Vol. 39 (Nº36) Year 2018. Page 26

Vol. 39 (Nº36) Year 2018. Page 26

Dmitry KLIMOV 1; Lyubov BELYAEVA 2

Received: 18/05/2018 • Approved: 30/06/2018

ABSTRACT: The article makes an attempt to use historico-geographical approach to analyze migration processes, which makes it possible to compare the migration tendencies of the past and present, to approach forecasting and control issues. As a representative territory, the Lipetsk region was chosen as an old-cultivated region within which various historical and geographical factors influencing the qualitative and quantitative parameters of migration processes and their dynamics have been analyzed. During the research, the authors proceeded from the fact that in different historical periods associated with the development of a particular territory, there were different migration trends determined by both internal and external factors. Ultimately, these trends could have an impact on the subsequent migratory behavior within the given territory. During the research, certain historical periods characterized by stable migration trends were distinguished. The factors determining these trends have been dominated by general trends typical for all regions of the world, namely “rural-to-urban” migration flows and specific factors characteristic of the country as a whole (a negative migration balance associated with the Revolution and the Civil War, a migration gain in the 90s of the 20th century, etc.), and local factors determined by the specifics of the economic complex formation in the region. |

RESUMEN: El artículo hace un intento de utilizar el enfoque histórico-geográfico para analizar los procesos de migración, lo que permite comparar las tendencias de migración del pasado y el presente, para abordar problemas de previsión y control. Como territorio representativo, la región de Lipetsk fue elegida como una región de antiguo cultivo en la que se han analizado diversos factores históricos y geográficos que influyen en los parámetros cualitativos y cuantitativos de los procesos de migración y su dinámica. Durante la investigación, los autores partieron del hecho de que en diferentes períodos históricos relacionados con el desarrollo de un territorio en particular, había diferentes tendencias de migración determinadas por factores internos y externos. En última instancia, estas tendencias podrían tener un impacto en el comportamiento migratorio posterior dentro del territorio dado. Durante la investigación, ciertos períodos históricos se caracterizaron por las tendencias de migración estable que se distinguieron. Los factores que determinan estas tendencias han estado dominados por las tendencias generales de todas las regiones del mundo, a saber, los flujos migratorios "rurales a urbanos" y los factores específicos del país en su conjunto (un saldo migratorio negativo asociado a la Revolución y el Guerra, una ganancia de migración en los años 90 del siglo 20, etc.), y factores locales determinados por los detalles de la formación del complejo económico en la región. |

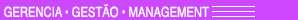

Human migration is as old as humankind (Rybakovsky, 2003, p. 4). With the seeming simplicity of understanding migration process in contemporary scientific literature, the term “human migration” does not have a clear and unambiguous definition yet. This can be accounted both for the fact that human migration is an extremely multifaceted phenomenon and that migration is studied at the intersection of various scientific disciplines. Therefore, there are a large number of definitions of the “human migration” concept. A human migration specialist, V.A. Iontsev counted about 36 definitions of this term in Russian-language publications alone (Vasilenko, 2013b, p. 105). According to the authors, the most successful interpretation of the “human migration” concept has been given by L.L. Rybakovsky: it is a territorial movement that occurs between different populated areas of one or several administrative-territorial units, regardless of duration, regularity and goal (Rybakovsky, 2003, p. 6). Migration in turn requires classification (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Types of human migration

Source: (Plisetskiy, 2003).

Human migration has reflected in various aspects of socioeconomic and cultural life of many regions, both in the past and in the present.

Despite various authors’ attempts to formulate universal theories of human migration (E. Ravenstein (1876), Everett S. Lee (1966), W. Zelinsky (1971), V.A. Iontsev (1999)), one has to agree with the idea of P.V. Vasilenko that “every migration story is individual” (Vasilenko, 2013a, p. 37). To solve a set of problems related to migration processes both at the global and regional levels, it is not only necessary to describe the current trends associated with population movement (statistical record), but also to explain them (identifying key factors), to predict future migration processes, and to develop mechanisms to control these processes. In this regard, studying the historical and geographical peculiarities of migration processes in individual territories appears very relevant. This allows one to compare the past and present migration trends, to approaching forecasting and control issues.

This paper deals with the historico-geographical analysis of migration processes in the Lipetsk region, while identifying key migration trends and factors that affect them. Analyzing the above classification, it can be noted that not all migration types can be detected using traditional statistical methods of research. Since this paper considers migration processes in the Lipetsk region, the study will be limited only to those types of migration for which there is a sufficient amount of statistical data. Consideration of the current migration picture in the Lipetsk region and the analysis of the existing problems related to migration should be preceded by a study of migration processes in the present-day Lipetsk region territory in the past.

The works of canonical migration process theorists (Zelinsky (1971), Lee (1966), Rybakovsky (2003)) have served as a theoretical foundation for the study. It cannot be said that a large number of papers have been devoted to comprehensive research (including historico-geographical analysis) of migration processes in the Lipetsk region. This refers to the analysis of both past and present migration processes. In this regard, the main literature sources of research in many respects were historical works addressing various aspects of the modern Lipetsk region territory development, as well as analyzing the reflection of global and regional historical processes in the territory under study.

Regarding the research of migration processes in the present-day Lipetsk region territory, a special place in this predominantly descriptive research belongs to the Territorial Body of the Federal State Statistics Service of the Lipetsk Region (Lipetskstat) that annually publishes statistical yearbooks that contain information on migration processes. However, there are no analytical materials in it. The problems of finding explanations for the migration situation in the Lipetsk region are usually covered in the framework of larger territory studies, for example, the Central Black Earth Region (Kurtsev, 1998; 2008a; 2008b; Porosenkov et al., 1986), or Central Russia. Studies of migration processes in the Lipetsk region are found in the works of G.R. Rostom (2007) and S.D. Zubkov (2000). At the same time, it can be said that there are no detailed studies on this topic, including historico-geographical specificity.

During the research, the authors proceeded from the fact that in different historical periods associated with the development of a particular territory, there were different migration trends determined by both internal and external factors. Ultimately, these trends could have an impact on the subsequent migratory behavior within the given territory. For the Lipetsk region, the key intermediate goal was to identify internal and external factors that have affected the migration processes in the region and to determine their correlation.

The research is based on the theory and methodology of regional historico-geographical analysis presented in the works of L.B. Vampilova (2010) based on historical and geographical periodization. While studying the process of the Lipetsk region territory development by man, the authors identified certain time intervals, that is, periods characterized by the dominance of certain migration trends and dominant factors that determined them. Thereafter, the authors analyzed those factors and determined the degree of their impact on the subsequent migratory behavior.

Understanding the fact that the modern Lipetsk region territory became inhabited sufficiently long ago, the authors start counting the migration process periodization from its development by the Slav populations, since currently there are relatively reliable sources that allow for analysis of migration processes at this time.

The early stage of the Lipetsk region territory development is associated with the Slav populations’ attempts to resettle thereto mainly motivated by relocation from old-cultivated regions in search of more fertile and unoccupied lands. In Everett S. Lee’s terms (1966), the factor attracting the Slav populations there was rich chernozem soils almost undeveloped agriculturally, while the expelling factor was the danger of nomad raids. Prior to the Mongol invasion, those two factors were counterbalancing, with the former beginning to gradually dominate as the Slavs consolidated on this territory. However, after the Mongols came to Russian lands, the situation changed dramatically and the expelling factor began to prevail.

Since the first half of the 15th century, part of the present-day Lipetsk region territory belonging to the Principality of Muscovy began to strengthen actively. Fortress cities Dankov, Talitsky Ostrog, Lebedyan, and Yelets appeared. At the same time, virgin lands were being developed. However, most of the modern Lipetsk region was part of the so-called “Wild Fields” referring to the lands that delimited the Muscovite state and the possessions of Crimean and Nogai Tatars who claimed this territory as well. To defend the southern frontiers of Muscovy, the construction of Belgorod defensive line begins in 1635, with its northern part passing through the modern Lipetsk region territory. The land was massively settled by so-called “servicemen” who served in fortresses. There is, however, an opinion that Russian population had inhabited the “fields” before the first towns appeared there, and that was it that subsequently established the basis for “servicemen” (Zagorovsky, 1969). According to V.P. Zagorovsky, “a part of Cossacks came “to the fields” for a short time, and then returned to their native lands, while others stayed there for a long time, forever” (Zagorovsky, 1969, p. 23). However, many locations did not have resident population. Anyone interested was recruited to the new fortresses. Thus, a letter to Chernava fortress read: “It is ordered to hire those willing to serve in Marksman and Cossack Troops” (Lyapin, 2011, p. 101). A fact testifying to “servicemen” settling the Belgorod line fortresses is a resettlement of Ukrainian Cossacks, “Cherkases”, thereto. The resettlement of Cherkases in the late 30’s of the 17th century is in particular accounted for the need to bolster the military service class on Russia’s border (Papkov, 1998, p. 34). D.I. Bagaley cites the data that in most Belgorod line towns “a certain number of Cherkases will be found” (Bagaley, 1887, p. 31). Thus, apart from Russian servicemen, Chernava fortress was also inhabited by Cherkases (Lyapin, 2011, p. 101). The foundation of Cherkassy village (Yeletsky district) and Cherkassy settlement (Izmalkovsky district) is associated with resettlement of 12 families of Cherkas army Cossacks thereto.

The resettlement proceeded according to the tsar’s decree, whereby it was determined in advance how many people of which ranks were subject to relocation. Not all resettlers left their native towns forever. Some were returning. The number of returnees in the 40s and 50s averaged 20-30% (Lyapin, 2011, p. 101-102). The population also moved within the Belgorod line fortresses. Thus, a decree was sent to Talitsky fortress (the village of Talitsa, Yeletsk district) ordering to relocate some of its inhabitants to the town of Korotoyak (Voronezh region) (Lyapin, 2011, p. 102).

From the late 16th century, more peaceful regions began to pass into the possession of large feudal lords, gradually becoming inhabited by peasant population. V.P. Zagorovsky (1969) notes a rapid growth of the population in the possession of the Romanov Boyars (in the vicinity of Lenino village, Lipetsk region). Estate managers brought peasants out of small landlords’ possessions; other peasants themselves went to be bonded by a feudal lord, especially from areas ravaged by the Poles.

Thus, in the late 16th – early 17th centuries, the present-day Lipetsk region territory was actively becoming inhabited by various kinds of migrants, primarily by the military. Those years were marked by a migration gain in most of the modern Lipetsk region territory.

With the Muscovite state consolidation, the present-day Lipetsk region territory ceased to be a border zone; the military share decreased as the peasant share increased (Glazyev, 1998, p. 26). Reforms of Peter the Great aimed at strengthening the army and building a fleet demanded major changes in the industrial organization. During that period, large manufacturing enterprises were established in the present-day Lipetsk region territory. In May 1703, construction of Lipskiye ironworks (the territory of the modern city of Lipetsk) commenced. Borinsky and Kuzminsky plants were situated in the vicinity thereof. In addition to metallurgical plants, “a cloth factory, a hattery, a hosiery mill, a tannery, boating workshops and other auxiliary plants are being built in the territory of the modern city of Lipetsk” (Martynov & Zhdanov, 1959, p. 43). People were needed in order to launch and maintain the manufacturing process. The personnel gap was filled by “assigning” them from the neighboring towns of Sokolsk, Romanov, Belokolodsk and even from Kiev (Martynov et al., 1995, p. 58). A transfer of such skilled professionals as blast-furnace foremen and blacksmiths was organized (Martynov et al., 1995, p. 54) from Voronezh. The construction of factories was supervised by Tula craftsmen. However, people were also relocating on their own initiative. Merchants began to move from the town of Romanov as early as in the 1710s (Vodarsky, 1996, p. 123). The fact that a significant part of the above-mentioned town population was transferred or moved independently to resettle in Lipskiye ironworks village played a pivotal role in those towns being disestablished (Vodarsky, 1996, p. 123). While registering the migration gain in industrial centers, one should note the characteristic tendency of “rural-to-urban” population movement, which corresponds to the stage of early transitional society, according to W. Zelinsky (1971). Additionally, there also was “urban-urban” migration with industry as the main attraction factor. Thus, up to 30,000 people were engaged in shipbuilding in Voronezh, exclusive of those assigned from neighboring towns (Rudakov, 1973, p. 65).

In the Peter years, displacement constraints were imposed on the population. An Imperial order of 1714 prohibited voivodes and governors from allowing people without passports to pass through provinces and governorates. Subsequently, two types of identification documents were introduced for aerarians: “subsistence” and “pass-through” letters (Ivanov, 2010, p. 130).

In the first half of the 19th century, there were hardly any migration processes in most of the modern Lipetsk region. Here is a characteristic observation on this point from the documents of 1848 on the Ryazan governorate population (part of it is now included in the Lipetsk region), whereby the population increase “has resulted solely from a [numerical] superiority of those born over those deceased, without resettlement and accession of land from other governorates" (Military Statistical Review of the Russian Empire, 1848, p. 25).

With the population development, a serious problem of arable land shortage was brewing, which prompted the authorities to search for a solution. The Emancipation reform of 1861 was the starting point in changing migration trends throughout the Russian Empire. A census of the Russian Empire population in 1897 revealed 3 million of the Central Black Earth Region residents who were migrants, or 23% of the enumerated population (Kurtzev, 2008a, p. 82).

The peasant population growth in Central Russia led to unfavorable socioeconomic processes. In Tambov governorate (part of which is now included in the Lipetsk region) in 1912, the surplus of workers was 2/3 of the population of working age (while being 3/4 and in farms and villages) – in total, over a million people (Ivanov, 1998, p. 115). Reforms of P.A. Stolypin were an effort to change the situation, whereby large-scale transfers of the surplus population to underdeveloped regions of the country began (Tokarev, 1998, p. 124). This accounted for a rapid migration stream beyond the Urals. 16,594 people from Tambov governorate alone left for Siberia in 1907, which was 8.3% above the consolidated figures for 1900-1906 (Tokarev, 1998, p. 124). In the period from 1907 to 1913, 106 thousand people relocated from Tambov governorate to Siberia (Ivanov, 1998, p. 115). At the same time, Siberian governors pointed to the need of resettlement constraints because of a lack of land (Tokarev, 1998, p. 124).

Despite rather powerful migration processes in the early 20th century, the demographic situation in the Central Black Earth Region villages did not change significantly.

A migration variety characteristic of that period was pilgrimage. A major center for regional pilgrimage, the town of Zadonsk, was involved in the process. Thus, according to A.N. Kurtsev, “prayer travelling” from 1861 onwards involved a lot of local peasants. The outbreak of the First World War was followed by a dramatic reduction in all forms of religious migration in the Central Black Earth provinces, while migration abroad stopped at all (Kurtzev, 2008b, p. 86).

An important event that intensified the migration processes in the Russian Empire, including within the modern Lipetsk region, was the First World War. Military conscription can be referred to as a variety of migration. 47.6% of able-bodied men were recruited from the rural areas of Tambov governorate. Also, during the war, the modern Lipetsk region territory became one of the resettlement centers for refugees (Kurtzev, 1998, p. 83). After a retreat of Russian troops in April-December 1915, far more people fled from the frontline area than at the beginning of the war. Some of them settled in the modern Lipetsk region territory. Thus, Lipetsk uyezd had hosted up to 15 thousand relocatees by the end of 1915. According to A.N. Kurtsev’s figures, there were massive influxes of refugees to the Central Black Earth Region in June-August 1915 that peaked in September-October and ended in November-December of the same year (Kurtzev, 1998, p. 83).

It should be noted that the official statistics normally took account of “common people” mostly. Public servants with the families and wealthy refugees in general as those not entitled to or not in need of “custody” were not subject to registration.

It is difficult to define the number of the First World War refugees having stayed in the territory of the Lipetsk region forever. The native population’s attitude towards refugees as their number increased was gradually changing from “very warm” to “mass eviction of refugees from apartments” (Kurtzev, 1998, p. 87). O. Okninsky reports interesting facts about the refugees who lived in Borisoglebsky uyezd of Tambov governorate in 1918-1920: “Accommodated in the uyezd villages, they were first welcomed by peasants sympathetically as their fellow peasants ... However, when the war started taking longer ... the native population’s attitude to the newcomers after sympathy became first indifferent to their fate, and then hostile” (Okninsky, 1998, p. 134).

After the October Revolution, attempts were made to implement a return of refugees to their homeland, but the Civil War events encumbered this; it was not until the 1920s when it could be done in a relatively stable and organized manner, although a considerable part tried to return home on their own.

The Revolution and the Civil War in Russia led to an extensive activation of migration processes related both to an outflow of the population (including abroad) and to an influx of people from large cities to the countryside. During that period, there was a pressure of expelling factors that affected the negative migration balance. In 1917-1922, the urban population of the USSR decreased by a quarter, its pre-revolutionary size was not retrieved until 1928. During that period, a migration variety previously not typical in the mass terms – the political one – was clearly traced. The questions “What to do?”, “To leave the estate or to stay?”, “Where to flee?” in one form or another sound from the pages of nobility memories with reference to the summer and autumn events of 1917, “… in late1917 – early 1918, often under dramatic circumstances, under the threat of arrest or murder, noble families were forced to abandon their ancestral estates and move to uyezd and provincial towns or to the capital. This relocation can be considered irrevocable migration, since with very rare exception the gone nobility never returned” (Barinova, 2017, p. 233). There is no exact information about the ratio and number of those leaving and remaining nobles. One can talk about two nobility migration streams both from provincial towns to the capital, hoping to become forgotten in the big city, and from large governorate and metropolitan cities to small towns of Siberia and the Urals on the calculation that their gentlemanship would go unnoticed in case of loss of documents or a name change (Barinova, 2017, p. 238).

From 1921, there was a rise in farming in Central Russia; at the same time, the cultivated land in the rest of the country continued to reduce. In this regard, labor migrants streamed thereto (including to the territory of modern Lipetsk region). Immigration to central Russian towns was faster than the absorption of newcomers by industry, hence a significant and even dangerous increase in the unemployment rate (from 1.2 to 1.6 million in the summer of 1924). Official documents voiced quite grave reservations about possible destabilization of the regime, and measures were being taken to prevent starving peasants from rushing to large cities and, first of all, to Moscow (Kulisher and Tolts, 2014, p. 169).

From the 1920s onwards, the government tried to actively develop programs aimed at regulating migration processes both within the country and overseas (Galas, 2011, p. 139). One of the prerequisites for the NEP introduction in late 1921 was to adjust domestic and international migration policies. With the beginning of industrialization, there was an outflow of population from rural to urban areas. In general throughout the country during the initial five-year industrial plans, the urban population increased by 6.5% per year (Zayonchkovskaya, 2000, p. 4). Due to creation of large industry facilities, the population of the town of Lipetsk increased more than threefold between 1926 and 1939, from 21.4 thousand people to 66.6 thousand people. At the same time, the population in other towns of the future Lipetsk region did not increase substantially (except for the town of Gryazi), which was accountable for the lack of large industry facilities.

What should not go unmentioned is a so-called forced migration that affected the modern Lipetsk region territory. The first large-scale deportations began in the early 1930s. There is no exact information on the number of so-called “kulaks” expelled from the Central Black Earth Regions to the northern regions of the country. According to P.M. Polyan, “the forced migrations of the 1920s, affecting tens of thousands of people in total, generally did not have a substantial demographic and economic impact” (Polyan, 2010, p. 111). At the same time, the dekulakization was followed by the repressions of the 1930s, which also made a significant contribution to forced migration, including in the modern Lipetsk region territory.

Like for the whole country, the period of the Second World War had a serious impact on migration processes within the presen-day Lipetsk region. Most of them were connected with an outflow of the population caused by military conscription, evacuation of part of the population with industrial enterprises, forced dispatch of the population from the occupied territories to Germany. At the same time, Lipetsk region had some features related to the fact that not its entire territory was under occupation, and also to the fact that for some time it was located in the so-called near-front zone, therefore, many towns and villages had hospitals that admitted wounded Red Army soldiers. Many settlements accepted evacuatees from other regions. Thus, there are documents regarding, among other things, the accommodation of evacuated population from Nikolsky district of the Oryol region amounting to 10,000 people in villages of Dobrovsky district in 1942 (Lipetsk Region during the Great Patriotic War, 2005, p. 90). As for forced evacuations connected with the population dispatching for forced labor in Germany, according to the documents they were a mass phenomenon in the occupied territories. 158 people were dispatched from the Terbunsky district territory (Lipetsk Region during the Great Patriotic War, 2005, p. 107), 150 male collective farm workers (Lipetsk Region during the Great Patriotic War, 2005, p. 103-105) were dispatched from the Volynsky district territory (currently a part of the Stanovlyansky district of the Lipetsk region), 72 people from the Stanovlyansky district territory (Lipetsk Region during the Great Patriotic War, 2005, p. 114-115), etc.

In the post-war period, the population in the region gradually begins to recover, including due to a migration gain in such industrially developed cities as Lipetsk, whose population doubled compared to 1939. The total migration gain of 7,800 people in the city of Lipetsk was recorded in 1954 (Anichkina et al., 2013, p. 67). In general, migration was typical of the region. Thus, in 1954, the year of the Lipetsk region formation, a total migration gain of 9,544 people was recorded (Lipetsk Region. 60 Years. Anniversary Statistical Collection, 2013, p. 38).

A trend characteristic of that time was “rural-to-urban” migration. During the 20th century, the urban population of both Russia and the USSR increased more than 10-fold. Approximately a half of its growth occurred in the 1960s and 1980s – every other new Russian citizen was a migrant at that time. Migration ensured the urban population growth in Russia by 8 million people in the 60s, by the same number in the 70’s and by 5.5 million in the 80’s. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed, two-thirds of its residents and three-quarters in Russia alone were urban dwellers (Zayonchkovskaya, 2000, p. 5). The pivotal motives for urbanization were economic. Throughout the period, a positive migration balance was characteristic of the Lipetsk region, with a downward trend from 9,600 people to 2,837 in 1990 (Lipetsk Region. 60 Years. Anniversary Statistical Collection, 2013, p. 38). Urbanization continued to be an overall trend, whereby the largest migration gain in Lipetsk (10.2 thousand people) in 1965 was reduced to be 3.1 thousand in 1989 (Anichkina et al., 2013, p. 67). At the same time, during the period under review, the entire Central Black Earth Region was characterized by a negative migration balance (1,436,800 people in the 1960s, 372,500 people in the 1970s, 142,000 people in 1979-1988 (Zayonchkovskaya, 2000, p. 7), which is accounted for the significance of Lipetsk as a large industrial center capable of attracting labor migrants.

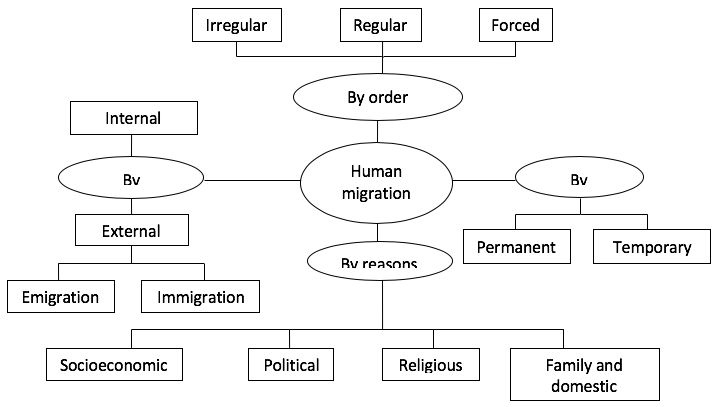

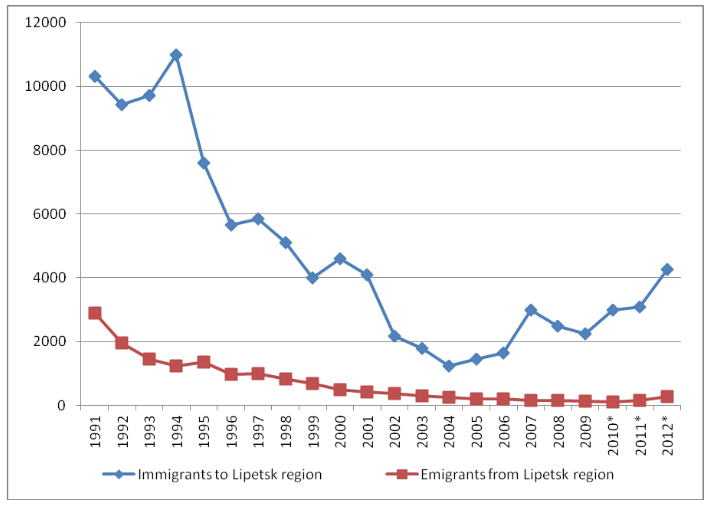

The Soviet Union collapse led to major changes in the migration processes, including in the Lipetsk region. The number of migrants to the territory of the region peaked in 1994 (14,529 people). Migration became increasingly forced and spontaneous: refugees and internally displaced persons appeared in the migrant structure. The direction of migration flows altered – from the border lands to the central regions of the country with no lack of population. The Russian-speaking population of former Soviet lands began to leave their homes and streamed to their historical homeland. Thus, the reverse stream was no longer internal but external migration (Shurupova, 2006, p. 68). Population growth in the last decade of the 20th century was ensured by population migration to the territory of the region from former republics of the USSR, “flash spots” of the country, “demanding” areas in the Far North, Siberia, and the Far East, etc. (Figure 2). As long ago as in 1989, the urban population increased due to a migration gain of 8.4 thousand people, which is 2.4 thousand more than in 1985. First of all, intraregional migration from rural to urban areas was taken into account therein. In the total migration gain of 1989, it was 50%. Nevertheless, from 1994 onwards, the migration balance was positive for a long time, continued to decline steadily and became negative in 2004 (-167 people). Changes in the intensity of the migratory influx into the Lipetsk region generally correspond to nationwide changes: a surge in the early 1990s followed by a fall. In the same period, there was a reduction in the number of emigrants from the region.

Currently, the region is characterized by population migration (including commutation) to Moscow and the Moscow region, as well as commutation of the suburbs of large cities.

The number of immigrants after 2004 started to increase by degrees; however, the crisis that affected the country in 2008 reduced the intensity of the migration inflow to the Lipetsk region. Emigration processes remained stable in 2004-2008. Not until after 2009 there was a surge in the activity of immigrants and emigrants of the Lipetsk region. This led to a negative migration balance up to -849 people in 2011. In 2012, the migration gain slightly increased to 579 people.

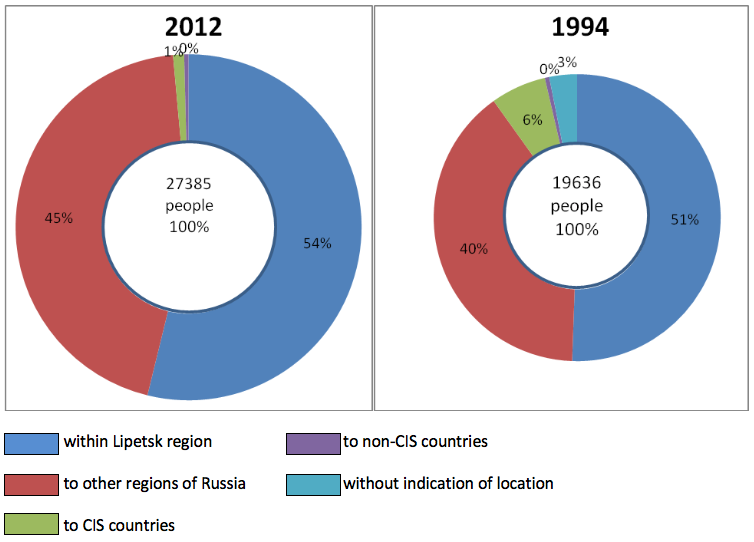

Figure 2

Migration of the Lipetsk region population

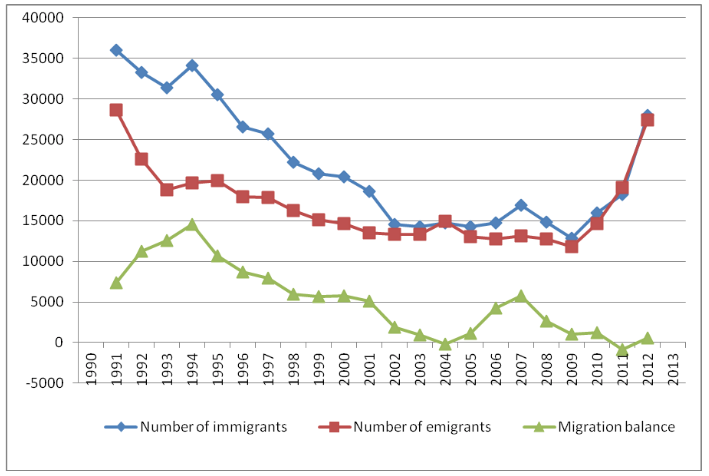

The migration turnover (the aggregate number of immigrants and emigrants) in 2012 was 55.3 thousand people. A total of 27,964 people arrived in the Lipetsk region (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Dynamics and structure of immigration in the Lipetsk region

The emigrant structure is markedly different from immigrant structure (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Dynamics and structure of emigration from the Lipetsk region

The essential part of able-bodied population emigrates from the Lipetsk region to other regions of the Russian Federation. The outflow of able-bodied population is partially compensated by international migrants, most of them coming from the CIS countries.

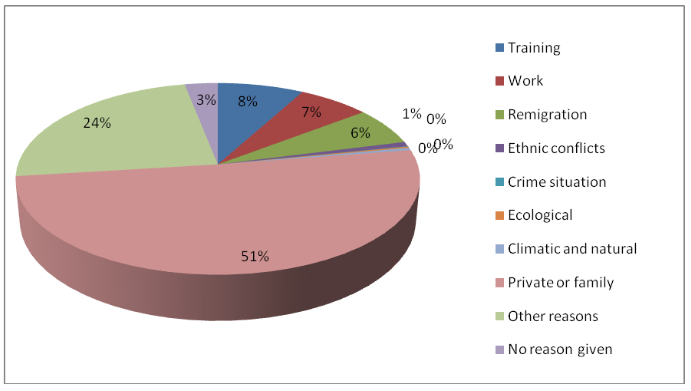

The reasons for migration vary (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Distribution of immigrants aged 14 and over by relocation reasons in 2012

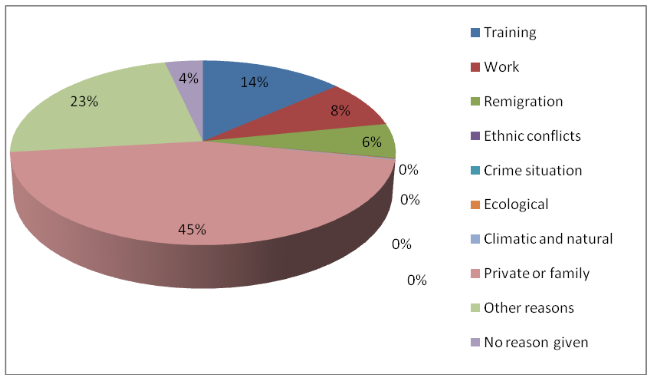

6% re-emigrated from the Lipetsk region. 23% indicated other reasons for emigration (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Distribution of emigrants aged 14 and over by relocation reasons in 2012

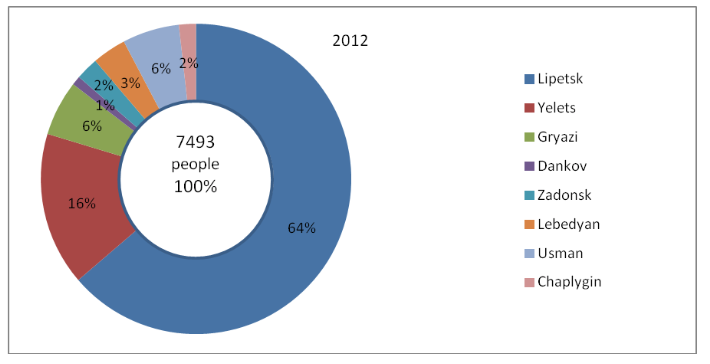

Intraregional migration contributed to an increase in the number of urban residents due to rural residents by 818 people (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Intraregional migration to the towns of the Lipetsk region

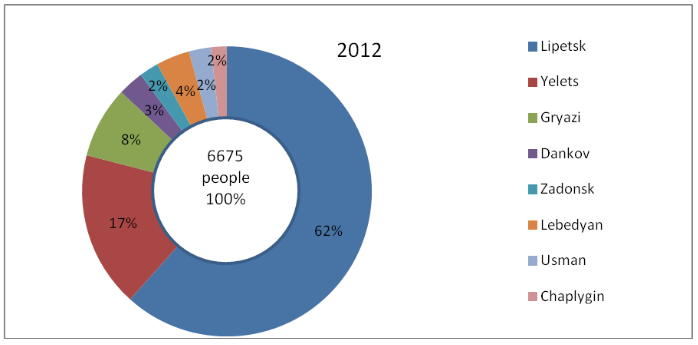

6,675 people left the urban area in 2012 (Figure 8). The structure of emigration from the towns of the Lipetsk region is not much different from immigration to them.

Figure 8

Intraregional migration from the towns of the Lipetsk region

Figure 9 shows an inverse relationship between the number of immigrants and economic stabilization of in the CIS and Baltic countries.

Figure 9

Migrational exchange of the Lipetsk region

with the CIS and Baltic countries

* Data for the CIS countries

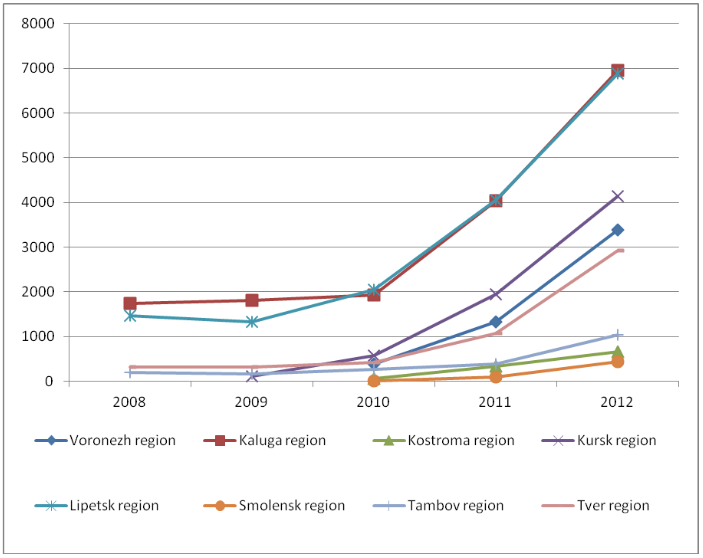

An important role in the migration gain of the population from former USSR republics was played by a state program to assist voluntary resettlement of compatriots living abroad to the Russian Federation, adopted in 2006 (Figure 10).

Figure 10

The number of participants in the State program to assist voluntary

resettlement to the constituent entities of the Russian Federation

In addition to those arriving in the Lipetsk region under this program, the influx of temporary labor migrants from the CIS countries, which in many cases assumes the character of permanent illegal migration, is increasing.

Analysis of migration balance in the Lipetsk region territory has shown that since 2013 the number of incomers to the Lipetsk region has exceeded the number of those who leaving (+2,127 people). This process intensified after the outbreak of a conflict in the southeast of Ukraine in 2014, when the Lipetsk region in particular provided emergence shelter to displaced persons. In 2016, the positive migration balance peaked within the last few years to reach 4,572 people. However, as early as in 2017 it was negative again (-646), which can partly be accounted for an economic downturn in the region.

Summing up the research findings, one may talk of the fact that in the periods indicated, the factors determining the migration trends were dominated both by general trends characteristic of all regions of the world, namely “rural-to-urban” migration flows, and specific factors characteristic of the country as a whole (the negative migration balance associated with the Revolution and the Civil War, the migration gain of the 1990s, etc.), as well as local factors determined by the specifics of the economic complex of the region.

Anichkina, N.V., Belyaeva, L.N., Zubkova, V.L., Klimov, D.S., Litvinenko, A.K., et al. (2013). Lipetsk. View through the Centuries: Historical and Geographical Statistical Publication. Lipetsk: Lipetskstat.

Bagaley, D.I. (1887). Essays on the Moscow State Steppe Outskirts Colonization History. Мoscow: University Printing House (M. Katkov).

Barinova, E.P. (2017). Provincial nobility during the Civil war. XX Century and Russia: Society, Reforms, Revolutions, 5, 230-238.

Galas,M.L.(2011). State mechanism of regulating labor immigration and return migration in USSR in 1920s. Authority, 3, 139-146.

Glazyev, V.N. (1998). Accommodation and service of voivodes in the Black Earth region in the late XVI century. In Proceedings of the VI Scientific Conference “Problems of Historical Demography and Historical Geography of the Central Black Earth Region and Russia’s West” (pp. 25-27). Lipetsk, Russia: Lipetsk State Pedagogical Institute.

Iontsev, V.A. (1999). International Migration: Theory and History of Studying. Moscow: Dialogue – Moscow State University.

Ivanov, A.A. (1998). Agrarian overpopulation in the Central Black Earth region of the early XX century and its consequences. In Proceedings of the VI Scientific Conference “Problems of Historical Demography and Historical Geography of the Central Black Earth Region and Russia’s West” (pp. 114-117). Lipetsk, Russia: Lipetsk State Pedagogical Institute.

Ivanov, S.K. (2010). Legal adjustment of the control system for the migratory processes in the Russian Empire of the XVII-XVIII centuries. Buletin of the Chuvash State University, 2, 129-133.

Kulisher, А.М., & Tolts, М. (2014). The theory of the movement of peoples and the civil war in Russia. Preface and comments by Mark Tolts. Demographic Review, 1(3), 158-173.

Kurtzev, A.N. (1998). Refugees of the First World war in the Central Black Earth region in 1914-1917. In Proceedings of the VI Scientific Conference “Problems of Historical Demography and Historical Geography of the Central Black Earth Region and Russia’s West” (pp. 80-88). Lipetsk, Russia: Lipetsk State Pedagogical Institute.

Kurtzev, A.N. (2008a). Historical variety of population's migration of the Central Black Earth region in 1861-1917. RUDN Journal of Russian History, 3, 82-92.

Kurtzev, A.N. (2008b). Religious migrations of population of the Central Black Earth region in 1861-1917. Izvestia: Herzen University Journal of Humanities & Science, 81, 81-87.

Lee, E. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3, 47-57.

Lipetsk Region during the Great Patriotic War. (2005). Lipetsk.

Lipetsk Region. 60 Years. Anniversary Statistical Collection. (2013). Lipetsk: Lipetskstat.

Lyapin, D.A. (2011). History of Yelets Uyezd in the Late XVI-XVII Centuries. Tula: Grif & Е.

Martynov, A.F., Polyakov, V.B., Klokov, A.Y., Lanikin, V.D., & Konyshev, Yu.F. (1995). Chrestomathy on the Lipetsk Region History. Lipetsk: Koda.

Martynov, A.F., & Zhdanov, V.M. (1959). From the Past of Lipetsk Region. Lipetsk: Book Publishing House.

Military Statistical Review of the Russian Empire. Volume VI. Great Russian provinces. Part 3. Ryazan province. (1848). Saint Petersburg: General Staff Printing House.

Okninsky, A.L. (1998). Two Years among the Peasants. Мoscow: Russkiy put’.

Papkov, A.I. (1998). Ordering of the Ukrainian immigrants service in the territory of the Belgorod line in the 40-es of XVII century. In Proceedings of the VI Scientific Conference “Problems of Historical Demography and Historical Geography of the Central Black Earth Region and Russia’s West” (pp. 34-36). Lipetsk, Russia: Lipetsk State Pedagogical Institute.

Plisetskiy, E.L. (2003). Modern migration processes in Russia. Geography, 37. Retrieved from http://geo.1september.ru/article.php?ID=200303705

Polyan, P.M. (2010). Forced migration and population geography. Universe of Russia, 8(4), 102-113.

Porosenkov, Yu.V., Valyaev, V.I., Dyakovskaya, V.R., & Kyryanchuk, V. E. (1986). The Central Black Earth Region: Economy and Population. Voronezh: Publishing House of the Voronezh State University.

Ravenstein, E. (1876). The Laws of Migration. London.

Rostom, G.R. (2007). Territorial differences of demographic characteristics in the Lipetsk region. In Materials of the Interregional Scientific and Practical Conference “Demographic Factor in the Socio-Economic Development of the Lipetsk Region”. Lipetsk.

Rudakov, L.E. (1973). Following the Footsteps of Legends. Essays on the History of the Lipetsk Region Cities and Architecture Monuments. Voronezh: Central Black Earth Book Publisher.

Rybakovsky, L.L. (2003). The Population Migration (Theory Questions). Мoscow: Institute of Socio-Political Research of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Shurupova, A.S. (2006). Migrants Labor Potential Management in the Agricultural Sector of the Region's Economy. Lipetsk: Lipetsk Newspaper.

Tokarev, N.V. (1998). Regulation of migration movement over the Urals in the period of Stolypin agrarian reform. In Proceedings of the VI Scientific Conference “Problems of Historical Demography and Historical Geography of the Central Black Earth Region and Russia’s West” (pp. 124-127). Lipetsk, Russia: Lipetsk State Pedagogical Institute.

Vampilova, L.B. (2010). Regional historical and geographical analysis theory. Pskov Regional Journal, 10, 129-140.

Vasilenko, P.V. (2013a). Foreign human migration theories. Pskov Regional Journal, 16, 36-42.

Vasilenko, P.V. (2013b). Geographical aspects of population migration research. Bulletin of the Pskov State University. Series "Natural and Physical and Mathematical Sciences", 2, 105-111.

Vodarsky, Ya.E. (1996). Problems of essence, time and place of foundation of cities and the emergence of Lipetsk. In Lipetsk - History Beginning. Lipetsk, pp. 80-131.

Zagorovsky, V.P. (1969). Belgorod Line.Voronezh: Publishing House of the Voronezh University.

Zayonchkovskaya, Zh.А. (2000). Migration of the USSR and Russia’s population in the XX century: evolution through cataclysms. Problems of Forecasting, 4, 1-15.

Zelinsky, W. (1971). The Hypothesis of the mobility transition. Geographical Review, 61, 219-249.

Zubkov, S.D. (2000). Territorial organization of reproduction of the population of the Lipetsk region (Candidate thesis, Voronezh State Pedagogical University, Russia).

1. Lipetsk State Pedagogical P. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky University, Lipetsk, Russian Federation, E-mail: geodsklim@mail.ru

2. Lipetsk State Pedagogical P. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky University, Lipetsk, Russian Federation