Vol. 39 (Number 50) Year 2018. Page 12

PONOMAREV, Oleg B. 1; SVETUNKOV, Sergey G. 2

Received: 26/06/2018 • Approved: 05/09/2018 • Published 15/12/2018

ABSTRACT: The theory of entrepreneurship is one of the developed sections of the modern economy. However, some of the provisions of this theory are in contradiction with each other or require clarification. These are some of the properties of the entrepreneur, which distin-guish economists, sociologists and psychologists. For example, risk appetite in the economy is considered an indispensable property of the entrepreneur, and sociologists have revealed that not every entrepreneur is ready to resort to taking a risky decision. In order to remove these contradictions in the article it is proposed to treat the entrepreneur not as a static phenomenon, but as a dynamic phenomenon. The factor of dynamics that influences the nature and properties of the entrepreneur is to consider entrepreneurial in-come. This entrepreneurial dynamics is proposed to describe with the help of a graphic model of the entrepreneur's life cycle. The entrepreneur's life-cycle model considers the dependence of the individual freedom and independence of the entrepreneur, which he receives with the growth of entrepreneurial income. In these life cycle consistently exam-ines the dynamics of the entrepreneur from the stage of small and small business to the stage of the capitalist. At the last stage, when an entrepreneur becomes a capitalist, he faces a choice of the further path of development. This point on the graphic model of the life cycle of the entrepreneur is called a bifurcation point, and we have named the options of choice as attractors. |

RESUMEN: La teoría del emprendimiento es uno de los factores mas desarrollados de la economía moderna. Sin embargo, algunas de las disposiciones de esta teoría están en contradicción entre sí o requieren una aclaración. Estas son algunas de las propiedades del empresario, que distinguen a economistas, sociólogos y psicólogos. Por ejemplo, el apetito por el riesgo en la economía se considera una propiedad indispensable del empresario, y los sociólogos han revelado que no todos los empresarios están listos para recurrir a tomar una decisión arriesgada. Para eliminar estas contradicciones en el artículo, se propone tratar al empresario no como un fenómeno estático, sino como un fenómeno dinámico. El factor de dinámica que influye en la naturaleza y las propiedades del empresario es considerar el ingreso empresarial. Se propone describir esta dinámica empresarial con la ayuda de un modelo gráfico del ciclo de vida del empresario. El modelo de ciclo de vida del empresario considera la dependencia de la libertad individual y la independencia del empresario, que recibe con el crecimiento del ingreso empresarial. En este ciclo de vida, se examinan de forma coherente la dinámica del empresario desde la etapa de la pequeña y pequeña empresa hasta la etapa del capitalista. En la última etapa, cuando un empresario se convierte en capitalista, se enfrenta a la elección de un camino más hacia el desarrollo. Este punto en el modelo gráfico del ciclo de vida del empresario se denomina punto de bifurcación, y hemos nombrado las opciones de elección como atractores. Palabras clave: emprendimiento, enfoque dinámico, ciclo de vida de un emprendedor, modelo gráfico, capital, libertad personal. |

With a history spanning several centuries, entrepreneurship theory is one of the most prominent areas in economics. As civilization develops entrepreneurship changes. New forms and new attributes reveal themselves to researchers. Responding to these changes, entrepreneurship theory develops and expands. Today, entrepreneurship theory is paying increasing attention to research on the phenomenon of socially responsible business. Although first studies in the field date back thirty years ago, relevant findings are often presented in an erratic and non-systematic manner. Sometimes, these findings do not cohere with the dogmatic principles of entrepreneurship theory. Moreover, the theory does not explain either this or any other paradoxes.

A thorough analysis of entrepreneurship theory and its applications suggests that the underlying principles are eclectic and non-systematic. The properties of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship identified by researchers do not cohere when juxtaposed within a comparative analysis. Sometimes these properties are in conflict with each other. Moreover, the basic concepts of the theory – entrepreneur, entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial ability, etc. – have no clear definition and their existing interpretations often contradict each other.

There is much discussion about a desirable form of governance or, at least, a preferable entrepreneurial policy. The two extremes are liberalism and bureaucratism. The former grants entrepreneurs almost complete freedom and it suggests that competition is the best economic regulator. Thus, any government intervention into business regulation is inadmissible. The latter doctrine holds that entrepreneurship is irrational and spontaneous and that it inevitably leads to repeated economic crises. Therefore, entrepreneurship should be subject to governmental control.

Most researchers of this important economic phenomenon view the entrepreneur as a steady and unvarying unit of analysis. Identifying stable connections in business dynamics, studying the changing characteristics of this dynamics, and detecting the patterns of entrepreneurial activities will contribute to a systematic presentation of the key findings that have been obtained so far. An important role may be played by an analysis of development trends in entrepreneurship from its very emergence at the dawn of civilization to the present day. All the above constitutes the historical method. However, such a dynamic approach can be applied to identifying not only external factors affecting entrepreneurship but also the changes in entrepreneurship throughout the rather short life cycle of an entrepreneur.

Trade has been a major form of entrepreneurship for thousands of years. Thus, in the very beginning, researchers studied the phenomenon of entrepreneurship from the perspective of trade. It is no coincidence that the first economic methodology was mercantilism – a doctrine of national wealth supported by international trade. Richard Cantillon – who introduced the term ‘entrepreneur’ to economic science – was a mercantilist. His Essays on the Nature of Commerce in General are remarkable not only for addressing the entrepreneur as an agent of the economy for the very first time but also for identifying the distinguishing characteristics of this agent. According to Cantillon, entrepreneurs take all the risk in different economic transactions – they buy at a certain price to sell at an uncertain one. The difference between supply and demand provides an opportunity for entrepreneurs to buy cheaply and sell dear. According to Cantallion, regardless of whether an entrepreneur is a trader, a landowner, or even a capitalist exploiting the labor of others, the role of entrepreneur is performed by the person who makes decisions under uncertainty. Cantillon believed that entrepreneurship was essentially foresight and willingness to embrace risk. An entrepreneur’s income is remuneration for taking risk. In Europe of the time, all entrepreneurs worked under risk – some of them prospered and others went bankrupt (Cantillon, 2009, p.18).

Considered an axiom, Cantillon’s argument that a propensity for decision-making under risk is inherent in an entrepreneur was not challenged for a long time. Many economists still add this inherent propensity to the list of attributes of a typical entrepreneur. Cantillon’s argument has attracted interest from psychologists who carried out a series of studies into entrepreneurs’ attitudes to risk. Notable results were obtained by Robert Brockhaus. His findings were published in the chapter “The psychology of the entrepreneur” in Encyclopaedia of entrepreneurship (Brockhaus, 1982). In Brockhaus’s experiment, test participants were presented with a number of choices between less risk-fraught but less attractive and more risk-fraught and more attractive alternatives. Brockhaus distinguished the following components of risk:

The participants were entrepreneurs and managers of different levels. Based on his findings, Brockhaus argued that successful entrepreneurs were moderate risk-takers. No difference between the managers’ and the entrepreneurs’ attitudes to risk was found. Brockhaus empirically disproved Cantillon’s thesis about risk-taking propensity in entrepreneurs. Some – but not all – entrepreneurs have propensity for risk-taking and this propensity should be taken off the list of the distinguishing characteristics of entrepreneurs.

Based on Brockhaus’s and his own findings, Karl-Erik Wärneryd concluded that there was a link between self-esteem and risk-taking. The higher self-esteem, the more probable it is that the entrepreneur will take part in a high-risk transaction, and vice versa (Wärneryd, 1999,p. 243). Thus, propensity for risk-taking is an attribute of a certain psychological makeup rather than of the psychological makeup of the entrepreneur.

However, some researchers continue to argue that each entrepreneur has propensity for decision-making under risk (Mullins, J. and D. Forlani; Chell; Cunningham J.A. and O'Kane C.).

Jean-Baptiste Say did not distinguish the entrepreneur at all. Say was prone to broader generalizations: “it commonly happens, that one man studies the laws and conduct of nature; that is to say, the philosopher, or man of science, of whose knowledge another avails himself to create useful products, being either agriculturist, manufacturer, or trader; while the third supplies the executive exertion, under the direction of the former two; which third person is the operative workman or labourer” (Say, 2008). Philosophers (or researchers, should modern terminology be used) study the laws of nature. Manufacturers and entrepreneurs (Say did not distinguish between the two categories) employ this knowledge to organize production. The product requires the labor of workers. In Chapter VI “Of Operations Alike Common to All Branches of Industry” of his work A Treatise on Political Economy”, Say argued that the manufacturer (entrepreneur) had special knowledge and skills. The economist wrote: “I have said that the cultivator, the manufacturer, the trader, make it their business to turn to profit the knowledge already acquired, and apply it to the satisfaction of human wants. I ought further to add, that they have need of knowledge of another kind, which can only be gained in the practical pursuit of their respective occupations, and may be called their technical skill” (Say, 2008). The entrepreneur employs knowledge in pursuit of best economic practices and of desired goals.

As early as the mid-20th century, economists revealed that economic decisions were made under risk and uncertainty. George S. Odiorne argued that a rational economic activity is impossible since “Organizations have a tendency to disperse… purposiveness… Managers and bosses in organizations lose sight of subordinate goals” (George S. Odiorne, p.60).

In the early 18th century, François Quesnay stressed that free competition between industries and free movement of capitals between them resulted in that the rate of return on capital tended to the average across industries and trade and that supply met the demand (Quesnay, 2016). Thus, the entrepreneur is a guarantor of an economy’s harmonious development. However, in the 20th century, economic science increasingly viewed the entrepreneur as a shatterer of economic peace. This was emphasised in the early 20th century by Thorstein Veblen (Veblen, 2014). In his Essays in Our Changing Order, Veblen argued that the entrepreneur’s pursuit of maximum profits translated into the destruction of economic harmony. According to Veblen, greed for fast profits was behind overproduction crises. This idea was developed further by Joseph A. Schumpeter (Schumpeter, 2013) in his description of the entrepreneurs’ propensity to secure monopolistic profits through innovations. As Israel M. Kirzner argued, entrepreneurship was aimed to destabilize markets, since instability was a source of maximum profits. Destabilization can result from the creation of new products or it can be caused otherwise. Thus, the entrepreneurial function is interpreted more broadly than the innovative one. Innovations constitute one of the many entrepreneurial functions and this function is not even a dominant one. Moreover, entrepreneurs do not pursue instability – it is a mere side effect of their efforts. The entrepreneur’s propensity for gaining profits is key, whereas innovations and market instability are a mere consequence (Kirzner, 1978).

The above does not exhaust the list of contradictions and inconsistencies plaguing economic science when it comes to the perceptions of the phenomenon of the entrepreneur. Petra Gibcus and Elissaveta Ivanova carried out a thorough analysis of works spanning from the 20th to the 21st centuries (Ivanova and Gibcus 2003). The researchers listed some of these contradictions. Thus, it suffices to say that entrepreneurship theory has not yet become a systematic and consistent part of economic science.

A crucial and constructive analysis of the principles of entrepreneurship theory, which has been developed over centuries, paired with an analysis of ample empirical data on contemporary businesses show that many of such principles contradict each other or stand for conflicting properties. This paradox will be considered below.

We believe that the dynamic approach to the complex phenomenon of the entrepreneur is key. Ichak Adizes made the first move in this direction in his book Managing Corporate Lifecycles (Adizes, 2004). Adizes argued that the lifecycle of an entrepreneur strongly affected the efficiency of entrepreneurship and the probability of embarking on that path. As the firm matures, the entrepreneur’s human and social capital grows. A wide network of contacts and information resources is used by the entrepreneur to gain tacit knowledge, including that on informal rules of conduct – following those rules contributes to success and ignoring them leads to a failure. Adizes stressed that the older a firm grew the less life energy it had. In that case, routine was increasingly preferred over innovations. Alternative economic opportunities have a negative effect on the propensity to revive the entrepreneurial element of the firm. Azides emphasised that the properties of an entrepreneur changed over time. However, he did not elaborate on the nature or rate of such changes.

Theory of economics and entrepreneurship did not fully embrace the fact that had been stated by Alfred Marshall at the beginning of the 20th century. Marshall stressed that children of entrepreneurs did not usually follow in the footsteps of their parents – the new generation chose to preserve existing businesses rather than to engage in entrepreneurship.

Several decades later, a similar idea was voiced by Joseph Schumpeter (Schumpeter, 2013). Schumpeter wrote that children of successful entrepreneurs joined the class of capitalists without bothering themselves with exploring new areas or expanding their businesses. The new generation merely kept up the level attained by the founders of the business dynasty.

It is not rare that a child of a musician becomes a musician. For instance, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was the son of the musician Leopold Mozart. Children of physicists become physicists. Sergey Kapitsa – a specialist in Earth magnetism, applied electrodynamics, and particle physics – was the son of Pyotr Kapitsa, the Nobel laureate in physics. Similarly, children of capitalists become capitalists (the Rockefeller family), children of farmers farmers, children of workers workers, and children of sotrekeepers storekeepers.

There are few stories of children of entrepreneurs becoming entrepreneurs. One of them is that of Donald Trump, although it is difficult to call him an entrepreneur proper. His father was a true entrepreneur who started from scratch, whereas Donald Trump himself was the son of a capitalist and built on the family fortune. He did not start from scratch, as most entrepreneurs do, but from a million dollars. Donald Trump began his career not in his own company but in that of his father. A business success, Trump exceeded his father’s achievements. However, this is still a story of a capitalist. There are other capitalist families in which children were more successful than their parents who had earned the seed capital – the Rockefellers, the Rothschilds, and others.

Therefore, entrepreneurship is not just conducting independent business at one’s own risk and discretion. Entrepreneurship is business in dynamic terms – it pursues a common goal that makes a businessperson an entrepreneur.

We surveyed over 450 successful Russian entrepreneurs. One of the questions concerned the respondents’ motivation to become entrepreneurs. The answers were as follows:

All the above variants are interconnected. A wealthy person can afford all the social goods that are unavailable to people without capital – personal security, family protection, healthcare, etc. Accumulating personal wealth becomes a way towards independence and freedom that remain unattainable for those without substantial fortunes.

The motive of “making one’s way in life” can also be interpreted as a desire for freedom and independence, since it means a rapid ascent up the ladder of vertical social mobility. Current statistics reveal that, among 100 richest people in the world, only 27 inherited their wealth. The other 73 are rich by their own efforts – they have ‘made their way in life’. Out of the 72 people, 18 do not have a higher education and 36 (a half!) were born in poverty.

Thus, a desire for freedom and independence is a major distinguishing characteristic of an entrepreneur. This basic motive makes a person embark on the exciting and dangerous journey of entrepreneurship.

Therefore, entrepreneurs are businesspersons who strive to enhance personal freedom through increasing their capital at their own risk and discretion. Definitions that do not cover the idea of dynamism or the basic motive are not accurate.

Such an interpretation elucidates the fact that was emphasised by Marshall and Schumpeter – the descendants of successful entrepreneurs do not become entrepreneurs. Born in wealth, they enjoy personal freedom and independence sustained by the capital accumulated by the founder of the business dynasty. Children of wealthy entrepreneurs are not motivated to work hard to increase their capital – this will not grant them any new freedoms. Members of the highest social strata, they have everything. For them, there is little sense in achieving greater success. Of course, younger generations can become richer but they will do it building on the existing capital rather than working round the clock to develop their emerging business as all the entrepreneurs do.

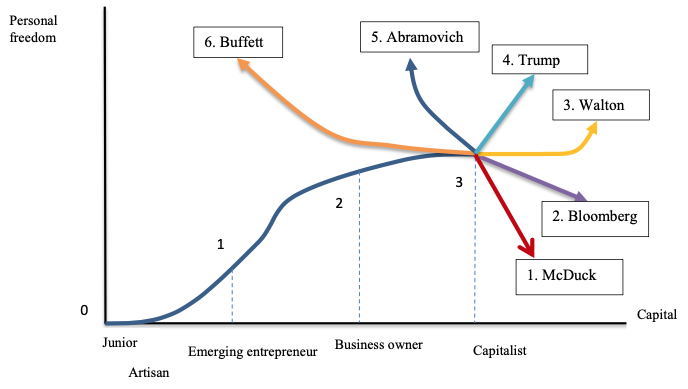

In ascending to the social stratum associated with the desired freedoms, the entrepreneur goes through typical stages that comprise the lifecycle of an entrepreneur. We present a graphic model of the lifecycle of an entrepreneur. The model rests on the two assumptions:

The fig.1 shows how the level of personal freedoms changes as the entrepreneur’s capital grows.

Fig. 1

The lifecycle (LC) of an entrepreneur

Successful entrepreneurs begin as juniors and, having gained capital and life experience and having gone through different stages, they become capitalists. At the capitalist stage, entrepreneurs are faced with a question what to do next. They have attained the desired level of freedom and independence. They do not have to work 24 hours a day to develop their business as they did before. We called this stage the ‘ramification point’. At this point, the single LC trend splits into many ramifying paths. Typical paths – called attractors – will be discussed below.

Entrepreneurs always begin as juniors, regardless of what age they were when they embarked on the path of entrepreneurship. Mark Cuban – the owner of the Dallas Mavericks – began his business career at 25 and Ray Kroc – the founder of McDonald's – at 52. Both, regardless of the starting age, were artisans when they started their businesses, yielded the first results, and worked alongside their employees. Both were managing their businesses and learning business as a craft. At the next stage, entrepreneurs are engaged solely in management, human resources, and finance. They do not work in production – they become managers. At this, point, they become emerging entrepreneurs (figure 1, point 1).

Out of the 486 respondents, 40.3% said that they had learnt entrepreneurship from their business partners, 19.4% from ‘parents and mentors’. This means that 59.7% of the respondents went through the ‘junior/artisan’ stage. Another 22.6% learnt business from ‘movies and books’, which can also be associated with the development stage in question.

Achieving point two (figure 1, 2) turns an emerging entrepreneur into a prosperous business owner. This stage of the LC is associated with the ownership of the desired basic material values and with a change in the initial motivation. The scale of the business is sufficient to meet all the needs of the entrepreneur and to ensure personal freedom, security, and health. The accumulated wealth is used to solve the problems of family and social responsibility and of self-fulfillment.

In growing richer and more mature, the entrepreneur achieves the third point (figure 1) – the stage of a capitalist. A capitalist is an entrepreneur whose capital is so substantial that it becomes financial rather than industrial, i.e. the capital is used across many industries to produce maximum returns.

We believe that this LC stage to be the ultimate achievement. After that, the entrepreneur is faced with the need to choose a different path of personal development. We call it the ramification point. As a rule, the entrepreneur chooses from six typical attractors.

Each of the attractors suggests either curbing freedom to increase capital gains or securing more freedom by resorting to different forms of capital management, ranging from donating capital to charity to leaving inheritance.

The first attractor consists in continued accumulation of wealth, accompanied by a reduction in contacts with the outer world. This way of conduct is called the McDuck attractor after the popular cartoon character. Personal freedoms start to shrink, since preserving and increasing a large capital require substantial personal efforts.

The second attractor suggests preserving and increasing capital under the management of other persons. A possible solution is going public. In this case, the capitalist will have to take on new, as a rule, social projects and thus to curb personal freedom. During his eight years in office as the mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg was receiving an annual salary of USD 1. This style of behavior is called the Bloomberg attractor.

The third attractor distinguishes entrepreneurs who place their families in charge of their companies. This path was chosen by Sam Walton – the founder of the world’s largest retailer, Walmart. Walton attained a new level of freedom and increased his capital by using the energy of his family. This is called the Walton attractor.

The fourth attractor. There are capitalists who strive to increase their capital through coming to political power. This was done by the Ukrainian oligarch Petro Poroshenko and, it seems, this is also the case of Donald Trump, whose rises and falls are rather well-known. This path is called the Trump attractor.

The fifth attractor. Many entrepreneurs who have reached the peak choose to retire and channel their energy into excessive consumption and all the kinds of “toys”. Such businesspersons spend their fortune on luxury goods, palaces, private jets, super-yachts, and sports clubs. This style is called after the Russian epitome – the Abramovich attractor.

The sixth attractor. Getting rid of most of the capital – settling for the accumulated wealth and donating the capital for charity – is another way to attain greater freedom. This path was chosen by Warren Edward Buffet, whose total net worth was estimated at USD 46.5 billion. In June 2010, Buffet announced that he would give away 75% of his wealth – approximately USD 37 billion – to five charities.

During the transformation from a junior to a capitalist, the entrepreneur’s attitude towards the tools and nature of entrepreneurship changes. When assigned to different LC stages, the characteristics of the entrepreneur, which might seem inconsistent otherwise, fall into place. Such assignment resolves contradictions found in the works of economists, psychologists, and sociologists focusing on entrepreneurship theory.

At the first – junior – stage of the lifecycle, entrepreneurs embark on the chosen path. They know little and have to learn. Juniors act according to their “limited knowledge and skills, i.e. human capital” and they are “moved by irrational optimism”. At the same time, juniors have “the knowledge of the market, people, and the economic situation that helps conduct business”. At this stage, entrepreneurs start giving preference to one or several business styles, since “the psychological makeup of an entrepreneur develops in early childhood. A major drive is gaining control of one’s body the way one’s parents taught them. In adults, this attitude transforms into a propensity for control over not only oneself and one’s performance but also one’s environment”. Achieving success requires self-control and control over the environment, which become “a basic characteristic of the psychological makeup of the entrepreneur, at least, at the first stage”.

After entrepreneurs have completed the first stage of apprenticeship, they embark on the path of conducting business independently as an “artisan”. At this stage, entrepreneurs acquire new characteristics. At the junior stage, they were protected from the environment by mentors and teachers. At the artisan stage, entrepreneurs have to adapt to the environment on their own to protect their businesses. “The area and nature of entrepreneurial activity is affected by a number of non-economic factors – ethics, religion, the way religious communities are organized, etc.” The artisan stage means that self-organization mechanisms are not used to full capacity and entrepreneurs throw themselves completely into their businesses. At this point, they believe in their uniqueness. Thus, “the behavior of entrepreneurs is not rational and it does not even tend towards rationality, since the cognitive faculties of a person – perception, memory, decision-making abilities, etc. – are limited. At this stage, entrepreneurs lack experience and expertise.” They cannot make right decision intuitively. At the same time, “the behavior of an entrepreneur is not rational because of the irrationality of the environment”.

Having gone through the organization stage, businesspersons enter the “emerging entrepreneur” stage. Entrepreneurs do not have to control all the technological, production, and economic processes anymore. There are working self-organization mechanisms. The new focus is the analysis of the environment, as well as the search for the best solutions in a changing world. All the capital can be channeled to solving these problems. At this stage, the entrepreneurs are distinguished by “pursuing economic activities in order to gain maximum profits against the background of maximum risks”. Entrepreneurs are ready to “provoke instability in the market to generate profits. Entrepreneurs are destroyers of stability”. However, alongside undermining stability, they “develop the economy with their capacity to initiate innovations and to create instability, thus triggering the natural selection mechanisms”. Owning a well-functioning business – a foundation for further growth, – entrepreneurs are ready to take the risk of creating a new non-standard business. Such endeavors require abandoning many preconceptions and breaking many established rules. Therefore, ‘successful entrepreneurs are those that are not burdened by social or cultural connections and ties. Freedom from such relations lets them launch highly lucrative but sometimes immoral projects”. This explains why “excessive parental control and rejection” – which translated into the entrepreneur’s self-control and control of the environment at the previous stage – leads to “ignoring the existing rules of conduct and undermining authorities”.

Having raised substantial capital through high-risk transactions and having enjoyed the stimulating excess of adrenaline, entrepreneurs become business owners. They have a substantial capital and they are scared of losing it if they continue high-risk transactions. Now, risk is a memory and a target for moralizing. At this stage, entrepreneurs prefer low-risk decisions. That is why researchers focusing on business owners argue: “the psychological makeup of the entrepreneur does not have a propensity for risk-taking”. However, if they have to make decisions under risk, “the level of risk taken depends solely on the entrepreneur’s self-esteem. The higher self-esteem, the more probable it is that the entrepreneur will opt for higher risks and vice versa.”

Choosing not to risk, business owners focus on stable projects. Such entrepreneurs “contribute to the inter-industry balance, since they are interested in long-term competitiveness. As decision-makers, business owners respond promptly to changes in the market.” Putting capitals into industries associated with the highest profits, business owners “facilitate economic self-regulation – market balance is restored through price and demand fluctuations”.

Such a cautious and low-risk game – a product of the entrepreneur’s wide experience and acute intuition – takes almost all business owners to the capitalist stage. Here, entrepreneurs are not engaged in a particular industry. Their principal tool is their own and loan capitals that they use to increase wealth. At this LC stage, entrepreneurs “seek nonequivalent exchange in the conditions of a monopoly and look for new projects”. Capitalists “invest easily in new industries in pursuit of maximum profits”. Such entrepreneurs “shape business cycles and find ways out of crises”.

Having a lot of time freed from business activities, they can make their childhood or even unconscious dreams come true – buy a football team, establish an eponymous research foundation, donate to charity, etc.

After examining the dynamics of the entrepreneur along the lifecycle, we would like to address the phenomenon of social entrepreneurship. This phenomenon has an immediate bearing on the LC. Social entrepreneurship is becoming increasingly popular. However, the academic community does not always distinguish between social entrepreneurship and such thoroughly studied objects as non-profit business, sponsoring, and social responsibility. Social entrepreneurship theory is emerging and the number of questions it poses is greater than the number of answers it gives.

As an academic term, the phrase “social entrepreneurship” was first used in 1991 in an article by Sandra Waddock and James Post titled “Social Entrepreneurs and Catalytic Change” (Waddock, 1991). Although the article did not attract much interest at the time, many works have been dedicated to social entrepreneurship after that. Moreover, universities have launched master’s degree programmes in social entrepreneurship. For instance, the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship and the Saïd Business School are operating at the University of Oxford. Social entrepreneurship is taught at the Goldsmiths, University of London. Similar programmes are offered at Roskilde University in Denmark and McGill University in Canada. American, French, and other universities teach social entrepreneurship. However, these programmes seem to serve a propagandistic function. Indeed, all the curricula include courses on strategic business modelling, planning and management, social networking and government relations, marketing, etc. However, none of them contains disciplines that have an immediate bearing on social entrepreneurship. An analysis of the curricula shows that the major difference between these programmes and, for instance, those in innovative entrepreneurship is that that the word “innovative” is replaced with the word “social”. The structure and selection of courses are the same.

This circumstance and an analysis of research works on social entrepreneurship suggest that economic science has no clear single definition of the phenomenon. There is no consistent theory of social entrepreneurship. Therefore, one can only speak of a concept of social entrepreneurship studies, which – as any other new concept – is criticized continuously and ubiquitously.

Any theory aims to explain an actual phenomenon. When explaining social entrepreneurship, researchers identify it with a certain static market phenomenon – an individual instance of entrepreneurship in the social goods market.

Some researchers believe that not all entrepreneurs are ready to and can engage in social entrepreneurship. To do so, they need a social mission, social goals, and profiting strategies that are in line with social interests (Austin, 2006; Zahra, 2009). Unlike a businessperson, an entrepreneur pursues maximum profits. This raises the question as to whether a person engaged in social business can be called an entrepreneur. Theory does not provide an adequate answer. Moreover, when giving a definition of “social entrepreneurship”, researchers have not so far been able to marry up the pursuit of maximum profits with offering social goods that often produce no profit at all.

Although social entrepreneurship has been discussed for over thirty years, there is still no single definition. The phenomenon is usually defined through listing its properties, which is indicative of a lack of a strong theoretical framework.

Nicholls and Cho analyzed some attempts to define social entrepreneurship: “For example, the Institute for Social Entrepreneurs (2005) defines social entrepreneurship as ‘the art of simultaneously pursuing both a financial and a social return on investment’ (the ‘double bottom line’), clearly enumerating the market oriented dimension of social entrepreneurship. Likewise, Alter (2000) defines social enterprise as a ‘generic term for a nonprofit enterprise, social-purpose business or revenue-generating venture founded to support or create economic opportunities for poor and disadvantaged populations while simultaneously operating with reference to the financial bottom line.” (Nicholls, 2008, p. 112).

Below, Nicholls and Cho presented their own vision: “We suggest that social entrepreneurship differs from other organizational forms primarily with respect to its social mission, its emphasis on innovation, and its general market orientation. Particular social entrepreneurship ventures will include these elements to differing degrees, but they are useful markers for mapping out the structure of the field.” (Nicholls, 2008, p.115).

Similarly, Alter did not give a clear definition of social entrepreneurship but rather listed the attributes of this phenomenon. This new socioeconomic activity combines an organization’s social purpose with entrepreneurial innovations and self-sustainability. At the same time, entrepreneurs should be committed to innovations, financial discipline, and procedures (Alter, 2006).

There have been attempts to interpret social entrepreneurship by means of a structural analysis (Choi, 2014; King, 2013). Such an analysis focuses on both the firm operating in the social services market and the social entrepreneur. Sometimes, authors provide a classification of the firm’s social product. Other researchers analyse the social service market, in which the entrepreneur competes. Some works center their classifications on social innovations, which – as many believe – distinguish an entrepreneur from a businessperson. A special focus is the staff of a social enterprise. However, the attempts to identify the distinguishing characteristics of a social entrepreneur do not yield systematic knowledge.

Some authors have viewed social entrepreneurship as an activity distinguished by a personal propensity for it. This means that not any entrepreneur can become a social one. Researchers that share these views argue that social entrepreneurs have the elevated feeling of responsibility for their activities. Such entrepreneurs are in a continuous search for opportunities to increase social welfare through creating new enterprises and new goods. Social enterprises seek to mitigate and solve social problems (Dees, 2007; Zahra, 2009). When adopting this approach to defining the social entrepreneur, researchers often overlook such crucial properties as propensity for risk-taking and gaining maximum profit.

There is no “absolute” entrepreneur and the market is composed of different concrete entrepreneurs with different mentalities and attitudes to business and the environment. However, some researchers attempt to distinguish the most stable types of social entrepreneurs. These are such types as the social bricoleur, the social constructionist, and the social engineer (Mair, 2006).

What do they stand for? Social bricoleurs are active across many social and economic spheres. They are ready to engage in any social business. Social constructionists conduct business by creating social constructs in the course of interpersonal interactions. Social engineers benefit from the whole spectrum of knowledge to streamline the process of creating, modernizing, and reproducing new social realities. They transform social institutions, values, and rules into business models.

Having borrowed the identified types from sociology, this classification raises a number of questions. For instance, sociology distinguishes between social constructivism and social constructionism. The former is aimed at interpersonal interactions and the latter at group processes. Does this mean that the classification should be supplemented with the “social constructivist” type? Even if it does, the above classification breaks a basic rule – the classification criterion changes in the course of grouping. Such a classification can be expanded infinitely. Indeed, if the bricoleur is distinguished as an entrepreneur active across all the sectors of the social goods market, the classification criterion is the market coverage. However, the distinguishing criterion for the social engineer who transforms social institutions into business models is the market tool. This means that the grouping criteria do not coincide.

An analysis of literature on social entrepreneurship gives a very vague picture of who the social entrepreneur is and what social entrepreneurship means.

A major research problem is combining two contradictory characteristics – the propensity for gaining profits and social pursuits, which warrant a certain degree of altruism.

We believe that the key to solving this problem is a dynamic approach to the phenomenon of entrepreneurship. Such an approach shows that the entrepreneur’s system of motives and incentives changes and evolves throughout the lifecycle. Therefore, a theory of social entrepreneurship requires using a special classification criterion – the type of the entrepreneur’s motive.

Almost all the authors who have addressed this problem stress that social entrepreneurs are distinguished by altruism, social responsibility, and a desire to change the society for the better. However, this is a general motive and it is rather difficult to identify its subtypes. Quite obviously, such distinguishing characteristics of the social entrepreneur as honesty, integrity, responsibility for business outcomes, and social responsibility towards the employees are neither new nor unique to the social entrepreneur (Lora, 2013). At the same time, it is difficult to marry up social responsibility, which suggests stability and low-risk decisions, and the entrepreneur’s propensity for risk-taking. This dilemma has been known since the times of J.-B Say.

All the contradictions are resolved by addressing the entrepreneur’s lifecycle model (see figure). For us, of special interest is the transition from the third (business owner) to fourth (capitalist) stage. At this point, the entrepreneur has almost joined the desired social stratum. Wealth translates into almost complete freedom and independence.

At the first stage of the lifecycle, the desire to ascend the social ladder is great. Researchers call this desire entrepreneurial potential. This stage is associated with maximum entrepreneurial activity – only personal moral and ethical attitudes can put a limit on the striving for profits. Entrepreneurs are ready to work round the clock and demand that their employees do the same.

At the end of the third stage, entrepreneurs turn into capitalists. They have broken into the desired social stratum and their entrepreneurial potential is close to zero. They do not have any incentive to overwork themselves or others. Such entrepreneurs have sufficient means to meet the needs of the highest level. At this ramification point, entrepreneurs have to select a certain way of conduct in view of a number of internal or external circumstances. These ways of conduct are called attractors. The Buffett attractor suggests a new level of freedom. In a free society, entrepreneurs who have accumulated substantial capitals and reached the ramification point often decide to give away a significant part of their personal wealth to different socially significant projects – establishing foundations and building hospitals, libraries, and stadiums. Such businesspersons engage in social entrepreneurship. The essence of social entrepreneurship lies in that liberating oneself from the earned and accumulated capital grants one a completely new freedom – the independence from capital.

Having embarked on the path of entrepreneurship, whose course is described by the above lifecycle, each person covers a different distance. At the capitalist stage, entrepreneurs have free capital, which they can use without inflicting damage on the business that once brought them their wealth. In each case, it is a different level of capital. For some, free capital equals one million dollars. For others, it is one hundred million dollars. Still, some will say that free capital means a billion dollars. Anyway, having engaged in social entrepreneurship, a member of any of these schools of thought will become a social entrepreneur.

Entrepreneurs with a free capital of one million dollars have enough means for small and medium social entrepreneurship whereas those with a billion dollars can invest in large social projects.

The above explains the diversity of social entrepreneurship types – entrepreneurs reach the ramification point at a different total net worth.

What is the difference between social entrepreneurship and sponsoring? A sponsor allocates funds meant for a socially significant project to a third person and thus loses control over these funds. Social entrepreneurship is a slightly different case. The entrepreneur retains control over the funds and starts a new social business. Such a business is an instance of charity, thus the entrepreneur demonstrates altruism, social responsibility, and a desire to change the society for the better.

Now we can define social entrepreneurship. It is an entrepreneurial activity distinguishing successful entrepreneurs who accept social responsibility towards the society and have means to implement this responsibility be creating a social business.

Any successful entrepreneur has to complete the arduous journey from an emerging businessperson to a capitalist who does not engage in entrepreneurship anymore.

In the course of this evolution, significant changes occur in the worldviews of entrepreneurs and their styles of conducting business. Nor do attitudes to competitors and employees stay the same. Despite their great diversity, these changes fit it a single model of the lifecycle of an entrepreneur.

This model proves instrumental in systematising the distinguishing characteristics of the entrepreneur that have been identified over many centuries of studying entrepreneurship. Sometimes, these characteristics are in conflict.

Considered in the framework of general dynamics of entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship is an activity that is pursued by businesspeople who have achieved ultimate success.

The entrepreneurial potential of social entrepreneurs is close to zero and their interests focus on charity and social goods. Social entrepreneurs are those who had strong moral and ethical attitudes at the beginning of their path.

Intrinsically moral entrepreneurs, having passed the stage when their principles were secondary to other considerations, return to their initial condition. Having reached the desired level of capital, such entrepreneurs start to adhere to their intrinsic moral principles and to show altruism and social responsibility.

A desire to change the society for the better stimulates successful entrepreneurs to engage in social businesses. In doing so, they demonstrate exceptional honesty and integrity, as well as social responsibility towards their employees.

Adizes I. Managing Corporate Lifecycles. The Adizes Institute Publishing, 2004. 460 p.

Alter S. K. Social enterprise models and their mission and money relationships. In A. Nicholls (Ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Social entrepreneurship: New models of sustainable social change. 2006. Р. 205 – 232.

Austin J., Stevenson H., Wei-Skillern J. Social or commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 2006, vol. 30 (1), pp. 1 – 22.

Brockhaus R. H. The psychology of the entrepreneur. In C. A. Kent, D.L. Sexton & K.H. Vesper (Eds.). Encyclopaedia of entrepreneurship. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1982. P. 39-56.

Cantillon R. Essays on the Nature of Commerce in General. Transaction Publishers, 2009. 188 p.

Chell E. The Entrepreneurial Personality: A Social Construction. Routledge, 2008. 320 p.

Choi N., Majumdar S. Social entrepreneurship as an essentially contested concept: Opening a new avenue for systematic future research. Journal of Business Venturing, 2014, vol. 29, pp. 363 – 376.

Cunningham J.A., O'Kane C. Technology-Based Nascent Entrepreneurship: Implications for Economic Policymaking. Springer, 2017. 312 p.

Dees JG. Taking Social Entrepreneurship Seriously: Uncertainty, Innovation, and Social Problem Solving. Society, 2007, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 163–172

Ivanova E., Gibcus P. The decision-making entrepreneur: Literature review. SCALES-paper N 200219, 2003. 41 p.

King D., Lawley S. Organizational Behaviour. OUP Oxford, 2013. 648 p.

Kirzner I.M. Competition and Entrepreneurship. University of Chicago Press, 1978. 246 p.

Lora E., Castellani F. Entrepreneurship in Latin America: A Step Up the Social Ladder? World Bank Publications, 2013. 208 p.

Marshall A. Principles of Economics, Vol. 1 (Classic Reprint). Fb&c Limited, 2017. 914 p.

Mair J., Martí I. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 2006, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 36 - 44.

Mullins J., D. Forlani. Perceived risks and choices in entrepreneurs’ new venture decisions, Journal of Business Venturing, 2000, vol. 15, pp. 305-322

Nicholls A., Cho A. Social entrepreneurship: The structuration of a field. Social entrepreneurship - new models of sustainable social change, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 99 - 118.

Odiorne G.S. The Human Side of Management. Lexington Books, 1990. 236 p

Quesnay Francois. Quesnay’s Tableau Économique. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016. 107 p.

Say J.-B. A Treatise on Political Economy. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008. 488 p.

Schumpeter J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Routledge, 2013. 460 p.

Zahra S., Gedajlovic E., Neubaum D., Shulman J. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search process, and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing, 2009, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 519 – 532.

Veblen T. Essays in Our Changing Order. Read Books Ltd, Literary Collections, 2014. 493 p.

Waddock S., Post J. Social Entrepreneurs and Catalytic Change. Public Administration Review, 1991, vol. 51, no. 5, pp 393 - 402.

Wärneryd K. E. The Psychology of Saving: A Study on Economic Psychology. E. Elgar, 1999. 389 p.

1. PhD, Associate Professor of The Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, td-semia@mail.ru

2. Doctor of Science, Professor, Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, sergey@svetunkov.ru