Vol. 40 (Number 35) Year 2019. Page 10

FEITÓ, Duniesky 1; PORTAL, Malena 2 & BERNAL, Blanca E. 3

Received: 28/06/2019 • Approved: 02/10/2019 • Published 14/10/2019

ABSTRACT: The objective of this study is to analyze the behavior of micro-enterprises from a gender perspective, through the analysis of possible differences associated with the figure of the entrepreneur and the characteristics of this type of business. For this, approach the application of nonparametric statistics for a sample of 1478 microenterprises is used. The results reflect differences in terms of age, education and experience. In turn, the micro-enterprises run by women are smaller, less profitable, and mostly family. |

RESUMEN: El objetivo de este estudio es analizar el comportamiento de las microempresas desde una perspectiva de género, a través del análisis de las posibles diferencias asociadas con la figura del empresario y las características de este tipo de negocio. Para ello, se utiliza la aplicación de estadísticas no paramétricas para una muestra de 1478 microempresas. Los resultados reflejan diferencias en términos de edad, educación y experiencia. A su vez, las microempresas dirigidas por mujeres son más pequeñas, menos rentables y en su mayoría familiares. |

In recent decades worldwide, interest and commitment have increased in relation to the establishment of gender equality, equity and the fight against any form of discrimination against women from different areas, be it political, economic or social. This has led to the design of strategies by nations who search to reduce the gaps and to establish priorities within their own contexts in order to advance towards gender parity.

According to data from the Global Gap Gender report published in 2017 where the information of 144 countries on gender issues is analyzed, the gap between men and women with access to health services has decreased by 96% and more than 95% in educational achievements. However, according to this report, the gaps in economic participation and political empowerment remain wide. In the case of Mexico, who occupies the 81st position, the main challenges are found in the health, survival and salary equality indices. In this same order and according to the study carried out by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2017), it is pointed out that in order to increase Mexican GDP by at least 0.2 percentage points annually, it is necessary to reduce by half the gender gap in labor force participation.

Given this scenario, different governmental institutions in the country have taken on the task of carrying out important efforts to promote the economic and political empowerment of women. Some examples are the inclusion of the gender perspective in the National Development Plan 2013-2018, and the implementation of the program to strengthen municipal policies for equality and equity. However, despite the efforts made, the gaps remain worrisome; a reflection of this is that in 2017 only 4.7% of large companies in the country had more than three women on their board of directors, compared to 47% in the other OECD countries (Ramos, 2017b).

These negative effects are even more alarming in the context of smaller enterprises. In this sense, and according to data from the National Survey of Occupation and Employment (ENOE), between 2005 and 2015 the proportion of female employers heading small establishments decreased from 15.1% to 8.9%. This same survey indicates that for the third quarter of 2016, 20.8 million women aged 15 and over were part of the economically active population in the country with a participation rate of 43.9%, lower than the economically active male population. In terms of income, the self-employed Mexicans women earn 47% less than the self-employed men, a difference greater than 33% in average of the rest of the countries that belong to the OECD (Ramos, 2017a).

For the Mexican case, empirical studies in relation to the issue of gender inequality are associated to a greater extent to disciplines such as sociology, or psychology linked to the problems faced by women in issues such as violence, vulnerability, abuse, motherhood, identity or inclusion in society (Mora, 2017; Ramírez and Díaz, 2017; Frías and Agoff, 2015; Ruiz et al., 2014; Rodríguez and Lugo, 2014; De León, 2014). Derived from this, there is little research aimed at studying the possible differences between women and men in terms of skills and training to manage a business, individual typologies, growth expectations, as well as the characteristics of the enterprises they run.

In this way, and with the purpose of deepening through this problem in the business world, the objective of this paper focuses on trying to explain the behavior of micro-enterprises in Mexico from a gender perspective, where possible differences associated with the figure of the entrepreneur and the enterprises that they direct are analyzed. To this end, a quantitative methodology is applied, combining the descriptive and correlational approach based on the application of non-parametric statistics. The document is structured in four sections: in the first one, a review of the literature is developed, which includes the previous empirical studies. Subsequently, in section two the methodology is exposed with information on the study sample, the measurement of the variables and the approach of the research hypotheses. In the third section the analysis of the results is presented, and finally, in the fourth section the main conclusions of the study are addressed.

The review of the literature reflects a change in the conceptualization of gender and entrepreneurship during the last 30 years. According to Henry et al. (2015), the 1980s marked the beginning of research articles on women's entrepreneurship, with an evolution in the characteristics of studies in the area, going from purely descriptive and devoid of theoretical approach explorations, to the effort to incorporate them within highly informed conceptual frameworks. From this approach, there is a widely accepted categorization in the historical development of feminist thought that encompasses three schools: feminist standpoint theory (FST); gender as a variable (GAV) and post-structural feminism (PSF).

The FST theory identifies a particular social situation as epistemologically privileged, assumes that women have unique experiences as women and, therefore, the preferential right of interpretation with respect to knowledge about them and their conditions. Genealogy, from a feminist perspective, allows a different representation of women, these do not become simple objects of knowledge but in subjects of discourse, which overcomes the hetero-designation that was established as a norm and rescues the knowledge of women, traditionally marginalized by science and the academy (Restrepo, 2016).

For its part, the gender approach as a variable is a theory that is based on incorporating the specification of gender as an equivalent to sex where the presence and conditions of women are visible. In the conceptualization of sex and gender, there is an important distinction that points out the difference between the two, the term sex refers to the biological basis of the differences between men and women. On the other hand, and according to González (2001), the term gender refers to the set of contents or meanings which each society attributes to sexual differences.

Unlike the previous points of view, the post-structuralist school uses a more accurate definition of the word gender, referring to social practices and representations of femininity or masculinity, based on the assumption that gender is constituted socially and culturally (Ahl, 2006). From this perspective, studies have adapted the assumptions of these theories to the analysis of variables associated with the business practice. An example of this is the research of Saavedra and Camarena (2015), who address the theory of liberal feminism and the theory of social feminism, from examining the differences in the business performance of businesses based on the gender of the entrepreneur. In the case of the theory of liberal feminism, they point out that enterprises run by women have a lower performance due to the discrimination that exists in terms of access to resources that are important for the development of the enterprise, such as education or experience in business or capital. The theory of social feminism, in turn, argues that men and women are different by nature, and therefore women have a different approach to their business since they have other attitudes and values.

These ideas are supported by Herrera et al. (2016), by stating that the development of authority, control, achievement of results and leadership are typical of male behavior; whereas cooperation, protection or interpersonal dependence are characteristic of female behavior. However, these authors argue that there are other aspects that conceive that professional differences and in education make women more participatory and have more democratic decision processes, for which they are attributed a more interactive leadership, aimed at stimulating the participation and self-esteem of others and be more socially sensitive.

In the same way that the schools of thought identify the theoretical foundations that try to explain the differences in the performance of the businesses through the figure of the entrepreneur, in the empirical studies the classification of the factors that affect the performance of the enterprises that they run is observed. At the individual level, the factors most considered are education and experience, the last one seen in different ways, such as experience in management, in business, in work time and also individual experience, together with personal characteristics such as age, business skills, level of self-confidence and priorities in the administrative tasks (Cabrera and Mauricio, 2017).

Likewise, it has been possible to corroborate those women who are business owners have fewer years of managerial and business experience, and, in turn, gain experience in their own enterprise and not as salaried employees. To this is added that, on occasion, women face a disadvantaged position due to labor segregation, which reflects the different expectations about gender roles, and, in general, women entrepreneurs create their business when they are younger, hence the profile of older entrepreneurs is associated with greater experience and credibility (Marlow and Carter, 2004; Marlow, 2002; Shim and Eastlick, 1998; Cowling and Taylor, 2001; Shaw et al., 2005).

Regarding the educational levels of women, the efforts of countries to achieve gender equality have led to the improvement of this indicator as a result of national education systems. In the case of Mexico, the illiteracy rate of women aged 15 and over has been reduced from 8.1% in 2010 to 6.5% in 2015, as a result of the increase in basic education coverage and the programs proposed by the National Institute of Education for Adults (INEA). Regarding the level of schooling, in the period 2010-2015 there is a significant increase in the percentage of the female population from 15 to 19 years whose minimum education was completely secondary, with a growth of 6.6%, however, compared to the behavior for the male sex, this has been greater by 8%. At the levels of pre-university and superior education, even though there has been an increase in the proportions of the population aged 20 to 24 that had at least an approved grade of these school levels, the gap between women and men continues to be present with some advantage for the last group.

According to Elizundia (2015), there are more and more women who complete higher education, but in the influence of a traditional culture and established roles, women continue to have functions of family support and child care which prevents them from dedicating more time to administrative activities and acquire enough experience to operate a business successfully. On the other hand, in the analysis of the educational level for the composition of the business stratum in Mexico, the National Survey of Productivity and Competitiveness (ENAPROCE, for its acronym in Spanish, 2015) shows that micro-enterprises have the highest percentages of personnel employed with basic education and without schooling with 55.4% compared to small and medium enterprises.

In the same way that we have sought to identify the differentials in business performance associated with factors of an individual type, there are other studies that analyze variables related to the characteristics of the enterprise that these direct. In this case, it has been possible to identify the influence of factors related to the sector to which they belong, to the size, the seniority, the type of enterprise and the economic results (Briozzo et al., 2017; Elizundia, 2015; Ernst and Young, 2009; Díaz and Jiménez, 2010; Rogers, 2005; De Martino and Barbato, 2003; Carter et al., 2001; Boden, 1999; Shim and Eastlick, 1998; Moore and Buttner, 1997).

The derivations of these studies show that, in general, women's enterprises face certain structural disadvantages such as a smaller dimension, less seniority and a concentration in less profitable sectors. Its presence is, to a greater extent, concentrated in small-sized businesses and traditional low-growth sectors, mainly services and retail trade, with structures of a single owner. These characteristics are associated with the amounts of capital invested which, for these cases, are of lower value compared to those employed by enterprises started by men. For this reason, these businesses tend to be less attractive to the providers of funds, which translate into a lower use of external financing by women.

In relation to the type of family business, it is observed that women have a greater role in this group compared to men, which has been argued based on the theory that women are more interested in conserving heritage and preservation of the family unit, a fact that is attributed to the importance that women give to achieving a balance of their professional and personal roles.

In terms of economic results, studies indicate that in enterprises run by men there is a greater capacity to transform financial capital into income and to materialize their growth intentions in the short term. When initiated with more capital, performance levels are higher, while enterprises run by women have lower investments in assets. In turn, these studies show that women have a different conception regarding the growth goals of their business, with a less directed orientation towards economic achievements, since they establish maximum limits for the size of their enterprise from which they prefer not to expand (Cliff, 1998). This behavior affects the income level and the general performance of this business.

In accordance with the objective of the study, quantitative research was developed in which the descriptive and correlational approach is combined. The total universe of analysis consists of 38,000 micro-businesses from the city of Tijuana, Baja California registered in the database of the National Statistical Directory of Economic Units (DENUE, for its acronym in Spanish). For the determination of the sample size, a margin of error of 2.5% and a confidence level of 95% was established, which yielded a total sample of 1,478 micro-businesses. The design of the fieldwork was carried out through a stratified random sampling according to the different sectors of economic activity defined by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography of Mexico (INEGI, for its acronym in Spanish). In this way, 475 enterprises from the service sector were studied, 477 from the commerce sector, 339 from the manufacturing sector and 193 from the construction sector. The information was collected between the months of August and November of 2017 through a survey specifically addressed to the managers of these enterprises. Table 1 shows a description of the variables that were analyzed as part of the study.

Table 1

Operationalization of the variables

Construct |

Variable |

Definition |

Measurement scale |

Characteristics of the business owner |

Age |

Age in years of the owner |

Quantitative |

Experience |

Experience in years of the owner of the business in the labor market |

Quantitative |

|

Schooling |

Level of schooling of the business owner. Six levels are established, 1-no schooling, 2-primary, 3-secondary, 4- pre-university, 5-bachelor, 6-postgraduate |

Ordinal |

|

Gender |

It refers to the sex of the business owner. Takes value 1- Female and 2 - Male |

Nominal |

|

Characteristics of the enterprise |

Type of enterprise |

Takes value 1 - if it is a family business and 2- if it is non-family |

Nominal |

Sector |

Referred to the sector where the enterprise operates. It takes value 1- services, 2- commerce, 3-manufacturing and 4- construction |

Nominal |

|

Seniority |

Years since the start of the enterprise until the study date |

Quantitative |

|

Size of the enterprise |

It is defined as the number of workers currently operational |

Quantitative |

|

Design of the enterprise |

Average monthly value of sales in Mexican pesos. Take 1 -0-5000, 2- 5000-10000, 3 >10000 |

Interval |

Source: Own elaboration

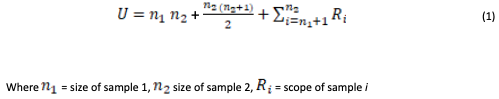

The combination of two nonparametric tests, the Mann-Whitney U test (U) and the Pearson's chi-squared test (χ²) were used to analyze dependency relationships between the variables. The Mann-Whitney U test is a statistical method that allows analyzing differences between a continuous dependent variable and an independent variable of two-level categorical type. The null hypothesis refers to the fact that the medians of the population from which both samples come are the same. It is further assumed that the sample data are randomized from two independent observation groups and the distribution of the population of the dependent variable for the two groups shares a similar unspecified form, although with possibilities of differences in the central tendency measures. The hypothesis test is based on the significance of the Mann-Whitney statistic (U):

Taking into account the above, the following research hypothesis are defined:

H01: There are no significant differences in the work experience of women and men micro-entrepreneurs.

H02: There are no significant differences in the educational level of women and men micro-entrepreneurs.

H03: There are no significant differences in the age of women and men micro-entrepreneurs.

H04: There are no significant differences in the size of micro-enterprises run by women and men.

H05: There are no significant differences in the age of micro-enterprises run by women and men.

H06: There are no significant differences in the performance of micro-enterprises run by women and men.

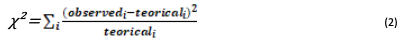

On the other hand, the Pearson's chi-squared test (χ²) allows studying the association between two categorical variables and measures the discrepancy between the observed and theoretical distribution (goodness of fit), indicating to what extent the differences between both are due to chance in the hypothesis contrast. The null hypothesis (H0), that there is no relationship between the two variables, is rejected only when the calculated value of the test statistic is greater than the critical value of the Chi-square distribution with the appropriate number of degrees of freedom. To calculate the statistical (χ²), the following expression is used:

To evaluate if there is an association between the variables, we estimate the probability of obtaining a Chi-square value, which is as large as or, larger than that calculated from the cross-tabulation. An important characteristic of the Chi-square statistical is the number of degrees of freedom (d.f.) associated with it. In general, the number of degrees of freedom is equal to the number of observations minus the number of limitations needed to calculate a statistical term. If, when calculating the values of the expression χ², which is the difference between the observed and the expected, we surpass a certain critical value, it is accepted that the differences found are too great to be explained by chance. This test leads to formulate the following hypotheses:

H07: There is no relationship between the sex of the entrepreneur and the sector to which the micro-enterprise belongs.

H08: There is no relationship between the sex of the entrepreneur and the family character of the micro-enterprise.

To begin with the discussion of the results, the descriptive analysis of the variables used in the study is presented. In this sense, and according to the statistics obtained, the highest percentage of the enterprises analyzed (73%) are headed by men, the average age of the owners of these businesses is 45 years, with previous experience in the labor market of 14 years. In terms of educational level, 3.7% of the sample has no schooling, 13.3% has a primary level, 25% completed secondary education, 30.1% pre-university, 22.8% have a bachelor's degree and the remaining 5.1% have a postgraduate.

In relation to the variables related to the characteristics of the enterprise, it was found that on average these economic units have 7 workers and have about 13 years, operating in the market. In terms of sales, 7.4% of the sample has incomes lower than 5,000 pesos per month, 28.5% between 5,000 and 10,000 pesos and 64.1% perceive revenues higher than 10,000 pesos per month.

Table 2 shows the results of the Mann-Whitney test, where possible differences between women and men are analyzed for variables associated with the characteristics of the enterprises and with their own individual capacities. The results show that for all the analysis variables there are significant differences in the medians of both groups.

Table 2 shows the results of the Mann-Whitney test where possible differences between women and men are analyzed for variables associated with the characteristics of the enterprises and with their own individual capacities. The results show that for all the analysis variables there are significant differences in the medians of both groups.

Table 2

Statistics Mann-Whitney test

Variables |

Mann-Whitney U |

Asymptotic Significance (bilateral) |

Average range |

|

Man |

Woman |

|||

Size of the enterprise |

190379.500 |

.000* |

767.89 |

674.41 |

Seniority |

190607.000 |

.000* |

767.68 |

674.97 |

Age |

196394.500 |

.003* |

762.32 |

689.33 |

Work Experience |

185388.000 |

.000* |

772.50 |

662.02 |

Schooling |

194861.500 |

.001* |

763.74 |

685.53 |

Performance |

192387.500 |

.000* |

766.03 |

679.39 |

*Significant p-value

Source. Own elaboration, based on

the results of the methodology.

Likewise, and according to the results of the Pearson's chi-squared statistical value, it is confirmed that there are relations of dependence between the sex of the owner of the business and the sector in which the enterprises are developing, as well as with the type of enterprises that they direct (See table 3).

Table 3

Results of the Pearson's

Chi-square test

Variables |

Category |

Gender |

Pearson's Chi-square |

Asymptotic Significance (bilateral) |

|

Female |

Male |

18.94a |

0.00* |

||

Sector |

Service |

145 (36.0 %) |

330 (30.5 %) |

||

Trade |

137 (34.0 %) |

340 (31.5 %) |

|||

Manufacturing |

93 (23.1 %) |

246 (22.8 %) |

|||

Construction |

28 (6.9 %) |

165 (15.3 %) |

|||

Type of enterprise |

Family |

246 (61 %) |

508 (47 %) |

23.18b |

0.00* |

Non-family |

157 (39 %) |

573 (53 %) |

|||

a 0% of the boxes have an expected frequency of less than 5

b 0% of the boxes have an expected frequency of less than 5

* Significant p-value

Source: Compiled by the authors, based on the results of the methodology.

The contrast statistics show that women have work experience and an educational level lower than that of men, which allows rejecting hypothesis H01 and H02. These results coincide with those obtained by Stošić (2017); Fairlie and Robb (2009); Verheul and Thurik (2001) and Boden and Nucci (2000), who analyze a group of micro and small enterprises in the Republic of Serbia and find statistically significant differences with respect to the field of education, the existence of management and previous entrepreneurial experience, with favorable results for male entrepreneurs. This behavior is a reflection of the incidence of social and cultural stereotypes that significantly limit the freedom of representation of women in the educational and business area, regardless of the region or country in question.

In the Mexican context, there is still a strong rootedness in the society where women must prioritize their family responsibilities over other interests such as work and professional development, which brings with it inequalities in labor segregation, as well as in educational levels, giving some advantage to the male sex. Under these conditions, the female microentrepreneurs are limited to being able to obtain a previous work experience as employees when they start their business, as well as having a higher degree of completed schooling.

In relation to age, statisticians show that women microentrepreneurs are younger compared to men, which makes it possible to reject hypothesis H03. The behavior of this variable can be explained by the increase in the early peak of fertility and the number of single mothers in Mexico. Given this phenomenon, the high demand to obtain a source of income that allows them to support their families has forced Mexican women to be in need of starting from an early age. According to the National Survey of Occupation and Employment (ENOE, for its acronym in Spanish, 2017), 48.4% of female microentrepreneurs have 3 or more children, and 33.8% are heads of households. On the other hand, of women aged 12 and over with at least one child born alive in 2015, 27.8% exercised their motherhood without a partner and of this 6.5% were single mothers. Faced with these scenarios, the responsibilities and economic obligations as heads of the family become one of the main motivations that affect the growing participation of women in the micro and small business sector.

With respect to the variables associated with the characteristics of the enterprises, the statistics show that the micro-enterprises run by women are smaller, less senior and have a lower performance in relation to the enterprises that are run by men; these arguments allow rejecting the H04, H05 and H06 hypotheses. In the same way, the statistical tests reflected in Table 4 corroborate the existence of a dependency relationship between the sex of the entrepreneur, the sector to which the micro-enterprise belongs and the family character of the same, which makes it possible to reject hypotheses H07 and H08. The results show that the highest percentages (36%) of the enterprises run by women are in the service sector. Likewise, it is confirmed that 61% of micro-enterprises run by women are family members, in contrast to 47% for men.

These results correspond to the evidence found by Briozzo et al. (2017); Hoffmann et al. (2014); Poon et al. (2012); López et al. (2011) and Loscocco et al. (1991), who reveal that the presence of women entrepreneurs is to a greater extent concentrated in small businesses and in traditional sectors, mostly service activities, with low growth and also less profitable. In turn, Meroño and López (2012) state that this distinctive feature is due to the fact that the service sector requires less complexity in activities and commercialization; in addition to that, women have the condition of offering a better service to the client because they are more methodical when carrying out their activities, especially when it comes to providing a service. These arguments represent to a large extent the Mexican micro-enterprise fabric, where 95.3% of the total economic units of this segment are grouped in the service sector, with female heads in 4 out of ten of these enterprises (Economic Census, 2014).

In relation to the presence of women in family-type enterprises and according to Briozzo, Albanese and Santolíquido, (2017), this phenomenon responds to a large extent with the role and responsibility that in the family environment is given to women, where a greater interest prevails in the preservation of the unity and the familiar patrimony, as well as in the generation of spaces of familiar communication. Similarly, there are studies that corroborate that women entrepreneurs in Mexico tend to invest their earnings more in education, health, and welfare when these things are in favor of their families (Elizundia, 2015).

Around the results found there is a group of authors who coincide in highlighting that the growth of the enterprises, as well as their survival, lies on the figure of the owner and depend to a large extent on the skills, experiences and social connections that the owner possesses (Cannela et al., 2009; Hambrick and Mason, 1984). In this regard, it is argued that for women, entrepreneurial activity is more difficult because it requires a double responsibility, on the one hand, those related to the home, and on the other, the obligations of the business itself. This entails that the interests are directed to the search of a balance between both commitments, giving priority to family tasks and, therefore, they have less time to dedicate themselves to the administration of the business. This act implicitly suggests that the growth goals established by the female microentrepreneurs are of smaller scope, that is, short-term goals with slow and stable growth rates, which is reflected in the number of workers as a measure of growth. These tendencies have been corroborated in previous studies carried out by Verheul, 2005; Collins et al. (2004); Fasci, and Valdez, (1998).

The investigation corroborated that in the case of Mexico there are significant differences in the performance of micro-businesses led by women and men, which are determined by factors associated with the figure of the entrepreneur and the characteristics of the enterprises they run. These results impact negatively in different areas not only from the moral and social point of view but also economically. Various institutions and international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the OECD have stated on multiple occasions that equality between men and women is in itself an important development objective, but the economic participation of women is also crucial for production, exports, diversification and a more equitable distribution of income, which leads to greater sustainable and inclusive growth.

In particular, the increase in the participation of women in the labor force can have significant macroeconomic benefits. If the countries of Latin America increase female labor participation to the average level of the Nordic countries (which is around 60%), the GDP per capita could rise up 10%. On the other hand, closing gender gaps in education increases the reserve of human capital and talent, which is fundamental for technological adoption and innovation, as well as increasing a country's ability to create and execute new ideas (IMF, 2016).

In the case of Mexico, these benefits could be upward, taking into account that there is a greater participation of women in the micro-enterprise fabric, which in turn constitutes the largest number of economic units at a national level compared to small, medium and large enterprises, hence the importance of encouraging and supporting the incubation of women's ventures with greater access and inclusion.

These pieces of evidences drive the need for developing countries such as Mexico to implement good practices in the search for gender equality that reforms the conditions for women's insertion in the labor market and guarantees access to services and equal opportunities. These scenarios will offer Mexican women the opportunity to develop their potential and participate in the economic life of the country with greater transparency. The extraordinary ability of women to self-employ and adapt to their needs, as well as having a great entrepreneurial spirit and a more interactive leadership, are conditions that favor the generation of jobs, productivity and the diversification of the economy.

This research seeks to contribute and deepen the empirical discussion about performance and business practice from a gender perspective in Mexico. Likewise, we seek to strengthen the information on the problem in order to contribute to the development of public policies that translate into greater benefits for women microentrepreneurs.

Ahl, H. (2006). “Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5): 595-621.

Boden, R. & Nucci, A. (2000). “On the survival prospects of men’s and women’s new business ventures”, Journal of Business Venturing, 15(4): 347-362.

Boden, R. (1999). “Flexible working hours, family responsibilities and female self-employment”, American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 58(1): 71-84.

Briozzo, A., Albanese, D. & Santolíquido, D. (2017). “Gobierno corporativo, financiamiento y género: un estudio de las pymes emisoras de títulos en los mercados de valores argentinos”, Contaduría y Administración, 62: 339-357.

Cabrera, E. & Mauricio, D. (2017). “Factors affecting the success of women’s entrepreneurship: a review of literature”, International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 9(1): 31-65. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-01-2016-0001.

Cannella, B., Finkelstein, S. & Hambrick, D. (2009). “Strategic Leadership: Theory and Research on Executives”, Top Management Teams and Boards. London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Carter, S.; Anderson, S. & Shaw, E. (2001). “Women business ownership: A review of the academic, popular and internet literature”,Report to the Small Business Service, RR 002/01.

Cliff, J. (1998). “Does one size fit all? Exploring the relationship between attitudes towards growth, gender, and business size”, Journal of Business Venturing, 13: 523-542.

Collins, C., Gordon, I. & Smart, C. (2004). “Further evidence on the role of gender in financial performance”, Journal of Small Business Management, 42(4): 395-417.

Cowling, M. & Taylor, M. (2001). “Entrepreneurial women and men: two different species?” Small Business Economics, 16: 167-175.

De León, M. (2014). “Niños, niñas, y mujeres: Una amalgama vulnerable”, Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, 12(1): 105-119.

De Martino, R. & Barbato, R. (2003). “Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators”, Journal of Business Venturing, 18: 815 – 832.

Díaz, C. & Jiménez, J. (2010). “Recursos y resultados de las pequeñas empresas: nuevas perspectivas del efecto género”, Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la empresa, 42: 151-176.

Elizundia, M. (2015). “Desempeño de nuevos negocios: perspectiva de género”, Contaduría y Administración, 60: 468–485.

Ernst & Young (2009). “The Groundbreakers series: driving business through diversity”, USA: EGYM Limited, Retrieved from: http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Scaling_up_-_Why_women-owned_businesses_can_recharge_the_global_economy_-_new/$FILE/Scaling_up_why_women_owned_businesses_can_recharge_the_global_economy.pdf (Consulted on April 21, 2018).

Fairlie, R. & Robb, A. (2009). “Gender differences in business performance: evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey”, Small Bus Econ, 33: 375–395. DOI 10.1007/s11187-009-9207-5.

Fasci, M. & Valdez, J. (1998). “A performance contrast of male- and female-owned small accounting practices”, Journal of Small Business Management, 36(3): 1-7.

Frías, S. & Agoff, M.C. (2015). “Between support and vulnerability: Examining family support among women victims of intimate partner violence in México”, Journal of family violence, 30(3): 277-291.

González, M. J. (2001). “Algunas reflexiones en torno a las diferencias de género y la pobreza”, En Tortosa, J. M. (coord.). Pobreza y perspectiva de género, (pp. 87-112). España: Icaria.

Hambrick, D. (2007). “Upper Echelons Theory: An Update”.The Academy of Management Review, 32 (2): 334343.

Hambrick, D.& Mason, P. (1984). “Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers”, Academy of Management Review, 9(2): 193206.

Henry, C., Foss, L. & Ahl, H. (2015). “Gender and entrepreneurship research: A review of methodological approaches”, International Small Business Journal: 1-25. DOI: 10.1177/0266242614549779

Herrera, J., Larrán, M., Lechuga, M. & Martínez, D. (2016). “Responsabilidad social en las pymes: análisis exploratorio de factores explicativos”, Revista de contabilidad, 19(1): 31-44.

Hoffmann, A., Junge, M. & Malchow, N. (2014). “Running in the family: parental role models in entrepreneurship”, Small Business Economics, 44(1): 79-104.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI (2015). “Encuesta Nacional sobre Productividad y Competitividad” ENAPROCE, Retrieved from: http://internet.contenidos.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos//prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/nueva_estruc/promo/ENAPROCE_15.pdf (Consulted on May 28, 2018).

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI (2017). “Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo” ENOE, Retrieved from: http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/enchogares/regulares/enoe/ (Consulted on May 28, 2018).

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI (2018). “Directorio Nacional de Unidades Económicas” DENUE, Retrieved from: http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/denue/ (Consulted on May 28, 2018).

López, M., Gómez, G. & Betancourt, J. (2011). “Factores que influyen en la participación de la mujer en cargos directivos y órganos de gobierno de la empresa familiar colombiana”, Cuadernos de Administración, 24(42): 253–274.

Loscocco, K.A., Robinson, J., Hall, R.H. & Allen, J.K. (1991). “Gender and small business success: An inquiry into women’s relative disadvantage”, Social Forces, 70(1): 65-87.

Marlow, S. (2002). “Self-employed women: A part of or apart from Feminist Theory?” Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 2(2): 83-91.

Marlow, S. & Carter, S. (2004). “Accounting for change: Professional status, gender disadvantage and self-employment”, Women in Management Review, 19(1): 5-16.

Meroño, Á. & López, C. (2012). “La empresa familiar y el acceso femenino a la gerencia empresarial”. En Monreal, J., Sánchez, G. (coord.), “El éxito de la empresa familiar”. La relación entre negocio y familia, Madrid: Civitas: 235-275.

Moore, D. & Buttner, E. (1997). “Women’s Organizational Female Business Owners: An Exploratory Study”, Journal Small Business Management: 18- 34.

Mora E. (2017). “Identidades femeninas desde el cuerpo y la violencia: Sangre en el desierto”, de Alicia Gaspar de Alba. Confluencia: Revista Hispánica De Cultura Y Literatura, 3(1): 76-90.

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos, (2017). “Building an Inclusive México, Policies and Good Governance for Gender Equality”, OECD Publishing, París. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/centrodemexico/medios/Estudio%20G%C3%A9nero%20M%C3%A9xico_CUADERNILLO%20RESUMEN.pdf

Poon, J., Thai, D. & Naybor, D. (2012). “Social capital and female entrepreneurship in rural regions: evidence from Vietnam”, Applied Geography, 35(1/2): 308-315.

Ramírez, D. & Díaz, M. (2017). “Los efectos de la política de prevención del crimen y la violencia en México”, Revista CIDOB D´afers Internacionals, 116: 101-128.

Ramos, G. (2017a). “El empoderamiento económico de las mexicanas”, Retrieved from: http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/entrada-de-opinion/articulo/gabriela-ramos/nacion/2017/07/24/el-empoderamiento-economico-de-las (Consulted on May 9, 2018).

Ramos, G. (2017b). “Mujeres en México, el talento olvidado”, Retrieved from: http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/articulo/gabriela-ramos/nacion/mujeres-en-mexico-el-talento-olvidado (Consulted on May 17, 2018).

Restrepo, A. (2016). “La genealogía como método de investigación feminista”, En Blazquez, N. y Castañeda, M. P. (coordinadoras), Lecturas críticas de investigación feminista, México: Universidad Autónoma de México, Centro de investigaciones interdisciplinarias en ciencias y humanidades, Programa de posgrado en estudios latinoamericanos, Red mexicana de ciencia, tecnología y género, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología: 23-42.

Rodríguez, R. & Lugo, D. (2014). “Análisis de la discriminación salarial por género en Saltillo y Hermosillo: un estudio comparativo en la industria manufacturera”, Nóesis: Revista De Ciencias Sociales Y Humanidades, 23(46): 80-113.

Rogers, N. (2005). “The impact of family support on the success of women business owners”, en Fielden, S., Davidson, M. (eds.), International Handbook of Women and Small Business Entrepreneurship, Chetenham (UK): Edward Elgar: 91-102.

Ruiz, M., Arenas, L., Bonilla, P., Valdez, R., Rueda, C. & Hernández, I. (2014). “Gender and physical activity in Mexican women with experience of migration to the USA”, Revista De Salud Pública, Bogotá, Colombia, 16(5): 709-718.

Saavedra, M. & Camarena M, (2015). “Diferencias en la competitividad de las empresas según el género del director”, Neumann Business Review, 01(02): 86 -73

Shaw, E., Carter, S., Lam, W. & Wilson, F. (2005). “Social Capital and accessing finance: the relevance of networks”, Paper presented at 28th ISBE Conference, Blackpool, UK.

Shim, S. & Eastlick, M. A. (1998). “Characteristics of Hispanic female business owners: an exploratory stud”, Journal of Small Business Management, 36(3): 18-35.

Stošić, D. (2017). “Diferencias en el capital humano de mujeres y hombres empresarios - Pruebas de la República de Serbia”, JEEMS, 22(4): 511 – 539.

Verheul, I. & Thurik, R. (2001). “Start-up capital: does gender matter?” Small Business Economics, 16(4): 329-345.

Verheul, I. (2005). “Is there a female approach? Understanding gender differences in entrepreneurship”, Doctoral dissertation Erasmus University Rotterdam.

1. Professor -Investigator, Faculty of Accounting and Administration, Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico. duniesky.feito.madrigal@uabc.edu.mx

2. Professor -Investigator, Faculty of Accounting and Administration, Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico. mportal@uabc.edu.mx

3. Professor -Investigator, Faculty of Accounting and Administration, Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico. blancab@uabc.edu.mx