantly affect organizational loyalty.

The greatest contribution to the Organizational Loyalty brings a passion for work as a factor Energy (Beta = 0,516), the lowest – Alienation from work (Beta = -0,182).

Since Organizational Loyalty depends on the sex, it makes sense to investigate the predictors of Org. factor (work engagement).

Men Organizational Loyalty predict (the coefficient of determination R Square = 0,368) such factors as Hope, Energy (work engagement), Alienation and Enthusiasm (work engagement).

Since Organizational Loyalty depends on the administrative status, it makes sense to investigate the Loyalty for men and women separately.

Women Organizational Loyalty predicts (coefficient of determination R Square = 0,233) only Energy predictors of Organizational Loyalty to leaders and managers separately.

Organizational Loyalty is predicted for the leaders by (coefficient of determination R Square = 0,212) only Enthusiasm Factor (work engagement)

Organizational Loyalty is predicted for non-leaders by (the coefficient of determination R Square = 0,315) such factors as Energy (work engagement), Hope and Optimism (the factor of psychological capital).

Table 2. Results of research

|

R Square |

Standardized Coefficients Beta |

|||||

Energy |

Enthusiasm |

Alienation from Work (Scale Alienation test) |

Hope (Hope Scale) |

Optimism (PsyCap) |

Self-efficacy (PsyCap) |

||

Commitment (total)

|

,307 |

,516 |

- |

-,182 |

-,300 |

- |

- |

Commitment (total) Men

|

,368 |

,393 |

,195 |

-,222 |

-,417 |

- |

- |

Commitment (total) Women

|

,233 |

,483 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Commitment (total) leaders |

,212 |

- |

,460 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Commitment (total) non leaders |

,315 |

,531 |

- |

- |

-,294 |

,179 |

- |

Affective commitment |

,376 |

|

,097 |

,031 |

|

|

- |

Affective commitment Men |

,396 |

|

,479 |

-,243 |

|

|

-,163 |

Affective commitment Women |

,357 |

|

,598 |

|

|

|

- |

Affective commitment leaders |

,527 |

|

,726 |

|

|

|

- |

Affective commitment non lead |

,322 |

|

,458 |

-,180 |

|

|

- |

Continuance commitment |

,189 |

,415 |

|

|

-,406 |

|

- |

Continuance commitment Men |

,299 |

,550 |

|

|

-,542 |

|

- |

Continuance commitment Women |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Continuance commitment lead |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Continuance commitment non lead |

,262 |

,418 |

|

|

-,608 |

|

,266 |

Normative commitment |

|

,451 |

|

-,184 |

-,245 |

|

- |

Normative commitment Men |

,285 |

,430 |

|

-,271 |

-,323 |

|

-,202 |

Normative commitment Women |

,247 |

,497 |

|

|

|

|

- |

Normative commitment lead |

,413 |

,456 |

|

-,381 |

|

|

- |

Normative commitment non lead |

,263 |

|

|

|

-,215 |

,173 |

- |

In the hypothesis we declared that there is some connection between such psychological phenomena as organizational loyalty, psychological capital, work engagement and subjective hope. After research we’ve made we can postulate the following conclusions: the most powerful connection between all this factors is between organizational commitment and work engagement. It means, that the more employee of organization feels himself engaged in work, the more level of organizational commitment he has. Also this connection depends from such factors as sex and administrative status. All our results should be investigated more deeply and used for retention and decreasing turnover in organizations of different fields and structures.

Allen, N.J., Meyer, J.P. (1990). The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organisation. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18.

Bakker, A., Schaufeli, W.B., Leiter, M.P., Taris,T.W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22, 187–200.

Bandura, A. (2000). Theory of social acquisition. Moscow: Publishing House „Eurasia”.

Barkhuizen, N., Rothmann, S. (2006). Work Engagement of academic staff in South African higher education institutions. Management Dynamics, 15, 38-46.

Chalofsky, N., Krishna, V. (2009). Meaningfulness, Commitment, and Engagement: The Intersection of a deeper Level Intrinsic Motivation. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 11, 189–203.

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. Employee Engagement Factsheet (2012). Lancaster, Lancaster University Management School. Retrieved from: www.cipd.co.uk/hr-resources/factsheets/ employee-engagement.aspx

Coffman, C., Gonzalez-Molina, G. (2002). Follow This Path. New York: Warner Business Books Conference Board.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for Behavioural Sciences. London: Routledge.

Dick, G., Metcalfe, B. (2001). Managerial factors and organizational commitment. The International Journal of Public Sector Management, 14, 111–128.

Dotsenko, E. V. (2001). Measuring the commitment of the company staff via questionnaire technique. Materials All-Russia scientific-practical conference „Business Psychology: Human Resource Management in public organizations and commercial structures”. Saint Petersburg: GP «IMANTON».

Elizur, D., Kantor, J., Yaniv, E., Sagie, A. (1996). Importance of life domains in different cultural groups. American Journal of Psychology, 121(1), 35-46.

Freeney, Y., Tiernan, J. (2006). Employee engagement: An overview of the literature on the proposed antithesis to burnout. Irish Journal of Psychology, 27, 130-141.

Goffman, E. (1961). Encounters: Two studies in the sociology of interaction. American Antropologist, 65(6), 1416-1417.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724

Kahneman, D. (2000). Experienced Utility and Objective Happiness: A Moment Based Approach. In: Kahneman, D., Tversky, V. (2000). Choices, Values and Frames. New York: Cambridge University Press and the Russell Sage Foundation.

Kutuzova, D. A. (2006). Organization of activity and style of self-control as factors of professional burnout educational psychologist. PhD Dissertation. Moscow.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B., Avey, J. B., Norman, S. M. (2007). Psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60, 541-572.

1. Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Department of Psychology, PhD, Associate Professor, E-mail: hrta@bigmir.net

2. Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Department of Organizational Psychology, Master

3. Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Department of Psychology, PhD in Psychology

4. Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Department of Psychology of Development, Doctor of Psychological Sciences, Professor

5. Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Department of Psychology of Development, PhD in Psychology