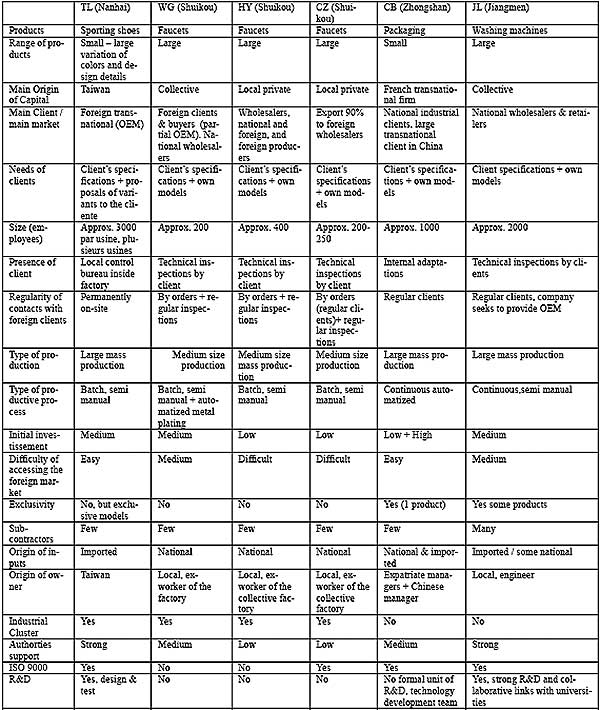

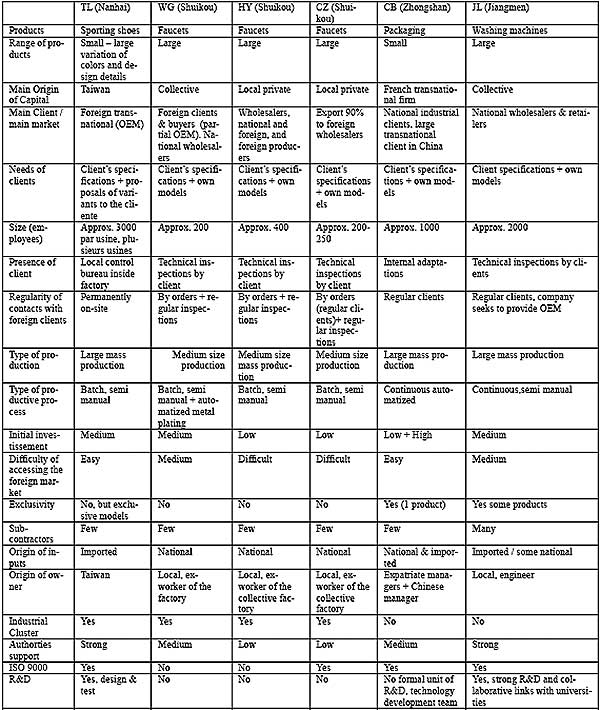

Table 3.

Analysis of Six exemples of relations of Chinese entreprises with foreign clients

Rigas Arvanitis y Zhao Wei

We chose six very diverse case-studies in order to highlight the relations of the companies with their foreign clients. Table 3 shows a summary of the characteristics of the companies, and Table 4 summarizes the four models of learning that we could identify through these cases. Learning can be very different, but a large part comes from the support the client gives to the company as it inspects its processes, gives the blueprints and pushes the provider to give them high quality. Here the client is the provider of technology and the providers of products are the users of the technology: the userprovider relation is inverse from that one would understand by the expression “userprovider”.

Table 3.

Analysis of Six exemples of relations of Chinese entreprises with foreign clients

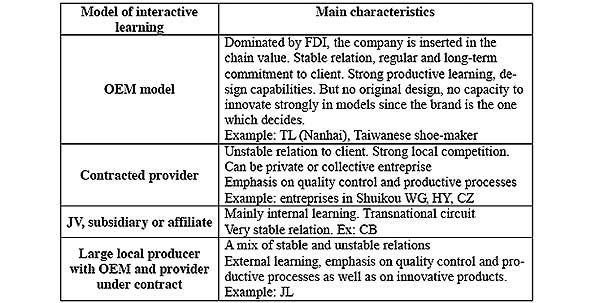

The large diversity of cases can be reduced to some types of the cases that are shown by the theory. Without taking into account internal learning, we could figure out four different types of learning (table 4).

Table 4

A brief typology of models of interactive learning.

1. The OEM model. The first, the OEM model, is what made Taiwan famous. Particularly well fit for a globalized industry, the international brand is the one giving productive orders. The local factory deals with the local advantages and exploits the low cost of labour as well as its high quality control. R&D is not done unless its serves the purposes of the brand. The brand company is the one making higher margins and exploiting its decisive advantage: access to market. But the decisive access has ne mean if low cost is not maintained by the local producer. Taiwan producers, after 1990, understood the full advantage they could get from coming to mainland China (Guiheux 2000b). Hong Kong capitalists have also come to Mainland China for the same reason, transforming Hong Kong in an industrial desert. Local Chinese entreprises do not catch foreign clients with the same facility.

2. Contracted provider. The second case is very well illustrated by the Shuikou industrial cluster (Sun and Xu 2001). It is of interest because it is a medium range solution for those companies that look for very cheap providers, like is the case of faucets industry. Again, for the same reason, difficult access to the international market obliges to accept the conditions imposed by the foreign client. In fact, the local companies do this very gladly. They are aching at having foreign clients. “Our clients as our teacher” said one manager in this city we visited. All the quality producer are linked one way or another to international clients and it is through this contact that they could get access to higher quality models and to improvements in quality. It is also because they can get better prices in the international market that they get better incomes and can afford full access to ISO certifications. Companies become contracted providers for foreign clients because they have to. The local market will be unable to accept such a large quantity of producers and ssoner or later the best ones will survive a market become more and more competitive. In this competition it is not only companies which compete. Regions also are competing to keep the companies. Even in one municipality, smaller and newer companies are very much tempted to go to next door administrative region because the price of land is lower. Companies are also competing for the favors of the local government, not the economic ones, but mainly the easier access to foreign clients which can be seriously affected by the local authorities (visas, authorizations, imports, exports). Local authorities never fund directly of indirectly a business. What they have been doing is working on the image of the city, providing all the necessary support in the construction of a commercial fair, promoting and publicizing the city outside the region and the city. Probably some more direct relations exist between the financial office and very specific companies but these are not a policy, but rather personal relations which in some cases are promoted by the local government officials (with great care, since corruption is very heavily punished). Even the label of “industrial cluster” is a posteriori, not a policy itself but rather a qualification of the economic space. There has not been –to our knowledge— a specific policy in promoting the entreprises any different from this laisser faire like in the rest of the Guangdong region.

3. The JV model. JVs were once thought to be the panacea. They were supposed to bring money and technology to Asia, mainly China and Vietnam. Vietnam today is experiencing a considerable fall in the investments and China has provided legislative effort in order to promote FDI in different forms from JVs. Foreigners are usually uncomfortable with the figure of the JV and most foreign companies now want to become Wholly owned foreign entreprises, since the law is authorizing this new possibility. The partnership is a forced one, not a chosen one, and whatever the benefits, it is always be seen with suspicion. Inside the figure of JV there are great variations. Technologies flow usually well and there is an important flow of know-how, as would be the case of the subsidiary of a transnational firm. But in no case, have we seen an effort that will be genuinely local and independent form the “mother”-house. All decisions in fine depend on the internal structure of the transnational or the foreign partner.

4. The mixed model. This would look as the ideal model, wouldn’t it be for its long time. JL, our example, is a rarely met example in China. Other large companies in China, like Haier, TCL, Konka, Legend or Fenghua would be similar in many aspects; but these companies are not so numerous. The company has a learning strategy, mainly based on technological development and high standard in production. It is not trying to cut costs at the expenses of investment. It develops collaborative R&D with outside sources of knowledge. Nonetheless, one of its objectives, an objective not so clearly stated is to become, at least partially, an OEM provider. This would allow for lower cost in entering the foreign markets. At the same time the company seeks to get a grip on the technology as well as the marketing in foreign countries. One of the ways it will try to do that is by setting up facilities in the foreign country.

It appears to us that the miracle of South China industrialization is based on a specific economic phenomenon: the creation of entreprises in a place where nothing existed before, and where close collaboration with foreign partners was made easy. Guangdong’s development has relied on basically unskilled labour in productive units funded by foreign capitals. Local entrepreneurs have appeared and try to enter this same logic. Today, they are faced with a different choice: that of upgrading the technology of the already existing entreprises. The very low labour cost does not provide sufficient incentive for firms to invest heavily. The limit of a good manual production in terms of quality can be attained quite quickly. In some sectors like pharmaceutics, electronics, consumer electronics, computers, this limit needs to breaken and entreprises need to switch to automatized and semi-automatized productive processes. The difference between the successful and unsuccessful industrial companies is their ability to enter and maintain close relations with a foreign partner. For a small company this means a foreign client. Up to a certain point, the stability of this relation will depend on internal learning and strategic capability of the company. If Guangdong, and China in general will be able to manage the large array of competing learning models is still open to question. But there is no sign either to be overly pessimistic, nor extremely optimistic.

The survival of companies that do not upgrade is also dependent on the internal competition. Today, for example, the Guangdong province, which was one step ahead, is becoming expensive, as compared to other regions on the coast or the hinterland. Competition between regions is going to grow in order to attract newly arrived FDI. The model followed until know, is thus arriving at its limits. Even growth in size in is problematic, because of scarce access to funding, but necessary, if companies want to maintain their technological abilities high. The upgrading is thus the neuralgic point which will decide the death or survival of an entreprise.

Most locally founded companies have had access to better technology by having foreign clients. This provides the incentive that labour cost do not provide. Moreover it opens possibilities of wider production, wider knowledge, wider markets. Association with a foreign client is thus strategic to practically all companies that want to go up the value chain, to approach the technological frontier and to access the more lucrative markets.

Up to now the situation is no doubt that of technological dependence from foreign sources. The national system of innovation although showing impressive figures is still a rhetoric rather a reality and cannot provide productive technologies in the quantities and of the types needed for production. Collaborations with scientific institutions from the productive sector are still rare, and when that happens it seems easier for public owned companies (Legend was a research center, “999” a famous pharmaceutical entreprise was a hospital laboratory belonging to the army). In our case, it is JL, the collective company belonging to the city of Jiangmen that has extensive links with universities and research centers as far as Beijing and Harbin (Jiangmen-Harbin is far 3.000 kms).