Vol. 40 (Issue 40) Year 2019. Page 17

GULIEV, Igbal 1; VOYTOV, Nikolay 2; SOKOLOVA, Elizaveta 3 & MEKHDIEV Elnur 4

Received: 01/08/2019 • Approved: 06/11/2019 • Published 18/11/2019

ABSTRACT: The authors focus on the issue of interdetermination between political events related to Russian energy projects (including Nord Stream 1 & 2) and media via examples of five European countries: Germany, Sweden, Poland, Estonia and France. The model of development of a sustainable political image influenced by mainstream media is elaborated, correlations between newsfeed in European countries are examined. Scientific novelty of the article stems from the fact that few quantitative and theoretical studies have been published on the issue. |

RESUMEN: Los autores se centran en la interdeterminación entre los eventos políticos relacionados con los proyectos energéticos rusos (Nord Stream 1 y 2) y los medios de comunicación a través de ejemplos de cinco países europeos. Se elabora el modelo de desarrollo de una imagen política sostenible influenciada por los principales medios de comunicación, se examinan las correlaciones entre las noticias en los países europeos. La novedad científica se deriva de que se han publicado pocos estudios sobre el tema. |

Contemporary Russian foreign policy sees numerous obstacles and prejudices which are coined within foreign media. Another sustainable trend is that the majority of Russian foreign undertakings, announced as well as already put into practice, perceived adversely. It is assumed that a feasible judgment of the fundamentals of existing political connotations cannot be carried out. However, according to Cohen (2015), media might not be successful in telling people what to think, but they are incredibly successful in telling their public what to think about (the so-called media object), that is to say towards the object of this study, which is represented by newsfeed of the European countries perceived as information plain in the context of which pieces of news about Russian energy projects appear. Therein, it seems viable to draw attention to the media, press and outlets and to perceive them as tastemakers of European political trends which, in their turn, in a specific way frame public consensus on certain political topics. For the purpose of this articles, quantitative analyses carried out within the study cover the time period of 2010–2017 and the informational space of the following geographic areas: Germany, Sweden, Poland, Estonia and France which are involved to the significant degree in the political process relative to the construction and operation of the Russian gas pipelines. The main objective of the study is to define the role which the European media plays in positive sense: how change politics that interact with the media? In addition, a list of recommendations relative to information support of the Russian foreign energy policy is provided.

Scientific novelty of the article stems from the fact that the thesaurus of the writings regarding the influence of the European media on Russian foreign energy policy is relatively thin. What is more, the authors seek to debunk a widespread view that the European media are intentionally biased towards Russian energy projects (instead, the media act as naturally as they could) and demonstrate that quantitative methods could be used in order to study the media as a political actor.

In a broad sense, the issue of media-politics-public interaction was studied by the following list of experts, historians and scholars.

Cohen (1986) implies that political process as it is starts with the collection of the media coverage on a certain topic. So, the foreign policy is in large part based on presumptions extracted from the media discourse. Bennett (2009) develops the idea that the media, politics and public opinion are bonded to each other, meaning that one of them cannot change its course without affecting the others. The contemporary media seeks to influence public opinion so that it would fit the media’s views on certain political topics. Culbert (1987) observes that the media reveal its political nature the more acutely the less unite is the political establishment. At the point of the apparent absence of political consensus it is the media which constitute dominant view on the political issue. Robinson (2001) infers that the media are able to produce a sporadic immense effect on foreign policy by affecting emotionally political leaders forcing them to undertake actions that contradict with the general political course. Wolfsfeld (1997) in his historical study comes to a conclusion that the international media if untamed (meaning that no restrictions are put against the right of the reporters to visit conflict regions) could be in fact exploited by the parties to the conflict by pulling in major political actors. In their article, Baum and Potter (2008) study if microeconomic postulates could be effectively adapted to the theoretical framing of the impact the media produce on both political establishment and public opinion. The so-called “CNN effect” is in fact a mere journalistic notion rather than a strong scientific concept. Hallin (1989) studies the Vietnam War case and introduces his concept of spheres (which later would acquire his name) with the help of which it is possible to classify the media discourse as a whole. Then, together with a European colleague Mancini they publish a book where the media are subdivided into groups based on its intrinsic features that stem from national traditions of a country to which they belong (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). It is found out that the European media share common traits and could be relegated to one group that is slightly different from other media (for example, the American media). Touri (2006) in her PhD thesis states that the media could be considered to be a political institution as long as they produce cognitive impact via the framing of a certain political topic that in turn affects the decisions of policymakers. Entman (2003; 2007) in his articles studies varies aspects of the media-politics relations, to name a few: the concept of media framing is elaborated that is understood as a process of filing down the news so that it would become a “product” that cloud be used by both politicians and public; if political conflict or absence of bipartisan agreement exists, the media consolidate into two antagonizing groups which seek to support one political party. The plurality of views within society and political establishment is thus reduced to two options. Norwegian scholar and scientist Galtung (1999) implies that in the 21st century it is no longer possible to perceive media as steward of policymakers as the media have transformed and evolved to be the “fourth estate” on a par with the other three conventional estates: politics, public and business.

Clearly, the list could be enlarged. There are given only milestone works according to the authors’ view.

Methods used in this work could be divided into two groups: quantitative (mediametrics) and qualitative (modeling of interactions between the media, politics and public opinion, analysis of the experts’ writings). Mediametrics as a method of analyzing the media was first introduced by Igor Nikolaychuk in his work “Political mediametrics: the foreign media and Russia’s security” (2014). Terminology associated with this method is the following (was first introduced by Nikolaychuk (2014)):

Below are given models that would be used to analyze European media discourse on the “Nord Stream” projects. In fact, as far as these models are theoretical, they could be used to study any topic reflected in the media.

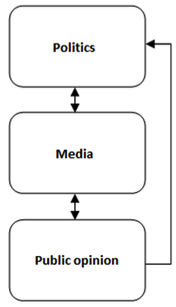

Figures 1 and 2 represent the way in which politics-media-public interaction occurs under the conditions of political consensus and its absence (based on Touri’s and Galtung’s findings).

Figure 1

Politics – media – public interaction under

the conditions of political consensus

Compiled by the authors

-----

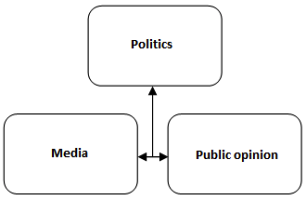

Figure 2

Politics – media – public interaction under the

conditions of the absence of political consensus

Compiled by the authors

Normally (Figure 1), media framing influences both politics and public opinion and, in turn, is influenced by them. However, politicians cannot alternate public opinion but through media framing. In contrast, public opinion has a direct leverage over the political agenda. Nevertheless, the trilateral interaction morphs into Figure 2 when the political establishment is not able to converge on a topic, then the media couple with public opinion to press policymakers directly.

Figures 1 and 2 are formalized interpretations of an alternated and particularly visualized Galtung’s model (Figure 3) (Galtung, 1999) that represents the media as the fourth estate.

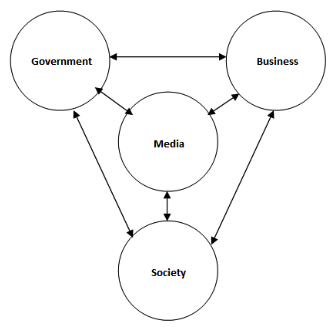

Figure 3

Galtung’s model of the media

as the fourth estate

(Galtung, 1999)

In general, the composition of the scheme infers that the professional media parties, on a par with the authorities, public and business form the constitution of the state and the social process within the national confines. Consequently, the researcher points out that the view on the media as a mere middleman of the government’s stances is in some cases outdated. This could be proven both empirically and theoretically. In a democratic state the origin of relations of power is civil society that delegates its powers to the elected authorities, so that the government could pursue a certain policy which has already been defined. In this regard, level of public support is the direct indicator of the political resource available and indirect landmark for both domestic and foreign affairs. The functions of media in this context stretch far beyond etymologically determined borders for the media acquire certain independency both from the government and public guidelines. Its’ deemed will, which is implied by the newly gained subjectivity, allows the media to pursue its own objectives and become a legitimate part of the Concept of the political (Schmitt, 2008) (understood as a rigid dichotomy, when all opinions are either ours (“friends”) or theirs (“foes”).

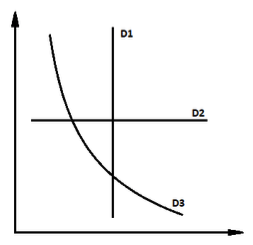

The phenomenon of the “backwards elasticity” or, broadly speaking, “elasticity of reality” (Baum and Potter, 2008), could explain to what extent the media are capable of distorting and interpreting the news for the convenience of the third parties or even themselves and give answer to the question if the media are fundamentally capable of bending the reality. The answer is positive, however, there are certain restraints, mainly the threshold after which readers revoke their trust in the media (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Graphic representation

of the Elasticity of reality

Compiled by the authors

V is the amount of information available to the public, I – is the shown interest to the news story, demand D1 are the topics of the least interest; D2, on the contrary, are the most stirring ones. D1 could be distorted to a significant degree; D2 is the epitome of impartiality and pluralism of opinions. However, these are the extreme cases, most commonly the normal elasticity of reality assumes the form of the curve D3, when the amount of the information available is in inverse ratio to the public interest (assuming that the higher is the interest, the more challenging is to manipulate the facts).

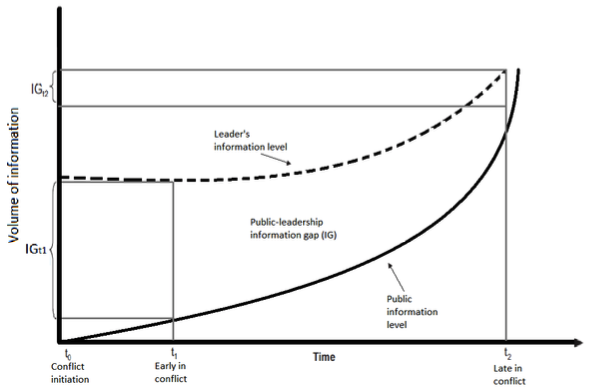

Another intriguing phenomenon from the media context is the so-called information gap model (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Baum & Potter’s model

of Information gap

(Baum and Potter, 2008)

It is about the uncontestable fact that a gap between information available to the authorities and to the public always exists. This gap narrows with time, but never attains zero. Flatness of the curve which represents the amount of information available to the public is determined by the elasticity of reality. The steeper it is, the more is the society interested in framing veracious and authentic picture of a conflict (in this case of an event from the “Nord Stream” context).

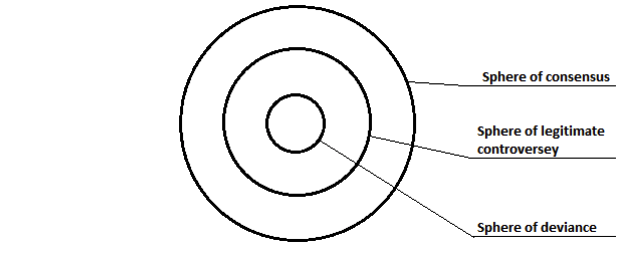

The descriptive model of the Hallin’s spheres (Figure 6) diagrammatically depicts the essence of the media discourse: sphere of consensus (axiomatics, established truths, i.e. democratic elections are good, racism is bad etc.), of legitimate controversy, (issues on which people hold different views as conflicts or foreign policy), of deviance (marginalized opinions, repugnant to morals and ethics of the society as extremist views).

Figure 6

Model of the Hallin’s spheres

(Hallin, 1989)

It could be defined mediametrically that the media mainstream is formed by the amount of the articles of the prevailing coloring, thus, the contrary colorings automatically become deviant and the space between is filled with the legitimately controversial articles. Paradigm’s shift occurs when the major coloring is being replaced in the sphere of consensus by another coloring. Fundamental political connotations and sentiments and sustainable policies burgeon in step with the development of the mainstream media discourse devoted to a certain topic and formation of the public opinion unchangeable in the middle run. That is to say, this process is relatively stable and has long running consequences.

To begin with, it is worth mentioning that within the European media subject matters attributed to Russian gas transport are the point of impact of divergent opinions. Thus, pieces of news and articles acquire a new political property, beyond common economic character. Paradigmatic cases in this context are the “Nord Stream” projects. Invoking the political terminology, European media discourse could be related to the concept of the political, as within the media context a consensus exists, which is perpetually contested by external opinions. Broadly speaking, this is the state of conflict with Russian energy projects (recurring to the journalistic language, this conflict is technically an “information warfare”). This is why a deliberate and articulate depoliticization of these projects leads instead to further tightening of links between business and politics. In such a manner, it is possible to assume that European politics and media are intertwined. However, a matter of interest in this case is whether this interaction between the media and politics is pro-cyclical or anti-cyclical. In addition, it is worth analyzing two more issues: whether is the European media discourse is natural or manually constructed and to what consequences would lead any deliberate change in the media discourse. Below are formulated three hypotheses to respond to those questions which are further tested in the study.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The media act neither pro- nor anti-cyclically (as related to the changes in politics or public opinion), but simultaneously meaning that any change in the media discourse, political agenda or/and public opinion leads to corresponding shifts in the other two domains regardless of where this change first occurred.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The European media discourse on “Nord Stream” projects is not artificially constructed.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Deliberate alternation of the media discourse cannot but worsen the overall attitude towards the topic.

Roughly, European countries which are mostly involved into the “Nord Stream” discourse could be divided into two groups: supporters and opponents of the joint venture. German government (embodied in the Ministry of foreign affairs and the current governmental coalition) supports the development of the project, as Austria. To this list France could be added. Most antagonistic opinions are expressed by the following EU counties: Sweden, Estonia and Poland. Nevertheless, studying the European news content one may arrive to a seemingly counterintuitive conclusion that there is a contradiction between the rhetoric and actions of the projects’ opponents. So, the Swedish government in the name of the ex-minister for enterprise Mikael Damberg has approved the construction of the new pipe string but stated that it still holds “critical” opinion of the project. What is more, such discrepancies, if modeled, reveal the internally consistent theoretical core (Figure 1).

The above-mentioned paradox of inconsistency between negative media coverage of the Russian pipelines and granted permissions by the European governments supported by the public opinion exists as far as the media of the EU countries do not possess property of the “backward elasticity”. It means that one the one hand the media agreeably share the government’s stance (if a firm political consensus prevails) and project its own views; on the on the other hand, the media do not see public opinion as a beacon (especially within foreign policy discourse) for its rhetoric (Figure 1). However, public opinion is the ultimate benchmark for the authorities. Nevertheless, it is necessary to adapt the generalized Galtung’s model according to the national aspects as the media (as capitalism) in each country have specific traits determined by traditions (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). That is why the German system “politics-media-public" should be modeled as follows (Figure 1). This scheme solves the presumed paradox of inconsistency between rhetoric and actions. So, in Germany public support of the “Nord Stream” projects is relatively high together with the establishment’s apparent interest in the further development of such projects as "Streams” bring both political and economic weighty benefits. In the matter, the media linger as the last opponents of the pipelines. It is possible to use the same approach in the case of Sweden, where governmental actions contradict the mainstream media discourses. That is the explanation of the presumed paradox.

It is the absence of the constant interest of readers in certain topics that allows media to benefit from the low elasticity of the public’s demand that is to coin political discourses without reference to the public opinion. However, the modest vogue of the publications related to the Nord Stream projects in the European media denote that there is a flat scope for distortions of the news which is why it is relatively complicated to manipulate the facts within this context. It is presumed that the media that hold the most hostile attitude towards Russian energy projects do not deform the facts, only limiting itself to negative coverage.

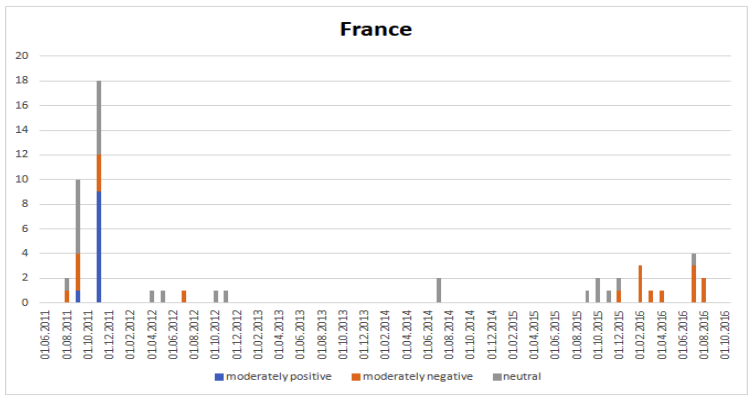

On the example of France’s media landscape, it is possible to trace the volatility of the public interest towards Russian energy projects (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Number of publications in the French media on the

“Nord Stream” projects by date and by coloring

Compiled by the authors

It should be added, though, that the average AI of France’s media discourse is 0,78 (Table A1) which means that the overall attitude towards Russian energy projects is rather soft and mild. The French press has not distorted the facts in its coverage of the topic (as far as studied publications shows), but managed to create an almost neutral image of the “Nord Stream” projects.

Consequently, it is acknowledged that the influence of the media is both constrained and determined by three parameters: discontinuity of the newsfeed (absence of the events), public opinion and political agenda. If two of the parameters are seamless and have the same vector, then the media are obliged to “move” in the same swirl (Aday, 2017). This hypothesis could be empirically tested. For instance, German public opinion is inclined to support the “Nord Stream” projects, as well as the government and the parliament. Media, as hypothesized, act in accordance with the public-politics consensus as the average Aggressiveness index does not exceed 1,05 (in contrast with Sweden (6,58) and Poland (2,28)). Nevertheless, there are certain historical conditions under which the power of the media rises exponentially, mainly dissensus of the elites (Figure 2) (Robinson, 2001). Basing on the examples of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Vietnam war, both American and European scholars have defined that the higher degree of divergency within the establishment on the foreign policy issues and the more implausible bipartisan agreement is, the more the media are able to project its own policy. That, in turn, leads to ampliation of the overall uncertainty. The supplementary factor in this case is the attitude of the media towards the policy issue. That is, the “worse” is the general attitude (measured by the coloring), the more actively the media seek to influence the policy. In this context, the society preserves its function as the ultimate arbiter, as both the establishment and the media address to its opinion on the issue aspiring to form the resultant advantageous stance for themselves. Amidst conflict it is obvious that the government and the professional media participants are the direct competitors for the public opinion to each other. So to say, it is possible to conclude that as long as in the Germany’s government consensus on the “Nord Stream” projects persists, public opinion is not to be modified, as the media despite the overall moderately skeptical tone are obliged to follow the mainstream trend of public-government sentiment as the model of the lasting elite consensus presupposes. If adjusted for the democratic state (Figure 1) this model anticipates that the establishment does not possess direct means of influence on the society and mediates its views through the media which, in turn, are able to react to the government’s actions, revealing its own agency. However, it is possible to model an alternative approach to the interaction between politics, media and public opinion, taking into consideration the above-mentioned factors of instability (Figure 2). Ambitendency of the newly constructed mechanism of politics-media-public interaction (Wolfsfield, 1997) could be described as follows: contradistinction of the two layers (politics against the alliance of the media and public opinion with the media possessing leadership) and disengaging the recursiveness (the flow of ideas and opinions no longer circulate from the government to the society through the media and back again). Consequently, the media being the object of this interaction triangle (not the subject) gain new traits of an actor. Thus, the role of public opinion is crucial to the Concept of the political.

On the example of the customized model of the monopolistic competition, as applicable to the media, attempts to deliberately influence the discourses relevant to Russian foreign energy policy are proved to be futile (testing of the H3). However, the application of this model leaves the question to what extent the current image of Russian foreign policy in the European media is intrinsic without a direct answer. Nevertheless, using the indirect evidence, including the above-mentioned modeling, it becomes plausible to conclude that the media mainstream is formed arbitrarily rather than artificially. In order to conduct a deeper structural analysis of the processes that take place within the media that occur regardless of the surrounding constitution of the prevailing socio-political conditions, it is necessary to address to the Hallin’s spheres concept (Figure 6), adding its’ elements to the below-built customized model of the monopolistic competition.

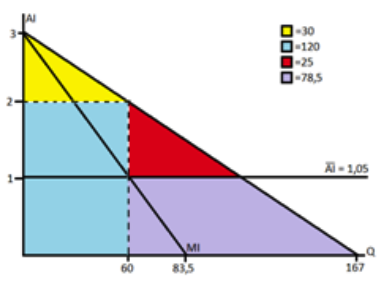

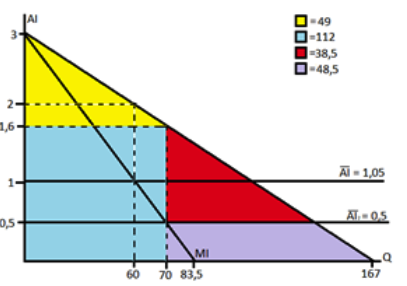

The experts studying the interaction between the media and politics, point to the fact that they relate to each other in market terms (Baum and Potter 2008) and thus follow the laws of the free market (namely laws of demand and supply) that tend to define the stable ratio between the production and consumption of information. As mediametrics enjoy quantitative nature and could be modeled, a simulation of the media supply-demand mechanism is developed for Germany. In this case the sectorial demand is the amount of publications on the “Nord Steam” projects. In this manner, the classical monopoly (Figure 8) is the triangle-shaped area that integrates the aggregated demand for the content of a certain kind (news, articles etc.).

Figure 8

Analytical representation of the German media

discourse on the “Nord Stream” projects

Compiled by the authors

Similarly, a media topic could be measured in terms of quantity (Q), intensity (Aggressiveness index – AI, an alternative to the price, P). The average AI replaces the curve of marginal costs (modeled linearly as it is presupposed that the cost of each consecutive publication is a constant). Marginal impact line (MI) serves as equivalent to the marginal income function and marks the threshold impact that could be attained via influencing the public opinion on the chosen topic. The length of the axis Q is 167 (the total number of the publications on the issue of “Nord Streams” in Germany), that of the Ai axis – 3, which is the maximum value of the AI for the topic (it is supposed that higher indicators are unavailable under the current political trends).

The space marked with blue is the Hallin’s sphere of consensus (mainstream media discourse), with yellow – sphere of legitimate controversy, with red – sphere of deviance. Along the lines of the monopolistic competition, consumer surplus (yellow triangle) is the area where readers are free to form their own opinion on the topic, dead loss (red) is the sphere of deviance, i.e. a chain of opinions which are opposed to the mainstream discourse on the topic. Commonly, the read area is literally perceived as a dead loss, however, this notion is not fully adequate as Chamberlin, one of the founders of the monopolistic competition theory, found out that the “loss” is in fact the price which the society pays for the variability of the goods available (in the case of the media, for the publications of different colorings). The violet figure is the uncovered layer of readers which are not interested in the topic due to its tenseness (measured by the AI). It could be derived that in Germany today a sustainable public consensus exists that is two times more saturated than the other two spheres.

Despite the fact that the general AI level in Germany in regard to “Nord Stream” topic is relatively moderate, a scenario when public opinion is alternated artificially should be tested in order to prove the futility of such attempts. The above-given model is used to evaluate the results of instantaneous sharp decline in the average AI (an imaginary situation in which all publications of negative colorings were replaced with the more neutral ones so that the average AI would decrease to 0,5). As a result of these transformations (Figure 9), the sphere of consensus would shrink while the other two spheres would accrue.

Figure 9

Analytical representation of the German media discourse on the

“Nord Stream” projects when the average AI is artificially lowered

Compiled by the authors

However, the prevailing discourse would not be challenged; in addition to that, a larger target audience (colored with purple) would reveal its interest in the topic which would inevitably lead to the enlargement of the media discourse. As a result, public support in Germany for Russian energy projects would dwindle. As far as the public-media-policy interaction in Germany is recursive, a decline in governmental support is expected as well.

It could be easily found out that the identical outcome would emerge if the model is scaled. This leads to a conclusion that there are not any silver bullets with the help of which the media context could be modified swiftly. Instead, this process should be carried out cautiously and consequently. Analogous modeling for Sweden, Estonia and Poland would have the same proportions with the only difference is that the sphere of consensus would be broader and the scaling of model or the lowering of the average AI would lead to a more drastic decline in public support of Russian energy projects.

Normally, for a country with elaborated and dynamic domestic politics foreign policy issues are of a secondary importance. This suggests that public opinion which is formed by refracted publications in the media does not demonstrate considerate interest to Russian energy projects (compared to domestic issues), while the media do not issue much publications on that topic (Frizis, 2013), which indirectly supports hypothesis about the uncoined nature of “Nord Stream” portrayal in the media. However, plausible errors of attribution that intrinsically exists within the Russian media could create a distorted impression (in Russia) that there is a constant inimical attitude in the European media towards Russian energy projects. To verify this hypothesis an analysis of the most established media, namely European think tanks, is needed. It is supposed that its deliveries could be seen as an aggregated expertise that flows as core theses into the sphere of consensus and as recommendations into the government.

European institutions, as expected, have diverse opinions on the Russian foreign energy policy. What is more, it seems counterintuitive, though many European think tanks intentionally avoid discussing the topic of “Nord Streams” (for example, Chatham House, Danish institute for international studies and Konrad Adenauer Foundation). Others, as, for example, the European branch of Carnegie Endowment in a publication which synthesizes opinions of European experts on the topic of the Russian pipelines, provide a relatively disadvantageous picture – for Russia (Dempsey, 2018). The only expert from the above-mentioned publication who seems to disagree with the mainstream discourse, is Angela Stent who, in fact, supports the construction of new pipelines from Russia to Europe (as it lies within the area of interest of all parties concerned). The rest of the experts unanimously supports the halt of “Nord Stream-2". Their argumentation could be reduced to two core theses: Ukraine and dependency on Russian hydrocarbons. IFRI, as the most established European think tank (McGann, 2017), on the contrary states that it is Russia itself which is the most dependent on gas supplies, and mentions the fact that the EU itself is a growing net importer of energy resources and that the domestic production of hydrocarbons is in decline (Aoun, 2016). As a result, a sustainable and cheap logistic structure is needed. According to IFRI’s expert opinion, “Nord Stream” project will satisfy this demand. Another respected European think tank, Bruegel, shares Carnegie’s stance on the issue (it is worth mentioning that in Bruegel there is only one expert that provides expertise on the topic): the project should be abandoned as it threatens Ukrainian security. In such a manner, it could be concluded that low popularity of news stories related to the Russian foreign energy policy found in the media completely corresponds with its avoidance within the European think tanks expertise.

The impact of media discourse on Russia-EU relations could be traced by country though the role of media discourse for each studied country varies. For Germany, its media discourse plays a role of a domestic safeguard against the external pressure: it is supposed that its NATO (mainly the USA) and EU allies have demurs against Germany further tightening energy links with Russia. The US as a major oil and gas exporter is interested in gaining access to new and large markets. The problem is that such markets are already filled up with by existing exporters: Russian gas routs to Europe have been operating for decades with the prices being slightly below the market. Nevertheless, European demand for gas in on the rise and Russia tries to respond to this challenge by constructing new branches of the existing pipelines. Accrescent European gas market is an attractive destination for the US liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers, so the US authorities are striving to reserve a niche for future deliveries which could found out to be empty once “Nord Stream 2” is put into operation. Still, German government does not cede to the US demands for various reasons, to name a few: the need to construct LNG infrastructure, higher LNG prices (compared with the Russian gas). However, it is worth mentioning, as discussed above, that the German media and public opinion have a neutral attitude towards the projects, so to change it the German government needs to bear significant political costs (Figure 9). So, a status quo is preserved and the “Nord Stream” project is supported. In France’s case, it is observable that no significant interest is devoted to the topic. This is explainable as far as France’s and Russia’s energy policies have few intersections and do not compete with each other. That is why the French media discourse on the topic is rather constrained and anemic. Low average AI reflects France’s demonstrative detachment from the topic as it is. In Estonia, neither the media nor public opinion does speak out against the construction of the “Nord Stream”. This could serve as a rationale to explain why Estonian establishment which supports the halt of the construction is not able to produce any deliverables in this context. Russian-Polish relations have been rather strained and not easy. In the “Nord Stream” case it is noticeable that a high average AI coincides with both negative political rhetoric and public opinion. Sweden, as was discussed above, is a splendid example of how the media discourse could be constrained and rendered innocuous by moderately neutral public opinion and permissive governmental actions. If summarized, the results are as follows: congruent media coverage and public opinion deprives the government of the right to act contrary to the media-public consensus; public-government alliance neutralizes excessively vehement (of the contrasting coloring) media coverage. However, it has not been found out what happens when the politics-media tandem contradicts public opinion as the authors did not manage to find any data that would depict such a situation.

The three hypotheses have been tested on empirical findings with the following outcomes. H1 states that the any change in the media discourse (either coloring of the sphere of consensus or its size) may not happen singularly, as it is always accompanied by the proportionate changes in the public opinion or political agenda. As during the studied period, the countries’ stances on the “Nord Stream” projects have stayed the same (so has public opinion, according to the data available), the media coverage also has not undergone major changes. From the data given in the appendix (Figures A1–A5, Table A1), it could be seen that dashes of the number of publications are a mere reaction to the particular piece of news (for example, a stipulation of the memorandum of understanding between Russia and a European country on the construction of a pipeline) and their AI remains on the same level. Still, it is an apagogic proof of the H1, so it could be challenged by further studies in this field.

H2, which states that the European media discourse is a natural rather than a constructed phenomenon, is sustained by two circumstances. First, there has not been observed any significant discrepancies or distortions of facts in the publications studied; second, the media discourse of a chosen country has a deducible coloring (from the built theoretical frames).

What is more, the proposed theoretical frames are found to be suitable for analyzing European media discourse with minor adjustments. This may serve as an evidence of the fact that the models articulated by the above-mentioned historians, journalists and scholars are well-grounded and still up-to-date. Customized monopolistic competition model (proposed by the authors) adopted to the needs of mediametrics as elaborated above allowed to produce a well-grounded evidence for the H3 which states that there is no way in which the media discourse could be alternated swiftly to the advantage of the actor who (or which) seeks to change it. This finding renders quasi impossible any judgments according to which the media “complot” against certain actors or topics.

Further studies could cover the unanswered questions that have arisen during the research: is the topic of Russian foreign policy (energy policy) indigenous to the European media discourse (or extraneous); is a situation of the struggle between media-politics and public opinion is plausible. The answer to the former would allow to define to what extent topics associated with Russia could be interpreted and bended (according to the elasticity of reality theory); to the latter would allow to build a complete theoretical frame of the possible combinations of trilateral relations between the media, politics and public opinion.

Aday, S. (2017). The US Media, Foreign Policy, and Public Support for War. In K. Kenski and K. Hall Jamieson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication (pp. 315–332). NY: Oxford University Press.

Aoun, M.-C. (2016). Nord Stream 2: May Cooler Heads Prevail. Paris: Institut français des relations internationales (IFRI).

Baum, M. A., and Potter P. B. K. (2008). The relationships between mass media, public opinion, and foreign policy: Toward a theoretical synthesis. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci., 11, 39–65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060406.214132

Bennett, W. L. (1990). Toward a theory of press‐state relations in the United States. Journal of communication, 40, 103–127. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02265.x.

Cohen, B.C. (2015). Political Process and Foreign Policy. The Making of the Japanese Peace. Princeton: Princeton University Press. First published 1957. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400878536.

Cohen, Y. (1986). Media Diplomacy: The Foreign Office in the Mass Communications Age. Abingdon: Frank Cass.

Culbert, D. (1987). Johnson and the Media. In R. A. Divine (Ed.), The Johnson Years, Volume One: Foreign Policy, the Great Society and the White House (pp. 224–227). Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Dempsey, J. (2018). Judy Asks: Should Germany Dump Nord Stream 2? Can it? Carnegie Europe. Retrieved from: https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/76597

Entman, R. M. (2003). Cascading activation: Contesting the White House's frame after 9/11. Political Communication, 20, 415–432. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600390244176.

Entman, R. M. (2007). Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of communication, 57, 163–73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x.

Frizis, I. (2013). The Impact of Media on Foreign Policy. Retrieved from: https://www.e-ir.info/2013/05/10/the-impact-of-media-on-foreign-policy/

Galtung, J. (1999). State, capital, and the civil society: The problem of communication. In R. C. Vincent, K. Nordenstreng, and M. Traber (Eds.), Towards equity in global communication: MacBride update (pp. 3–21). Cresskill: Hampton Press.

Hallin, D. C. (1989). The uncensored war: The media and Vietnam. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hallin, D. C., and Mancini P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge university press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790867

McGann, J. G. (2017). 2017 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report. Retrieved from: https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=think_tanks

Nikolaychuk, I. (2014). Political mediametrics: Foreign media and Russia’s security. Moscow: RISS.

Nord Stream 2. (2018). Forsa: Opinion poll shows clear majority in support of Nord Stream 2 and natural gas in Germany. Retrieved from: https://www.nord-stream2.com/media-info/commentary-analysis/opinion-poll-shows-clear-majority-in-support-of-nord-stream-2-and-natural-gas-in-germany-24/

Robinson, P. (2001). Theorizing the influence of media on world politics: Models of media influence on foreign policy. European Journal of Communication, 16, 523–544. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323101016004005.

Schmitt, C. (2008). The concept of the political: Expanded edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Touri, M. (2006). Media-government interactions and foreign policy: a rational choice approach to the media's impact on political decision-making and the paradigm of the Greek-Turkish conflict. (PhD. Thesis). University of Leeds. Leeds, the UK.

Wolfsfeld,G. (1997). Media and Political Conflict: News from the Middle East. New York: Cambridge University Press.

1. PhD, associate professor, deputy director of International Institute of Energy Policy and Diplomacy, MGIMO University, Moscow, Russia

2. Researcher at Energy and Digital Economy Strategic Research Center, MGIMO University, Moscow, Russia

3. Doctor of Economics, Professor, Director of the Center for Analysis, Risk Management and Internal Control in Digital Space, Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia

4. PhD, Leading researcher, Center for Analysis, Risk Management and Internal Control in Digital Space, Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia. Contact e-mail: e.mehdiev@gmail.com