Vol. 39 (Number 39) Year 2018 • Page 18

Beatrice AVOLIO 1; Rosalyn ACCOSTUPA 2; Ronar BERMÚDEZ 3; Roxana CHÁVEZ 4; Ronald MONTES 5

Received: 09/04/2018 • Approved: 21/05/2018

ABSTRACT: The purpose of the study is to qualitatively analyze women microentrepreneurs with good and bad history payment in microfinance institutions, as well as to look for the variables that can be used as differentiators between both groups and can be included as a part of the credit assessment process in microfinance institutions. The study has identified the variables that allow discerning between women microentrepreneurs with good and bad payment history. The study proposes using certain variables in the credit analysis process of women microentrepreneurs at microfinance institutions. |

RESUMEN: El objetivo de este estudio es realizar un análisis cualitativo de las microempresarias con historial de pago bueno y deficiente en instituciones microfinancieras y buscar variables que se puedan usar como diacríticos entre amos grupos para incluirlas como parte del proceso de evaluación crediticio en las microfinancieras. El estudio identificó las variables que permiten discernir entre las mujeres microempresarias con buen y mal historial de pago. El estudio propone el uso de determinadas variables dentro del proceso de análisis crediticio de las microempresarias en las entidades microfinancieras. |

The past few years have been characterized by the increase of the participation of women in the economic activity. The International Labour Organization (ILO) (2016a) estimated that the global female participation rate in 2015 was 49.6%. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the female participation rate in the economic activity has had a steady increase (48.5% in 2006 to 49.6% in 2015), while the male participation rate decreased in the same period (75.5% in 2006 to 75.1% in 2015) (ILO, 2016). With regard to the global entrepreneurial activity, it is estimated that women own and control more than one third of the companies (including self-employed or independent workers) (ILO, 2015). Particularly, in Latin America and the Caribbean, women play an important role in entrepreneurship. The female total entrepreneurial activity (TEA [6]) rate is 17.8%. It is the highest rate reported in the world (Kelley, Singer, & Herrinfton, 2016).

Female entrepreneurship in Latin America is mainly related to micro and small-sized enterprises. According to GTZ, WB, & BID (2010), as the size of the companies grows, the percentage of women-owned businesses decreases. In Argentina, 33% of women-owned businesses are microenterprises, 26% are small and 21% are medium-sized; in Bolivia, 38% are microenterprises, 31% are small and 28% are medium-sized; in Brazil, 38% are micro, 31% are small, and 29% are medium in size; in Ecuador, 41% are microenterprises, 18% are small-sized, 14% are medium-sized; in Honduras, 50% are microenterprises, 24% are small, 23% are medium-sized; in Mexico, 37% are microenterprises, 20% are small, 12% are medium-sized; in Peru, 44% are microenterprises, 20% are small and 12% are medium-sized; in Uruguay, 38% are microenterprises, 27% are small and 25% are medium-sized enterprises.

Valenzuela (2005, cited by Heller, 2010) stated that, in Latin America, women involved in the development of microenterprises constitute a strong source of income for their households. Women are concentrated in this sector because they have the possibility to easily start a business as a result of the few barriers in terms of requirements. These are: (a) education level, (b) legal requirements, and (c) required capital. Another reason why women are concentrated in this sector is the flexibility of this type of organization (sometimes the activity is performed at home and requires less investment), which enables them to combine paid work with family activities and tasks. Women microentrepreneurs are characterized by: (a) using less labor and physical capital; (b) having low levels of human capital; (c) concentrating on few economic sectors, such as manufacturing, services and trade; (d) having less chances of getting training and business development services, since these are directed towards men; (e) even though they still have unequal access to credit in comparison with men, women are more afraid of applying for a loan; they don’t usually resort to these options and use more informal funding sources; and (f) having assets of lesser value than men, which limits the access to a bank credit because they require more collaterals (Program Promoting Gender Equality [GTZ] Et al., 2010).

According to the Program Promoting Gender Equality (GTZ et al. 2010), the concentration of women in activities related to micro and small-sized enterprises is due to: (a) a small number of women don’t have the necessary business skills to manage a larger company; (b) the growth and good results may be hampered by the barriers that affect more women than men, such as child-care, household responsibilities, access to finance, regulatory burden, and market conditions; and (c) women prefer to have smaller businesses to efficiently divide their time at work and at home.

Historically, it is known that the access to external funding sources of micro and small-sized enterprises owners in developing countries has been minimal or non-existent, with the exception of the following sources: (a) friends, (b) family members, and (c) informal lenders. This has improved in the last 20 to 30 years as a result of the expansion and the development of microfinance; thus, the unequal access to funding sources between men and women has been reduced (Powers & Magnoni, 2010). In spite of this, women have had greater difficulty to have access to credit in Latin America, since the access to funding sources is mostly available for solid and larger companies. According to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization [UNIDO] (1995, cited by Powers & Magnoni, 2010), women face more difficulties to obtain financial products due to the discriminatory attitudes of financial institutions. This can remain in the institutional lending criteria or it can be the bank preconceptions in regard to women-owned businesses, because women are mainly engaged in the informal economy, their businesses are generally small, they have fewer assets to serve as collaterals, and they are less likely to have properties in their own name to offer them as collaterals (World Bank, 2006, cited by Powers & Magnoni, 2010, p. 12).

The Microcredit Summit Campaign report (2005, cited by McCarter, 2006) stated that female participation in microfinance approximately represent the 83% of all the reported customers and women have proven to be the better payers that men over time. In addition, in accordance with Microfinance Information Exchange (2009), the companies characterized as a non-bank financial intermediary (NBFI) registered a total of 79.1% women borrowers. Pedroza (2011) also stated that, in Latin America and Caribbean, the access of women microentrepreneurs to microcredit is averagely 59.8%. An analysis by region reported that Mexico leads the region (88%), followed by the Caribbean (70%), Central America (59%), and South America (56.1%).

Studies show a high global compliance rate of payments made by women in the microfinance sector. Hossain (1998) found that, in Bangladesh, 81% of women microentrepreneurs had no problem to pay their microcredits; on the other hand, the male ratio is 74%. In Malawi, Hulme (1991) found that 92% of women microentrepreneurs pay on time their loans. In Malaysia, Gibbons & Kasim (1991) found that 95% of women microentrepreneurs also pay their loans on time. Finally, in Guatemala, Kevane and Wydick (2001) found that group credits formed only by women had better results compared to the group credits formed by men. Research studies conducted in 350 microfinance institutions (MFI) in 70 countries over 11 years found that women are better payers than men because they invest in businesses that generate a faster return on investment, they use more cautious and conservative investment strategies and, therefore, they manage their obligations better. The fact of having fewer opportunities for funding sources encourages them to fulfill their payments (D'Espallier, Guerin & Mersland, 2011). A study conducted in six Latin American countries (Guatemala, Nicaragua, Colombia, Bolivia, Mexico and Peru) found that “women have proved to be reliable debtors with payment rates higher than those of men, which has strengthened their profile before MFIs and other credit institutions” (Powers & Magnoni, 2010, p. 1). In Guatemala, Kevane and Wydick (2001) found that group credits formed only by women had better results compared to the group credits formed by men. Portocarrero, Trivelli and Alvarado (2002) pointed out that in the Institute for Peasant Trade (IFOCC), which operates in Peru (Cusco), 30.8% of delinquent debtors are women, while 41.8% of non-delinquent clients are women. D'Espallier, Guerin, and Mersland (2011) stated that the factors that influence women to be better payers are: (a) the type of businesses allows a more rapid return on investment in order to comply with the credit obligations and (b) women have less access to credit than men; consequently, they are more concerned about continue having it. The latter depends on women having to make the decision to pay, and not being subject to the men’s decision.

The high female participation in microcredit has interested MFIs in order to improve the credit check criteria for this segment of borrowers, to understand better the target segment, and to improve the processes of credit allowance. In this sense, the purpose of the study is to qualitatively analyze women microentrepreneurs with good and bad history payment in microfinance institutions, as well as to look for the variables that can be used as differentiators between both groups and considered as part of the credit assessment process in microfinance institutions.

Microfinance refers to the “provision of financial services to low-income people, especially the poor” (Delfiner, Pailhe & Peron, 2006, p.4). The efforts of microfinance to make financial services accessible had positive results in terms of scope and number of clients (Gutierrez, 2009). The entities that perform this action are called microfinance institutions (MFIs). The modern development of MFIs occurred in 1970s with two pioneering experiences at Grammeen Bank and Accion (in Bangladesh and Brazil, respectively). These institutions agreed that it is necessary to acknowledge the development problems and the opportunity that microcredits provide, in order to face the funding of microeconomic development. Particularly, Muhammad Yunus, creator of the Grameen Bank, recognized that poor people could improve their situation if a small financial contribution is given to them as capital, which would be later returned maintaining a surplus. The system implemented by Yunus includes elements such as the proximity to customers, elimination of usual guarantees, introduction of hard work, self-esteem and self-motivation, preference for women because they improve the family condition, lower default rates, among other financial aspects. The positive results obtained by financial institutions expanded the use of these elements to a larger extent. Since 1990s, microfinance programs are part of the efforts to achieve the development goals and the fight against poverty (Gutierrez, 2009).

Microfinance institutions “provide poor people, who are ordinarily left out of the formal financial sector, with access to a range of financial services allowing the power of choice and the ability to change one's life for better.” (McCarter, 2006, p.355). The objective is “to give low income people an opportunity to become self-sufficient by providing a means of saving money, borrowing money, and insurance.” (Veeramani, Selvaraju & Ajithkumar, 2009, p.84). The main microfinance guarantee mechanisms are: personal reputation and prestige; joint and several guarantee; mutual guarantee; the active follow-up of the projects that will be funded; social pressure; the pledge of certain goods with an important symbolic value; personal guarantees in general, and common legal actions (Cortes, 2008).

Microcredit is one of the services provided by finance institutions. Microcredits are programs that provide small loans to low-income people or microentrepreneurs to allow them to start up self-employment projects that will help them to support their families and themselves, and to improve their standard of living (CGAP & Micro Credit Summit, 1997, cited by Heller, 2010; Fuertes & Chowdhury, 2009, cited by García & Diaz, 2011, Lacalle, 2006, 2008, cited by García & Diaz, 2011). In this way, microcredits try to eliminate “the lack of understanding” and the financial exclusion of microenterprises, families, or people who are at risk of being excluded from the banking system and don’t have a credit history or collaterals in order to be eligible for funding. Microcredits simplify the access of this population to bank and financial credit in optimal conditions (Cortés, 2008).

Microcredit is characterized by the grant of small loans to be paid in the short term, sometimes even less than a year. There is no need for guarantees, as requested by traditional banking. The credit rating methodologies are different and more focused on the customer's willingness to pay, the speed and flexibility of the method of payment, and the collection of loans (Rayo et al., 2010). Microcredit substantially differs from traditional credit because the latter aims to obtain profitable benefits. It is directed towards medium or high income companies and individuals. The amounts are high and offered in the long term with market interest rates. Finally, these traditional loans need collaterals, formal documentation, and are mainly paid off on a monthly basis (Torre, Sainz, Sanfilippo & López, 2012).

Microfinance institutions are also subject to risks. Default is a risk that can be defined as the “delay of a minimum of 30 days from the due date of at least one installment of the microcredit granted to a particular client.” (Rayo et al., 2011.p. 24). The possibility of non-payment by customers is also known as credit risk or default (Band & Garza, 2014). The credit risk represents monetary losses deriving from the changes in a client’s credit quality. This can be divided into expected and unexpected losses (Gieseck, 2004, cited in Band & Garza, 2014). Credits are offered after an evaluation using the credit scoring technique. This technique is included in the “New Capital Accord” approved in 2004 by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. This international agreement states that finance and microfinance institutions attached to the Committee are required to establish measurement models to discriminate the clients according to their risk profile (Rayo, Lara & Camino, 2010).

Credit rating is an assessment system that measures the applicant’s credit capacity based on their profile in comparison with the profiles of previous applicants. The scoring methods are used to perform credit operations based on payment compliance. For this purpose, statistical operations are used to predict future risks (Amat, 2014). “Credit scoring is a technique that classifies the clients who apply for a loan and measures the credit risk inherent in its grant.” (Banda & Garza, 2014, p.6). According to Banda & Garza (2014), the first approach to the classification was introduced by Fisher (1936). Subsequently, Durand (1941) adapted Fisher’s model to classify applicants in good and bad applicants based on their previous credit record. Authors, such as Myer and Forgy (1963), Orgler (1970), Bierman and Hausman (1970), and Hand and Henley (1997) developed credit scoring models. Escalona (2011) mentioned that the first credit scoring model for MFIs was developed by Viganó (1993), which was a discriminant analysis model developed in an institution in Burkina Faso, with a sample of 100 credits and 53 variables. According to Schreiner (2000), there are also case studies in Latin America. Experiments in Bolivia and Colombia showed that statistical evaluations can improve the risk assessment. Miller and Rojas (2005) performed the credit scoring of SMEs in Mexico and Colombia, while Milena et al. (2005) studied MFIs in Nicaragua.

Parametric and non-parametric models applied in the development of statistical and non-statistical methods are used in credit scoring models. Among the credit scoring models are: discriminant analysis, linear probability models, probit, logit, linear programming, and neural networks (Kim, 2005). The credit scoring does not replace the traditional process of credit that includes the credit advisors’ knowledge about the customer (Schreiner, 2000). The credit advisors’ role is essential in microfinance because they verify the applicants’ conditions and understands their business operations. This allows the credit advisor to qualitatively judge the microentrepreneurs’ ability to pay (Escalona, 2011). Some of the criticisms about the credit assessment as a whole are that credit scoring is difficult to develop due to the scarce literature. It is noted that a comprehensive loan record database is needed in order to analyze the payers’ behavior; however, MFIs do not register information of the loans applications that were rejected and didn’t pass the analyst’s standard assessment. Hence, there is only information of approved applications (Escalona, 2011). The lack of information becomes a problem when developing systems for measuring microcredit risk. It is also noted that the credit advisor’s decision somehow includes subjectivity.

The prediction of microfinance risks should be approached with different variables or forms to overcome the database limitations (Rayo, Lara & Camino, 2010). Particularly, the gender variable is not widely used in the credit check process. At the financial level, MFI consider women as a more reliable group in comparison with their male peers because they are more responsible and sensitive to social reputation, they have less delinquency and bankruptcy rates, a greater balance of investment, saving capacity, and suggest self-employment projects with better risks (Cortes, 2008). However, women are the weakest sector in impoverished societies. They don’t have financial autonomy or decision-making capacity in regard to the family income. Hence, this turns into a process of financial exclusion and mistrust by the MFIs (Cortes, 2008). This is why it is important to include variables with a cross-sectional gender analysis to discern the good payers from the bad payers.

Although several credit scoring techniques have been studied to improve the credit assessment process in microfinance, no study has considered women microentrepreneurs and their special characteristics. In this scenario, it is essential to research the general knowledge of female good and bad payers’ life expectations, their business management skills, funding management, and each one of the variables included in these concepts. These elements could be included in one of the credit check process phases in order to understand the most relevant and differentiating characteristics of good and bad payers in a survey. This will be useful as filters or variables in a risk rating.

Microfinance refers to the “provision of financial services to low-income people, especially the poor” (Delfiner, Pailhe & Peron, 2006, p.4). The efforts of microfinance to make financial services accessible had positive results in terms of scope and number of clients (Gutierrez, 2009). The entities that perform this action are called microfinance institutions (MFIs). The modern development of MFIs occurred in 1970s with two pioneering experiences at Grammeen Bank and Accion (in Bangladesh and Brazil, respectively). These institutions agreed that it is necessary to acknowledge the development problems and the opportunity that microcredits provide, in order to face the funding of microeconomic development. Particularly, Muhammad Yunus, creator of the Grameen Bank, recognized that poor people could improve their situation if a small financial contribution is given to them as capital, which would be later returned maintaining a surplus. The system implemented by Yunus includes elements such as the proximity to customers, elimination of usual guarantees, introduction of hard work, self-esteem and self-motivation, preference for women because they improve the family condition, lower default rates, among other financial aspects. The positive results obtained by financial institutions expanded the use of these elements to a larger extent. Since 1990s, microfinance programs are part of the efforts to achieve the development goals and the fight against poverty (Gutierrez, 2009).

Microfinance institutions “provide poor people, who are ordinarily left out of the formal financial sector, with access to a range of financial services allowing the power of choice and the ability to change one's life for better.” (McCarter, 2006, p.355). The objective is “to give low income people an opportunity to become self-sufficient by providing a means of saving money, borrowing money, and insurance.” (Veeramani, Selvaraju & Ajithkumar, 2009, p.84). The main microfinance guarantee mechanisms are: personal reputation and prestige; joint and several guarantee; mutual guarantee; the active follow-up of the projects that will be funded; social pressure; the pledge of certain goods with an important symbolic value; personal guarantees in general, and common legal actions (Cortes, 2008).

Microcredit is one of the services provided by finance institutions. Microcredits are programs that provide small loans to low-income people or microentrepreneurs to allow them to start up self-employment projects that will help them to support their families and themselves, and to improve their standard of living (CGAP & Micro Credit Summit, 1997, cited by Heller, 2010; Fuertes & Chowdhury, 2009, cited by García & Diaz, 2011, Lacalle, 2006, 2008, cited by García & Diaz, 2011). In this way, microcredits try to eliminate “the lack of understanding” and the financial exclusion of microenterprises, families, or people who are at risk of being excluded from the banking system and don’t have a credit history or collaterals in order to be eligible for funding. Microcredits simplify the access of this population to bank and financial credit in optimal conditions (Cortés, 2008).

Microcredit is characterized by the grant of small loans to be paid in the short term, sometimes even less than a year. There is no need for guarantees, as requested by traditional banking. The credit rating methodologies are different and more focused on the customer's willingness to pay, the speed and flexibility of the method of payment, and the collection of loans (Rayo et al., 2010). Microcredit substantially differs from traditional credit because the latter aims to obtain profitable benefits. It is directed towards medium or high income companies and individuals. The amounts are high and offered in the long term with market interest rates. Finally, these traditional loans need collaterals, formal documentation, and are mainly paid off on a monthly basis (Torre, Sainz, Sanfilippo & López, 2012).

Microfinance institutions are also subject to risks. Default is a risk that can be defined as the “delay of a minimum of 30 days from the due date of at least one installment of the microcredit granted to a particular client.” (Rayo et al., 2011.p. 24). The possibility of non-payment by customers is also known as credit risk or default (Band & Garza, 2014). The credit risk represents monetary losses deriving from the changes in a client’s credit quality. This can be divided into expected and unexpected losses (Gieseck, 2004, cited in Band & Garza, 2014). Credits are offered after an evaluation using the credit scoring technique. This technique is included in the “New Capital Accord” approved in 2004 by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. This international agreement states that finance and microfinance institutions attached to the Committee are required to establish measurement models to discriminate the clients according to their risk profile (Rayo, Lara & Camino, 2010).

Credit rating is an assessment system that measures the applicant’s credit capacity based on their profile in comparison with the profiles of previous applicants. The scoring methods are used to perform credit operations based on payment compliance. For this purpose, statistical operations are used to predict future risks (Amat, 2014). “Credit scoring is a technique that classifies the clients who apply for a loan and measures the credit risk inherent in its grant.” (Banda & Garza, 2014, p.6). According to Banda & Garza (2014), the first approach to the classification was introduced by Fisher (1936). Subsequently, Durand (1941) adapted Fisher’s model to classify applicants in good and bad applicants based on their previous credit record. Authors, such as Myer and Forgy (1963), Orgler (1970), Bierman and Hausman (1970), and Hand and Henley (1997) developed credit scoring models. Escalona (2011) mentioned that the first credit scoring model for MFIs was developed by Viganó (1993), which was a discriminant analysis model developed in an institution in Burkina Faso, with a sample of 100 credits and 53 variables. According to Schreiner (2000), there are also case studies in Latin America. Experiments in Bolivia and Colombia showed that statistical evaluations can improve the risk assessment. Miller and Rojas (2005) performed the credit scoring of SMEs in Mexico and Colombia, while Milena et al. (2005) studied MFIs in Nicaragua.

Parametric and non-parametric models applied in the development of statistical and non-statistical methods are used in credit scoring models. Among the credit scoring models are: discriminant analysis, linear probability models, probit, logit, linear programming, and neural networks (Kim, 2005). The credit scoring does not replace the traditional process of credit that includes the credit advisors’ knowledge about the customer (Schreiner, 2000). The credit advisors’ role is essential in microfinance because they verify the applicants’ conditions and understands their business operations. This allows the credit advisor to qualitatively judge the microentrepreneurs’ ability to pay (Escalona, 2011). Some of the criticisms about the credit assessment as a whole are that credit scoring is difficult to develop due to the scarce literature. It is noted that a comprehensive loan record database is needed in order to analyze the payers’ behavior; however, MFIs do not register information of the loans applications that were rejected and didn’t pass the analyst’s standard assessment. Hence, there is only information of approved applications (Escalona, 2011). The lack of information becomes a problem when developing systems for measuring microcredit risk. It is also noted that the credit advisor’s decision somehow includes subjectivity.

The prediction of microfinance risks should be approached with different variables or forms to overcome the database limitations (Rayo, Lara & Camino, 2010). Particularly, the gender variable is not widely used in the credit check process. At the financial level, MFI consider women as a more reliable group in comparison with their male peers because they are more responsible and sensitive to social reputation, they have less delinquency and bankruptcy rates, a greater balance of investment, saving capacity, and suggest self-employment projects with better risks (Cortes, 2008). However, women are the weakest sector in impoverished societies. They don’t have financial autonomy or decision-making capacity in regard to the family income. Hence, this turns into a process of financial exclusion and mistrust by the MFIs (Cortes, 2008). This is why it is important to include variables with a cross-sectional gender analysis to discern the good payers from the bad payers.

Although several credit scoring techniques have been studied to improve the credit assessment process in microfinance, no study has considered women microentrepreneurs and their special characteristics. In this scenario, it is essential to research the general knowledge of female good and bad payers’ life expectations, their business management skills, funding management, and each one of the variables included in these concepts. These elements could be included in one of the credit check process phases in order to understand the most relevant and differentiating characteristics of good and bad payers in a survey. This will be useful as filters or variables in a risk rating.

Table 1

Profile of the Informants: Good Payers

Case |

Place of birth |

Age |

Education level |

Marital status |

No. of children |

Business location |

Line of business |

Years of operation |

SBS rating |

1 |

Lima |

41 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

4 |

Villa María del Triunfo |

Restaurant |

8 years |

Normal |

2 |

Pasco |

50 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

3 |

Comas |

Tailoring |

5 years |

Normal |

3 |

Abancay |

39 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

2 |

Santa Anita |

Tailoring and sale of clothing |

10 years |

Normal |

4 |

Pasco |

38 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

2 |

Comas |

Sale of tubers |

12 years |

Normal |

5 |

Lima |

37 |

Higher education |

Single |

1 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Tailoring |

4 years |

Normal |

6 |

Lima |

49 |

Secondary |

Married |

2 |

Comas |

Tailoring |

15 years |

Normal |

7 |

Cusco |

47 |

Higher education |

Married |

3 |

Comas |

Sale of spices |

25 years |

Normal |

8 |

Junín |

57 |

Secondary |

Widow |

2 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Sale of clothing, accessories and purses |

20 years |

Normal |

9 |

Lima |

50 |

Secondary |

Single |

2 |

Los Olivos |

Sale of fruit juices |

4 years |

Normal |

10 |

Lima |

46 |

Secondary |

Married |

4 |

Carabayllo |

Sale of clothes |

12 years |

Normal |

11 |

Lima |

40 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

5 |

Chorrillos |

Sale of groceries |

15 years |

Normal |

12 |

Lima |

47 |

Secondary |

Married |

3 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Sale of videos |

8 years |

Normal |

13 |

Lima |

44 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

4 |

Comas |

Sale of chickens |

14 years |

Normal |

14 |

Junín |

41 |

Higher education |

Married |

4 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Sale of groceries |

15 years |

Normal |

-----

Table 2

Profile of the Informants: Bad Payers

Case |

Place of birth |

Age |

Education level |

Marital status |

No. of children |

Business location |

Line of business |

Years of operation |

SBS rating |

1 |

Lima |

48 |

Secondary |

Married |

4 |

San Martin de Porres |

Sale of clothes |

7 years |

Loss / Doubtful |

2 |

Lima |

44 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

2 |

Villa María del Triunfo |

Tailor |

19 years |

Loss |

3 |

La Libertad |

55 |

Secondary |

Separated |

4 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Lunch menu for children |

5 years |

Loss |

4 |

Lima |

27 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

2 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Sale of groceries in a market |

4 years |

Normal / Poor |

5 |

Lima |

44 |

Secondary |

Single |

0 |

Santiago de Surco |

Technical Service and sale of clothes |

10 years |

Loss |

6 |

Áncash |

43 |

Primary |

Married |

4 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Door-to-door sale of (health and beauty) products |

8 years |

Loss |

7 |

Callao |

34 |

Secondary |

Separated |

3 |

Villa María del Triunfo |

Sale of clothes |

4 years |

Normal / Poor |

8 |

Lima |

65 |

Secondary |

Separated |

3 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Printing business |

3 years |

Loss |

9 |

Lima |

35 |

Secondary |

Married |

2 |

Villa María del Triunfo |

Grocery store |

5 years |

Normal / Doubtful |

10 |

Ica |

32 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

2 |

San Juan de Lurigancho |

Tailor services |

1 year |

Loss |

11 |

Lima |

36 |

Secondary |

Co-habitant |

2 |

Villa María del Triunfo |

Sale of beauty products |

1 year |

Doubtful / Poor |

12 |

Lambayeque |

34 |

Secondary |

Separated |

1 |

Independencia |

Sale of sportswear |

3 years |

Loss |

13 |

Lima |

36 |

Secondary |

Separated |

2 |

Villa María del Triunfo |

Sale of clothes, office supplies, minibus rental |

5 years |

Doubtful / Poor |

Good and bad payers were analyzed taking into account three major activities: life expectations, business management, and funding management. The life expectations aspects were: personal life, family life, finances, quality of life, academic level, business, motivations to be entrepreneurs, factors that motivated them to improve their lives, actions to make their dreams come true, and concerns. The business management aspects were: motivations for starting up their own businesses, business management, important aspects for the business development, formalization, studies, training and update, role of the family in the business, and the relation between the business and their quality of life. The funding management aspects were: connotation of the loan, knowledge and perception of the institution that gave the loan, perception of MFIs, considerations to get their first loan, motivations to pay on time, reasons for non-compliance, financial institutions’ commercial and debt collection strategies. The analysis has allowed identifying and comparing women microentrepreneurs’ behavior within the financial system, and finding the similarities and differences between good and bad payers.

One similarity of good and bad payers in regard to life expectations is that the majority of women microentrepreneurs have not completed higher education. In addition, the factors that motivated them to become entrepreneurs were economic and family problems. Women engaged in the development of a microenterprise are a strong source of income for the households. This involves greater responsibilities, even more so if they are the head of the households. The dreams of both groups are related to the family well-being—especially their children’s—and they want amenities that go beyond the basic needs. Similarly, women entrepreneurs are looking to buy goods for their businesses and are worried about staying healthy to continue working.

Some of the differences were: good payers are the heads of the household, while bad payers make the decisions with their partners or their partners make the decisions. In addition, good payers are fighters, proactive and progressive women, while bad payers are conformists and followers. Good payers are focused on improving their businesses and bad payers prioritize their businesses and focus on their personal well-being. Since women microentrepreneurs take the economic responsibility in their families, they run their businesses with utmost care. This is also related to having a good credit record in the banks, since it is a way to develop their businesses and support their families.

The majority of good payers related their quality of life with having good health to continue working. Bad payers didn’t consider this. Despite the fact that both groups believed that studying and training is important, good payers considered education to improve their businesses, while bad payers related it to areas unrelated to their businesses. For good payers, economic independence is a motivation. This is not the case for bad payers because their motivations are their financial needs. Good payers take actions to make their businesses grow and poor payers limit themselves to only maintain them. Finally, good payers are organized; they save and look for other sources of income. In contrast, bad payers are limited to do only the necessary to maintain their businesses (Table 3).

Table 3

Characteristics related to their life expectations

Components |

Good Payers |

Bad Payers |

|

Family aspects |

Family welfare focused on children to meet their needs, such as: food, clothes, enjoyment, and education (14). |

Family welfare focused on material comforts, such as: housing and furniture (10). |

|

Professional education for their children in order to prevent them from self-sacrificing work, according to their opinion (11). |

Provide professional/technical education to their children so that they can have more opportunities (12). |

||

Personal fulfillment through their children. They feel that their own goals are achieved if their children succeed (10). |

----- |

||

They consider themselves as the heads of the household. This relates to their role in their businesses (12). |

They are the heads of household because they are separated from their partners or are widows (5). |

||

Women entrepreneurs who contribute more to the household economy are the ones that have a higher turnover (11). |

Household decisions are made together (4). |

||

Women who make the decisions are responsible for distributing the household income (9). |

Women microentrepreneurs make the household decisions. In this group we have widows, separated, and unmarried women (6). |

||

Personal aspects |

Improve their businesses (14). |

Improve their businesses (8). |

|

Secure a good old age for the future (3). |

----- |

||

---- |

Personal development is not related to their businesses (5) |

||

---- |

Family welfare focused on material comforts for them and their families (7). |

||

Economic aspects |

Buy goods for their businesses: their own property, transportation, equipment, and shelves (11). |

Buy goods for their businesses: their own property, transportation, equipment, and shelves (7). |

|

They want to have their own houses or to finish building the ones that they already have (4). |

They want to have their own houses or to finish building the ones that they already have (7). |

||

---- |

Goods for personal enjoyment and transportation (3). |

||

Quality of life aspects |

Take care of their health because they believe that getting sick is expensive and they don’t have health insurance (11). |

Take care of their health to continue working (4). |

|

Secure a good old age in order to not be dependent on their children (3). |

Secure their family members’ future (7). |

||

They want additional amenities and use the business assets for family enjoyment too (6). |

They want additional amenities that allow them to feel in a better social position (5). |

||

Academic aspects |

In the future, they need and wish to study in order to improve their businesses. They want to study management, go to culinary school and design new dishes (5). |

They have studied subjects related to their businesses and other areas (3). |

|

They said it is necessary, but they didn’t say what or when they would pursue studies (9). |

They said it is necessary, but they didn’t say what or when they would pursue studies (2). |

||

---- |

They said it is not necessary to study to run their businesses (6). |

||

Business aspects |

Have assets for their businesses in order to own a property (12). |

Have assets for their businesses in order to own a property (4). |

|

Always have a business to ensure a permanent income (4). |

They want to maintain a stable business, make it grow if they can, and maintain the current income without making a greater effort. (5) |

||

They don't want debts in order to save and self-fund (3). |

---- |

||

Motivations to continue being an entrepreneur |

They want their children to look up to their spirit of achievement. They want to see their children’s success (14). |

They want their children to complete their undergraduate degrees and their younger children to have the opportunity to study (9). |

|

They want financial independence. They don't want to depend on their partner’s income for their personal, family or business expenses and, in some cases, they are the heads of the household (7). |

They want financial independence to enjoy, travel, and buy personal items (2). |

||

They want to grow. Since they were abandoned, they try to demonstrate self-sufficiency, to feel good, to take this opportunity and support. (4). |

They want to grow through their businesses in order to prove that they could do something for themselves. (4). |

||

---- |

They want to improve their current economic situation, because several of them are single mothers who are the only financial support of the household (9). |

||

Factors that motivated them to improve their lives |

They don't want their children to experience the economic deprivation they suffered during childhood and adolescence (5). |

They don't want their children to experience the economic deprivation they suffered during childhood and adolescence (8). |

|

Their family problems made them to look for an alternative to generate resources (7). |

Their family problems made them to look for an alternative to generate resources (5). |

||

They had the example of working parents. They want to continue working like their parents (6). |

They had the example of working parents. They want to continue working like their parents (5). |

||

Personality aspects |

They are fighters, business or personal difficulties don’t daunt them (11). |

---- |

|

They are proactive, they take the initiative to generate new income (9) |

They are proactive, they take the initiative to generate new income (3) |

||

They are progressive, they strive to work in order to continue growing economically (5). |

They are conformists, they don’t aim to grow, only to cover their expenses (4). |

||

---- |

They are followers, they leave the family decision to their partners and show dependence to their ex-partners (8). |

||

Actions taken to achieve their dreams |

They organize their activities and arrange their time to take on the roles of microentrepreneurs and mother (4). |

---- |

|

They look for other sources of income and develop side businesses: transportation, lenders, and rentals (4). |

---- |

||

They want self-financing. They save in order not to depend on third parties (6). |

---- |

||

They do not mention the subject. |

They keep doing the same thing. They think that what they do is enough to get want they want (9). |

||

They do not mention the subject. |

They set their goals, they only mention them generically without giving clear examples (2). |

||

Life concerns |

Staying healthy. They think that without health they can’t continue working (10). |

Staying healthy. They think that without health they can’t continue working (10). |

|

Family concerns. They want their children to make the most of their time and to meet the family needs (5). |

---- |

||

They want to pay their debts. They emphasize to be up to date with their payments in order to maintain a good credit record and be eligible to get other loans (14). |

They want to get loans. They think that loans are a source of capital for their businesses, but they can’t get one due to default (4). |

||

Secure a good old age. They want to secure their future with businesses that provide income and make the most of their time while they can still work (3). |

---- |

||

Necessity-motivated entrepreneurship occurred in both good and bad payers. They have their families’ support for business, especially their children’s support; however, they don’t want to work with family members to avoid problems. The business has enabled them to educate their children. They have experience from their previous jobs or with family. They think that, for business development, experience is more important than training. They also consider that customer-friendliness is a more differentiating element than the business location. Finally, both groups have little information about formalization and have informal businesses.

One of the differences was that good payers register their income and expenses in an organized way and they know their profits in detail, while bad payers do not have a register of their income and expenses. They only calculate their earnings intuitively. Despite of the financial illiteracy in this sector, good payers have achieved to empirically manage their businesses out of necessity, whereas this activity is a secondary aspect for bad payers. Hence, good payers’ businesses might have a better growth and might make payments easily because they distribute the money accurately.

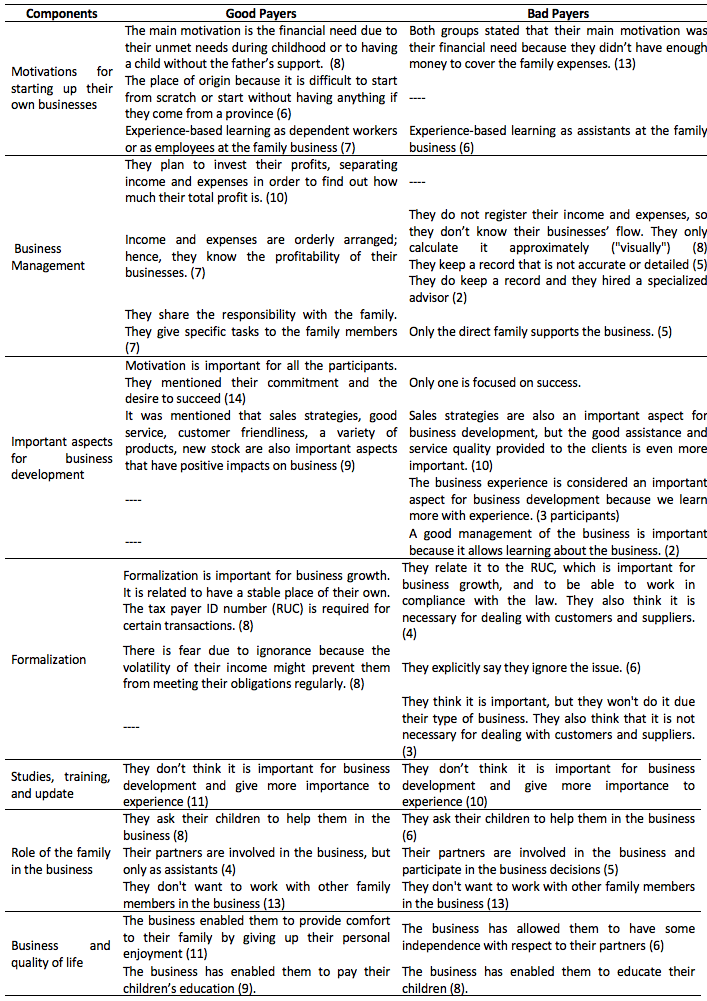

Good payers are interested in the growth of their business, while poor payers aren’t. For business development, good payers are goal-oriented while bad payers aren’t. In addition, good payers think that formalization is necessary for growth. Bad payers tend to personally enjoy the business profits, while good payers hardly do that. Good payers think that their businesses allowed them to provide comfort to their families by giving up their personal enjoyment. In contrast, bad payers think that their businesses enabled them to be independent from their partners (Table 4).

Table 4

Characteristics related to business management

Good and bad payers know the different sources of financing for microenterprises. They also think that loans are helpful to the business. Both groups recognize that MFIs are more accessible and they appreciate the personalized service they provide.

Some of the differences are that bad payers are more aware of the financial institutions’ rates, products and processes than the good payers. Good payers think that loans have a positive connotation and responsibility, while bad payers think it is a concern and an additional expense. In addition, good payers are more cautious and analyze the decision to get a credit, while poor payers are more emotional and do not thoroughly analyze these decisions. Apparently, the knowledge of these financial products is not necessarily related to credit valuation or to the responsible use (Table 5).

Table 5

Aspects related to funding

Components |

Good Payers |

Bad Payers |

Meaning of the loan |

Loans help businesses to grow. The only way to start up a business is by getting a loan (9) |

Loans help businesses to grow. The only way to start up a business is by getting a loan (9) |

It is a responsibility. The payment should be made on time in order to apply again and have a better line of credit (8) |

---- |

|

It improves the family welfare. Loans allow covering the family expenses with the business income (3) |

---- |

|

---- |

It is a constant concern, because they have pending payments that they couldn’t make (11) |

|

---- |

It is an additional expense. They are aware of the additional payment for interests (4) |

|

Knowledge and perception of the entities that give loans. |

They identify themselves with MFIs thanks to the direct negotiations. (14) |

They identify themselves with MFIs thanks to the direct negotiations. (10) |

Banks are perceived as distant or inaccessible institutions. (10) |

They think that banks charge lower interest rates than MFIs. (6) |

|

If used together, the profits are saved. (3) |

If used together, it is based on trust among the parties. (5) |

|

They turn to lenders in extreme cases due to the high interest rates. They believe that they have an inadequate method of collection. (2) |

Lenders are not an appropriate form of funding because they could extort them. (6) |

|

Perception of MFIs |

They are the most accessible source. The agencies They have good relationships with the clients and they can easily get the loan. (6) |

These institutions are perceived as accessible. They have good relationships with the clients. (8) |

Good advice is valued because the provided information is clear and precise. (5) |

They appreciate the personalized customized assistance and the provided information. (7) |

|

They are perceived as institutions that charge lower interest rates than banks. (6) |

They charge lower interest rates than banks. (3) |

|

---- |

They charge higher interest rates than banks. (4) |

|

Women microentrepreneurs’ opinions about their first loan |

They had their families’ support to pay the installments. Only in extreme cases, when they can’t cover their expenses, they turn to their older children. (2) |

They consider the family support to pay the loan installments. The incidents with the family relationship have a direct impact on the payments. (3). |

Family involvement in the decision to get a loan. They ask their relatives to support their operations, since they did not have any property of their own to use it as collateral. (4) |

The opinion of the family has been considered to make the decision of getting a loan. (8) |

|

They were afraid of not being able to pay the loans. Initially, they were afraid because they haven’t worked with financial entities before. (11) |

---- |

|

---- |

They said that they don’t reflect on what it would mean to get a loan. (4) |

|

Motivations to pay on time |

Being active in the financial system and recognized as good payers motivates them, and gives them the opportunity to get loans from other institutions. (11) |

Does Not Apply |

Having access to larger loans because they know that a good credit history creates a confident image for these institutions. (4) |

Does Not Apply |

|

Not paying high interest rates. Third parties told them that not paying on time increases the interest rates. (4) |

Does Not Apply |

|

They don’t want to discredit its public image because they know that there are excessive and uneasy collection methods, and they don't want to be exposed to this situation. (2) |

Does Not Apply |

|

Reasons for non-compliance |

Does Not Apply |

Family and personal factors based on their own health or their relatives’ health problems (7) |

Does Not Apply |

External factors related to the business, decrease in sales, competitors’ low prices, and construction sites near the business location that prevented the arrival of customers (5) |

|

Does Not Apply |

Factors related to theft or uncontrolled events that caused them to leave their business or stop working for a period of time. (3) |

|

Financial entities approach to women microentrepreneurs |

Financial institutions reached them to their homes or businesses to offer them their financial products. (11) |

Does Not Apply |

Financial entities contacted them through friends or acquaintances. (3) |

Does Not Apply |

|

The form of contact less valued by women entrepreneurs are telephone calls or flyers. (6) |

Does Not Apply |

|

Strategies to collect the loans |

Does Not Apply |

Legal actions were taken. Some of them even had to seek legal advice in order to keep the properties that were used as collateral (2) |

Does Not Apply |

They experienced awkward situations related to the collection method of MFIs. They say that it is excessive and, in some cases, they don’t respect their rights (6) |

The study results show that even though female borrowers are good payers in general, they are not a homogeneous population. A qualitative exploration of women microentrepreneurs provides a greater approach to the information that contributes to the credit scoring analysis and credit check in general.

The results show that there are similarities between women microentrepreneurs with good and bad payment behavior, such as: (a) the priority in both groups is welfare and children’s self-improvement; (b) factors that motivated them to become entrepreneurs was the economic deprivation they suffered during childhood; (c) experience is more important than training in business development; (d) a good customer service is a differentiator and; (e) loans have a positive impact on their business and they appreciate the accessibility that MFIs provide them as entrepreneurs. The main differences found between the two groups are related to the superlative level of independence, non-conformism, orderliness, and almost exclusive dedication to their business. Good payers make more sacrifices related to their personal life than bad payers.

The study identified variables that allow discerning between women microentrepreneurs with good and bad payment history. These variables are related to their life expectancy, and business and funding management, which favors a better understanding of such population. The obtained results can be used by MFIs as qualitative variables in risk scorings or can be included in the credit advisors’ evaluation sheets at MFIs.

As a result, it is proposed to create an instrument (survey) as part of the credit check process of women entrepreneurs. It shall include questions about the differentiating characteristics found in this research, which are grouped in six factors according to the risk level: (a) “Orderliness” factor, which shows the level of organization with which they maintain the business accounts. They should accurately organize the income, expenses and profits details; (b) “Conformism” factor, which shows the microentrepreneurs level of effort to improve their businesses; (c) “Dedication to the business” factor, which reflects the degree to which all their life aspects are related to their business; (d) “Enjoyment of personal life” factor, which reflects a responsible behavior with regard to their obligations; (f) “Dependence” factor, which shows the level of independence with which they make decisions at home and at their businesses.

The implementation of a survey at the beginning of the credit process and the analysis of the credit performance for several years are proposed in order to analyze the validity of the instrument. In addition, the inclusion of this additional survey in a representative group within the MFIs’ women microentrepreneurs’ portfolio is recommended; in this way, the obtained results can be extrapolated to their future portfolio in this segment.

Figure 1

Considered factors to measure women

entrepreneurs’ level of credit risk

Higher risk |

Level of dependence |

Lower risk |

||||

1. Completely dependent |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5. Not dependent |

||

Level of conformism |

||||||

1. Completely conformist |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5. Not conformist |

||

Level of orderliness |

||||||

1. Completely disorganized |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5. Completely organized |

||

Level of exclusive dedication to the business |

||||||

1. Poor dedication to the business |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5. Completely dedicated to the business |

||

Level of sacrifice related to their personal lives |

||||||

1. Focuses on personal interests |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5. Does not focus on personal interests |

||

Amat, O. (2014). Scoring y rating. Cómo se elaboran e interpretan. Boletín N°2 desupercontable.com . Retrieved from http://www.supercontable.com/envios/articulos/BOLETIN_TU-ASESOR_02_2014_Articulo_5.htm

Banda, H, & Garza, R. (2014). Aplicación teórica del método de Holt-Winters al problema de credit scoring de las instituciones de microfinazas. Mercado y Negocios, 15 (2), 5-21. Retrieved from Https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/5811252.pdf

Bierman, H., & Hausman, W. (1970). The credit garanting decision.Management Science, 519-532.

Cortés, F. (2008). Las microfinanzas: caracterización e instrumentos. Serie Banca Social. Retrieved from Http://www.publicacionescajamar.es/pdf/series-tematicas/banca-social/las-microfinanzas-caracterizacion-2.pdf

D’Espallier, B., Guerín, I. & Mersland, R. (2011). Women and repayment in microfinance: A global analysis. World Development, 39(5), 758-772. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.10.008

Delfiner, M., Pailhé, C., Perón, S. (2006). Microfinanzas: un análisis de experiencias alternativas de regulación. Retrieved from http://www.bcra.gob.ar/Pdfs/Publicaciones/microfinanzas.pdf

Escalona, A. (2011). Uso de los Modelos Credit Scoring en Microfinanzas. Master’s Thesis. Institución de enseñanza e investigación en ciencias agrícolas, Campus Montecillo. Retrieved from http://ri.uaemex.mx/bitstream/handle/20.500.11799/40683/http://colposdigital.colpos.mx:8080/jspui/bitstream/handle/10521/414/Escalona_Cortes_A_MC_Estadistica_2011.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=yTESIS-IMF_Password_Removed.pdf?sequence=1

Fisher, R (1936). The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Annals of Eugenucs, 179-188. Retrieved from Http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-1809.1936.tb02137.x/epdf

García, F. & Díaz, Y. (2011, April). Los microcréditos como herramienta de desarrollo: Revisión teórica y propuesta piloto para el África Subsahariana. CIRIEC- España, Revista Económica Pública y Social y Cooperativa, 70, 101-126. Retrieved from: http://www.ciriec-revistaeconomia.es/banco/7005_Garcia_y_Diaz.pdf

Gibbons, D. S. & Kasim, S. (1990). Banking on the rural poor in Peninsular Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: AIM.

Gutiérrez, J. (2009). Microfinanzas y desarrollo: situación actual, debates y perspectivas. Hegoa working papers No. 49. Retrieved from Https://eii.uva.es/webcooperacion/doc/formacion/gutierrez-2009-las-microfinanzas-situacic3b3n-actual-debates-y-perspectivas.pdf

Gutiérrez, M. (2007). Modelos de Credit Scoring-Qué, cómo, cuándo y para qué. Retrieved from http://www2.bcra.gob.ar/Pdfs/Publicaciones/CreditScoring.pdf

Hand, D.., & Henley, W. (1997). Statical classification methods in consumer credit scoring: A review. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 523-541. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-985X.1997.00078.x/epdf

Heller, L. (2010). Women entrepreneurs in Latin America and the Caribbean. Reality, obstacles, and challenges. Division for Gender Affairs (ECLAC), Series 93. Retrieved from http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/4/38314/Serie93.pdf

Hossain, M. (1988). Credit for alleviation of rural poverty: The Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. Retrieved from Http://ageconsearch.tind.io//bitstream/42590/2/rr65.pdf

http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/4/38314/Serie93.pdf

Hulme, D. (1991). Field reports. The Malawi Mundi fund: Daughter of Grameen. Journal of International Development, 3(3), 427-431. Retrieved from Http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jid.4010030315/pdf

Kelley, D., Singer, S., & Herrington, M. (2016). GEM 2015/16 Global Report. Retrieved from: http://www.gemconsortium.org/report/49480

Kevane, M., & Wydick, B. (2001). Microenterprise lending to female entrepreneurs: Sacrificing economic growth for poverty alleviation? World Development, 29(7), 1225-1236. Retrieved from Http://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=econ

Kim, J. (2005). A credit risk model for agricultural loan portfolios under the new based capital accord. Dissertation submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University.

Krueger, R. & Casey, M. (2000). Focus group: A practical guide for applied research. (3rd ed.). California, CA: Sage.

McCarter, E. (2006). Women and microfinance: Why we should do more. University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class 6(2), 353-366. Retrieved from http://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/margin6&div=23&id=&page=

Microfinance Information Exchange. (2009, December). The MicroBanking Bulletin (Issue 19). Retrieved from https://www.themix.org/sites/default/files/publications/MBB%2019%20-%20December%202009_0.pdf

Milena, E., Miller, M Y Simbaquebba, L. (2005). The case for information sharing by microfinace institutions: empirical evidence of the value of credit bureau-type date in the Nicaraguan microfinance sector. New York, NY: The Wold Bank, mimeo.

Miller, M., & Rojas, D. (2005). Improving acces to credit for smes: an empirical analysis of the viability of pooled data SME credit scoring model in Brazil, Colombia & Mexico. New York: the World Bank.

Ministry of Labor and Employment Promotion (MINTRA) (2009).Mujer en el mercado laboral peruano: 2009. Retrieved from Http://www.mintra.gob.pe/archivos/file/informes/informe_anual_mujer_mercado_laboral.pdf

Myers, J., & Forgy, E. (1936). Development of numerical credit evaluation systems. Journal of American Statistical Association, 58, 799-806. Retrieved from http://socsci2.ucsd.edu/~aronatas/project/academic/Comparison%20of%20Discriminant%20and%20Regression%20analysis%20for%20cred.pdf

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2015). La mujer en la gestión empresarial: cobrando impulso. World Report. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_334882.pdf

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2016). Panorama laboral 2016. Latin America and the Caribbean. Lima: Author. Retrieved from Http://ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_537803.pdf

Orgel, Y. (1970). A credit scoring model for commercial loans. Journal of Money, 2 (4), 435-445. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1991095.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A710ce31c988484b750552bdd9105af66

Pedroza, P. (2011, octubre). Microfinanzas en América Latina y El Caribe: El sector en cifras 2011. Washington, DC: Multilateral Investment Fund (IDB) Retrieved from https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/5375/Microfinanzas%20en%20Am%C3%A9rica%20Latina%20y%20el%20Caribe:%20El%20sector%20en%20cifras%202011.pdf?sequence=1

Portocarrero, F., Trivelli, C. & Alvarado, J. (2002). Microcrédito en el Perú: Quiénes piden, quiénes dan. Lima, Peru: Economic and Social Research Consortium (CIES).

Powers, J. & Magnoni, B. (2010, April). Dueña de tu propia empresa: Identificación, análisis y superación de las limitaciones a las pequeñas empresas de las mujeres en América Latina y El Caribe. Washington, DC: Multilateral Investment Fund (IDB) Retrieved from https://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/6257?locale-attribute=es&scope=123456789/11&thumbnail=false&order=desc&rpp=5&sort_by=score&page=1&query=salud+de+la+mujer+indigena&group_by=none&etal=0&filtertype_0=subject_en&filter_0=Microbusinesses+%2526+Microfinance&filter_relational_operator_0=equals

Programme Promoting Gender Equality [GTZ], World Bank, & Inter-American Development Bank [IDB]. (2010). Mujeres empresarias: barreras y oportunidades en el sector privado formal en América Latina y El Caribe. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLACREGTOPPOVANA/Resources/840442-1260809819258/Libro_Mujeres_Empresarias.pdf

Rayo, S., Lara, J. & Camino, D. (2010). Un modelo de credit scoring para instituciones de microfinanzas en el marco de Basilea II. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 15(28), 89-124. Retrieved from Http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/jefas/v15n28/a05v15n28.pdf

Schreiner, M. (2000). La clasificación en las Microfinanzas: ¿Podrá funcionar? Microfinance Risk: Managment and Center for Social Development. Retrieved from http://www.microfinance.com/Castellano/Documentos/Scoring_Podra_Funcionar.pdf

Serida, J., Alzamora, J., Guerrero, C., Borda, A., & Morales, O. (2016). Global entrepreneurship Monitor: Peru 2015-2016. Lima: ESAN University. Retrieved from http://www.esan.edu.pe/publicaciones/2016/12/15/reporte_GEM%202015-2016%20final.pdf

Stewart, D., Shamdasani, P., & Rook, D. (2007). Focus groups: Theory and practice (2nd ed.). London, England: Thousand Oaks.

Torre, B., Sainz,I., Sanfilippo, S., & López, C. (2012). Guía sobre microcréditos. Cantabria, Spain: University of Cantabria Retrieved from http://www.ocud.es/files/doc851/guiamicrocreditosmail.pdf

Veeramani, P., Selvaraju, D., & Ajithkumar, D. (2009). Women enpowerment through microentrepreneurship. A sociological Review. Indigenous Practices in Entrepreneurship, 5(2), 83-96. Retrieved from: http://www.asiaentrepreneurshipjournal.com/2009/AJES_se_V_(2)_2009.pdf.

Viganó, L. (1993). A credit-scoring model for development banks: An African case study. Saving and Development, 4, 441-482. Retrieved from http://www00.unibg.it/dati/persone/710/1202-1993.pdf

1. CENTRUM Católica Graduate Business School, Lima, Perú Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, Perú. Email: bavolio@pucp.pe

2. Email: accostupa.rosalyn@gmail.com

3. Email: ronar.bermudez@gmail.com

4. Email: roma0381@gmail.com

5. Email: Ronald.francisco.montes.chavez@gmail.com

6. The TEA is published by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, which is the world's most recognized indicator of entrepreneurial activity. The indicator measures the individuals at two stages of the entrepreneurship process: nascent entrepreneurs and new business owners (Kelley, Brush, Greene, Herrinfton, Ali & Kew, 2015, p. 17).