Vol. 40 (Number 35) Year 2019. Page 3

CASTILLO-VILLAR, Fernando R. 1 & CAVAZOS-ARROYO, Judith 2

Received: 26/06/2019 • Approved: 05/10/2019 • Published 14/10/2019

ABSTRACT: The scaling of social impact has become an important issue in the field of social entrepreneurship. However, little attention has been given to two inquiry pathways: scalability in developing countries and the role of supply chain management in scaling social impact. Hence, the main objective of this article is aimed to identify the challenges social entrepreneurs face when managing their supply chains in order to scale up social impact. |

RESUMEN: El escalamiento del impacto social se ha convertido en un tema importante del emprendimiento social. Sin embargo, poca atención se ha prestado a dos vías de investigación: la escalabilidad en países en desarrollo y la gestión de la cadena de suministro en este proceso. Por lo tanto, el principal objetivo de este artículo es identificar los retos que los emprendedores sociales enfrentan durante la gestión de la cadena de suministro con el fin de escalar su impacto social. |

Over the last decade, social entrepreneurs have become key actors to address social and environmental problems (Blundel & Lyon, 2015; Koniagina et al. 2019; Smith, Kistruck & Cannatelli, 2016). The overarching goal of social entrepreneurs is the provision of solutions of high social impact in order to generate value to society (El Ebrashi,2018). However, one of the most challenging tasks for social entrepreneurs is to scale the social impact of their activities (Scheuerle and Schmitz, 2016). In most of the cases, social entrepreneurs are only able to solve social problems at a local level due to both internal and external constraints (Zajko and Hojnik, 2018).

Scaling social impact is an important topic in social entrepreneurship literature (Cannatelli, 2017) but more research is still needed regarding processes and knowledge social enterprises can apply to achieve this goal (Gauthier et al. 2018). Specifically, it is necessary to develop studies focused on understanding social impact scalability in developing countries where the lack of institutional and market infrastructure limits, even more, the capacity of social enterprises (Desa and Koch, 2014). Under these contexts, social enterprises must develop innovative solutions based on limited resources (Bocken et al. 2016).

Due to the vastness of strategies and drivers that influence the scalability of social enterprises, the current research will focus on analysing one specific element: supply chain. This element is essential to influence the scalability of social impact in social enterprises (Walske and Tyson, 2015). Yet, the management of a supply chain is challenging for social enterprises operating in developing countries due to diverse limitations such as greater transaction costs and weak regulatory systems (Tate and Bals, 2018). Therefore, the main goal of the research is to analyse how social enterprises deal with the challenge of managing their supply chains in order to scale social impact.

The article is structured as follows. First, a systematic review on scaling social impact in social enterprises is provided, along with arguments supporting the need for addressing this phenomenon in emerging countries and from a supply chain perspective. Afterwards, a brief explanation of the logic underlying the selection of Mexican social enterprises to carry out interviews is presented as part of the methodology section. Finally, the main findings of the interviews, contributions and future research areas are discussed.

Social enterprises have gained great recognition as alternatives to tackle contemporary social and environmental problems that have not been effectively addressed by governments (Blundel and Lyon, 2015). According to Zajko and Hojnik (2018), social enterprises are “… social, mission-driven organizations that develop an entrepreneurial activity in order to fulfil unsolved social needs in society” (p. 1). In this case, a social enterprise may be conceived as an attempt to combine the social mission of NGOs with the effectiveness and economic sustainability of business organizations (Ingstad et al. 2014).

However, a challenging task for social entrepreneurs lies on their ability to scale their social enterprises (Smith et al. 2016; Renko, 2013; Lyon and Fernandez, 2012; Bloom and Smith, 2010). This problem cannot be treated from the same theoretical approach of scaling used in management and entrepreneurship domains since the phenomenon of scaling in social enterprises comprises unique characteristics associated with solving public problems (Smith and Stevenson, 2010; Weber et al. 2012). Most of the time, social entrepreneurs face diverse constraints regarding the complexity of dealing with paradoxical situations caused by pursuing both economic and social objectives (Ingstad et al. 2014).

Blundel and Lyon (2015) stress the relevance of paying attention to the logic duality (commercial and social) adopted by social enterprises. The authors contend that the measurement and analysis of scalability in social enterprises turn problematic as revenue, which is considered an important metric to measure growth in businesses; cannot be the primary indicator to determine the success of a social enterprise in terms of scalability. Likewise, the scalability of social enterprises cannot be reduced to the final goal of growing in terms of size (expansion of the enterprise) or number (increment in customers or members of the organization) (Bocken et al. 2016).

Therefore, the current research draws on CASE’s definition of scaling (2006) as the process of “… increasing the impact a social-purpose organization has on the communities it serves or the social needs it addresses” (p. 3). This definition expands the idea of scaling beyond just growing larger (Blundel and Lyon, 2015) and puts forth the relevance of increasing social impact by creating social value (Desa and Koch, 2014). Thus, scaling social impact has become an important research topic in the field of social entrepreneurship (Smith et al. 2016).

Scaling social impact may be regarded as an emergent phenomenon in social entrepreneurship domain and hence it is necessary to gain more insights about it (Smith et al. 2016). A promising area of interest worth to explore is the scalability of social enterprises in developing countries. Even though environmental and social issues exist in both developed and developing countries, there are prominent differences regarding their extent and nature (Rivera-Santos et al. 2015). In developing countries, poverty is larger in proportion (compared to developed countries) and poor people are the most affected by threats such as climate change, political instability and economic crisis (Bocken et al. 2016).

Consequently, social enterprises have been essential to address social and environmental problems in developing countries (Desa and Koch, 2014). Yet, there are plenty of limitations that affect directly the performance and effectiveness of social enterprises in these contexts, such as lack of infrastructure, institutional constraints and market failures (Desa and Koch, 2014). In addition, social enterprises must operate with limited resources since policies aimed to support entrepreneurs in developing countries are commonly inefficient, if not inexistent (Bacq et al. 2015). All of this negatively influences the ability of social enterprises to scale social impact and efficiently meet the demands of the target population.

Desa and Koch (2014) distinguish three types of market failures in developing markets that affect the scalability of social enterprises: supply-side resources constraints, demanding-side adoption problems and distribution channel/infrastructure issues. Based on these constraints, social enterprises must develop organizational capabilities to operate effectively in developing countries. The current research will focus specifically on how social enterprises cope with the last market failure: Distribution channel/infrastructure. The distribution of products is relevant for social enterprises to increase market penetration, economic viability and social impact (Bocken et al. 2016). On the other hand, the lack of distribution channels is one of the main barriers that interfere with the scalability of social enterprises (Weber et al. 2012).

Supply chain may be defined as the flow of the distribution channel from the supplier to the final user (Ellram and Cooper, 2014). The main purpose of the supply chain lies in the acquisition, production and distribution of products and services demanded by customers. Currently, the business environment requires strong operational integration among the members of the supply chain to develop, produce and deliver the goods at low cost and high quality. Thus, supply chain comprises a network of businesses relationships that produce value (Sohdi and Tang, 2014).

Supply chains are central for social enterprises to scaling social impact (Walske and Tyson, 2015). However, the development of supply chains in developing countries is hindered by several limitations such as weak regulatory systems, the absence of intermediaries and greater transaction costs (Tate and Bals, 2018). In contrast with developed countries, social enterprises operating in developing countries must build supply chains from scratch due to inadequate distribution infrastructure and channels to reach the target population (Sodhi and Tang, 2016). Hence, social enterprises must design innovative ways to develop supply chains under these contexts in order to offer economically viable and effective product use (Desa and Koch, 2014).

A feasible strategy that social enterprises may apply to develop supply chains is the formation of partnerships and collaborative relationships with suppliers, intermediaries and distributors. Based on a comparative analysis of growth strategies used by 10 social enterprises in Egypt, El Ebrashi (2018) identified value chain partnerships as an effective vertical growth strategy to enhance product distribution and facilitate access to customer or beneficiaries. This is in line with the observation of Newbert(2012) on the importance of building relationships with supply chain partners to improve scalability of social enterprises.

The main interest of the current research is to understand how social enterprises cope with the task of building up effective supply chains in developing countries. The importance of supply chains to aid social enterprises to scale their social impact has been recognized recently and hence, further research is needed to shed light on the nuances and complexities of this process (Walske and Tyson, 2015). However, a broad analysis to supply chains must encompass not just partnerships within the physical supply chain, but also in the support supply chain. Carter et al. (2015) emphasize that the physical supply chain must be supported by both information and financial supply chains. Therefore, this approach will be used to address the central research question.

A qualitative research approach based on in-depth interviews was applied to the study of 12 Mexican social enterprises as the main aim of this article is to understand how the leaders of these organizations deal with the management of their supply chains in order to scale their social impact. Regarding the research context, Mexico has been recently considered as a promising emerging economy and one of the “pivotal states” in the developing world (Gonzalez, 2014). Moreover, a genuine entrepreneurial spirit has bloomed in Mexico, where diverse social enterprises have developed innovative ways to solve social challenges within a context with high levels of inequality and governmental corruption (Perusquia and Ramírez, 2019; Wulleman and Hudon, 2016).

Nevertheless, the Mexican context also presents great social and political problems. In Mexico, more than half of the population lives in poverty without access to fundamental services due to the limited capacity of the government for developing effective social policies (Cavazos-Arroyo et al. 2017). In addition, high levels of corruption in Mexico negatively affect the trust of social entrepreneurs and citizens towards the government and its institutions (Wulleman and Hudon, 2016). Hence, most of the Mexican social enterprises have to operate within a hostile environment that does not contribute to facilitate their task of scaling up social impact.

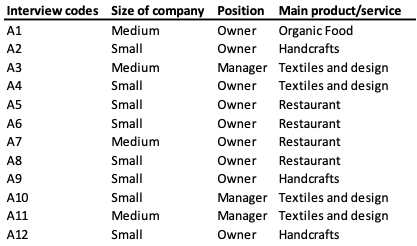

For each social enterprise, an in-depth interview was held with the director or general manager (Table 1). The selection of social enterprises included seeking a variety of business goals with the aim of documenting similarities and variations within their supply chain management and thus, to identify common patterns (Marshall and Rossman, 1999). The sample was selected considering the following characteristics:

The selection of social enterprises was based on the following criteria:

• Companies denominated as social enterprises by the National Institute of Entrepreneurs (INADEM);

• Small and medium social enterprises with at least 3 years of operations.

• Access to key actors responsible for the management of the supply chain.

Table 1

List of managers and owners of small

and medium Mexican social enterprises

The interviews were carried out between January and April 2019. The interview structure was divided into four main topics: Relationship with supply chain stakeholders, physical supply chain operations, financial supply chain and, type of information shared by supply chain stakeholders. The results of in-depth interviews were complemented with secondary sources of social enterprises (reports and websites). The interviews were recorded and transcribed in order to analyse the data through an iterative analytical process. This process facilitates the identification of differences and similarities across the main topics addressed by the interviewees. Triangulation of data was developed through the revision of data interpretation by two external researchers.

Based on the interviews, it was clear to identify a strong conviction from social entrepreneurs for holding strong relationships with their main suppliers. Interviewees point out that one of the most important objectives of their social enterprises is to maximize the social impact through helping their suppliers to improve their living conditions. In the case of the Mexican context, there is a strong tradition of social enterprises to work with suppliers from rural and indigenous communities (Wulleman and Hudon, 2016). These marginalized communities are commonly ignored by federal and regional governments, so that social entrepreneurs see this failure in the system as an opportunity to alleviate a relevant social demand.

“Our main suppliers are from a community nearby El Paso de Cortés (San Mateo). It is a community that preserves its language and its roots … (This) is a small restaurant whose characteristic is that its employees come from the United States… in addition, its suppliers focus on the production of corn. Our suppliers sell the products they harvest and, at the same time, we help neighbouring communities by purchasing their products” (A5, Owner of a small restaurant).

Nevertheless, social entrepreneurs have also faced difficulties concerning the incorporation of new information and processes to the development and design of supply chains. In resource-constrained contexts, Desa and Koch (2014) recommend that social entrepreneurs must draw on collaborative processes and iterative learning in order to convince rural stakeholders to change their supply chain mechanisms. Yet, interviewees’ responses reveal that the process of educating supply chain stakeholders is time-consuming and expensive thereby social entrepreneurs prefer to scaling social impact through other means (e.g communication strategies and product/service innovation).

“Educating suppliers is a difficult process... especially, in terms of deliveries ... they cannot bring product in plastic bags, only in tares… Sometimes it was also necessary to return the product until they understood how they should deliver it. It has been very difficult because you compete with a culture, with an idea that is already established and deeply rooted for a long time” (A8, Owner of a small restaurant).

The physical supply chain refers to the system of agents that facilitates the movement of a product from the supplier to the final customer (Carter et al. 2015). As aforementioned before, most of the interviewed Mexican social entrepreneurs collaborate with suppliers from rural and indigenous communities. However, this dynamic in turn generates specific barriers that limit the capacity of social enterprises to develop a more effective supply chain. One of them is the lack of transport infrastructure. Rural communities in Mexico are poorly connected via road networks with the major urban areas. Hence, the delivery of products can turn into a big challenge to overcome for social enterprises since they need to keep operating under constraints of time and quantity of product.

"They do not have transportation. They do everything by public transport. Trying to deliver 4-5 boxes is a problem for them, it's a challenge… They always arrive by bus... they bring things in boxes or in backpacks” (A7, Owner of a medium-sized restaurant).

In addition, rural suppliers have a limited capacity of production due to lack of raw material and quality control in their processes and activities. These limitations directly affect the performance of social enterprises as they find difficult to both anticipate supply shortages and meet the variations of the demand. Thus, this condition generates a vicious cycle in which rural suppliers cannot maintain consistency in the delivery of products, distributors face difficulties to get to rural areas due to the lack of transport infrastructure, and social enterprises are hampered to achieve scalability. In this case, social entrepreneurs should opt to either reduce the supply chain in order to gain control in most of the processes of production/delivery or invest in capacitation and equipment for suppliers in order to optimize the supply chain.

“The artisans cannot produce what we request. We need to evaluate the right quality, price and production time to generate an impact…some artisans have helped us by providing product for several fairs; however, we have seen that the local production is not in an optimum level to compete internationally, nor to export” (A12, Owner of a small social enterprise of handcrafts).

The financial supply chain encompasses the financial institutions that support the physical supply chain (Carter et al. 2015). In the Mexican context, the lack of access and distrust towards banks was the most evident challenge to the financial supply chains of social enterprises. First, the majority of supply chain stakeholders make and accept payments only cash-in-hand. This phenomenon may be explained from the overarching concept of “informal economy”, which is common in developing countries. Drawing on this concept, it is possible to deduce that suppliers, distributors and social entrepreneurs are reluctant to formalize their economic activities because they do not perceive that the benefits will be higher than the costs of the economic formalization (Williams and Nadin, 2014).

"We hardly accept credits, we do everything by ourselves ... When the bank offered to give us a financing, they told us about a certain amount of money. There was a person which was managing the process, he works for the bank… at the end, he requested the 15% of the final amount. The problem is that when we had our meetings, they told us we should not give money to anyone. When you face this type of situation, problems may begin” (A7, Owner of a medium-sized restaurant)

Second, there is a lack of access to financial capital from banks and financial institutions. Specifically, most of the interviewees indicate that in the Mexican context is very difficult to consider the bank as a strategic allied. Suppliers, distributors and social enterprises alike have faced difficulties in fulfilling all the requirements demanded by the bank in order to get a financial credit. Besides, banks charge high interest rates to the financial credits, which represent a big financial burden almost impossible to bear by small and medium social enterprises. The government could be the alternative to get funding for social enterprises, but financial support is often granted to large enterprises. This situation is in line with Walske and Tyson (2016) findings of the limited role of the government in helping younger social enterprises.

"In one occasion, my accountant told about an event that helps entrepreneurs with financing. When I went, they mentioned governmental and bank support…as soon as I went to the bank, they told me that they could lend me the money in exchange for showing a monthly income of $100,000.00 MXN… obviously this condition is not made for social entrepreneurs” (A10, Manager of a small social enterprise of textiles).

Alike to the financial supply chain, the informational supply chain serves as a support for the physical supply chain (Carter et al. 2015). Based on the interviewees’ answers, it was possible to identify two contrasting sides of the informational supply chain. The first one is a positive side related to the benefits brought by information and communication technology advances. Distance is no longer a limitation to keep communication with people. For social entrepreneurs, it was easy to communicate with their rural suppliers and distributors through diverse means such as WhatsApp, SMS (short message service), electronic mail and Facebook.

“They (suppliers and distributors) have my email, Facebook and WhatsApp. It is very easy to communicate nowadays” (A4, Owner of a small social enterprise of textiles).

However, there is also a negative side related to the lack of communication infrastructure in remote areas. Especially, the limited internet and telephone coverage in rural communities hinder the capacity of suppliers for being in constant communication with distributors and social entrepreneurs, which in turn affect the effective coordination of the supply chain. In extreme cases, the only way of communicating with suppliers located in remote areas is via phone booths and cyber cafes. The inconsistencies in the quality of communication lead to poor interaction among supply chain stakeholders. Hence, this dynamic affects the formation of social capital, which is fundamental for scaling social impact (Bloom and Smith, 2010).

“In one occasion a client asked for 25 large boxes and I did not have the complete product. The supplier is in the Sierra del Pacífico ... it is a wooded area and there are not many inhabitants… there is no telephone signal. I needed to get in touch with him, but he only comes to the city on Saturdays… without seeing him, it was impossible to establish communication. So, I decided to call either a cabin or a small hotel… There are communication problems, but you need to find a way to communicate” (A9, Owner of a small social enterprise of handcrafts).

The main goal of this article was to comprehend how social entrepreneurs in developing countries deal with the challenge of managing the supply chain in order to scale social impact. Findings indicate that supply chain management turns complex for social entrepreneurs due to barriers imposed by both internal and external sources. The internal sources encompass limitations of supply chain stakeholders such as limited production capacity, poor delivery performance and ineffective inventory management. These processes are crucial for the correct operation of a supply chain, so social enterprises should prioritize the improvement of these processes to scale social impact.

However, interviewees did not seem totally convinced of the relevance of supply chain management to scale social impact. Instead, they expressed their preference to allocate resources in other opportunity areas rather than focusing on strengthening the supply chain. In this case, it is needed that social entrepreneurs consider supply chain development as a top priority. This action implies a process of constant collaboration and mutual learning with supply chain stakeholders about the best practices of supply, production and distribution in order to reduce extra costs, generate value and achieve scalability (Desa and Koch, 2014; Yunus et al. 2010).

In line with the argument previously mentioned, social entrepreneurs must widen their conception of scalability to not just a product level but to a whole business approach. In order to reach scalability, all the aspects of the social business model must improve, especially those related to supply chain management such as manufacturing, logistics and distribution (Prahalad, 2012). Raising awareness among social entrepreneurs about the relevance of the supply chain management may be a useful strategy that can be implemented whether through social incubators or public institutions.

Regarding the external sources, these seem to be more difficult to overcome without governmental intervention. The lack of transport and telecommunication infrastructure is a common problem that affects supply chain management in developing countries (Pires, 2015). Hence, social entrepreneurs must act as “social bricoleurs”, that is, they need to find creative ways of solving supply chain problems with resources at hand. Again, the first step is the recognition by social entrepreneurs about the relevance of supply chain development, so they can be open to invest in, for instance, the provision of low-price cell phones to their supply chain stakeholders (see Haggblade et al. 2007).

Yet, the most pervasive barrier to overcome in developing countries is the prevalence of an inflexible financial structure. Financial institutions are not a viable option to get funding for both social enterprises and rural suppliers due to the complexity and high-risk implications of accepting a credit loan with high-interest rates. In such a scenario, government departments must have a more relevant role in the provision of affordable and easily accessible loans to social enterprises. This implies a substantial transformation in financial institutions infrastructure and government policies in order to support the scalability of social enterprises (Bengo and Arena, 2019).

The current research was focused on analysing how social enterprises operating in developing countries deal with the challenge of managing their supply chains in order to scale social impact. Interviews held with founders and managers of Mexican social enterprises shed light on the different barriers they face to effectively develop a strong supply chain. Most of the barriers identified during the fieldwork are mainly prevalent in developing countries such as lack of transport, communication and financial infrastructure. However, it was also possible to identify barriers related to limited supply chain stakeholders’ capabilities and social entrepreneurs’ disregard on improving the supply chain. Therefore, all of these barriers must be attended in order to support social enterprises in reaching scalability.

This research is not exempt of limitations, which in turn may lead to interesting future research areas. First, the qualitative nature of this research limits its scope to generalize the results. Moreover, interviews were only applied to small and medium Mexican social enterprises operating in specific economic sectors. For future research, it is recommended the development and application of a large-scale quantitative study focused on testing the barriers identified in this research. Likewise, interviews were held only with founders and general managers of social enterprises, so that it would be interesting to include in further research the perceptions of other members (rural suppliers or employees) regarding supply chain management.

Bacq, S., Ofstein, L. F., Kickul, J. R., & Gundry, L. K. (2015). Bricolage in social entrepreneurship: How creative resource mobilization fosters greater social impact. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Vol. 16, Num. 4, Pag. 283-289.

Baxter, P. & and Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers, The Qualitative Report, Vol. 13, Num. 4, 544-559.

Bengo, I., & Arena, M. (2019). The relationship between small and medium-sized social enterprises and banks. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, Vol. 68, Num. 2, Pag. 389-406.

Bloom, P. N., & Smith, B. R. (2010). Identifying the drivers of social entrepreneurial impact: Theoretical development and an exploratory empirical test of SCALERS. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, Vol. 1, Num. 1, Pag. 126-145.

Blundel, R. K., & Lyon, F. (2015). Towards a ‘long view’: historical perspectives on the scaling and replication of social ventures. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, Vol. 6, Num. 1, Pag. 80-102.

Bocken, N. M., Fil, A., & Prabhu, J. (2016). Scaling up social businesses in developing markets. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 139, Pag. 295-308.

Cannatelli, B. (2017). Exploring the contingencies of scaling social impact: A replication and extension of the SCALERS model. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Vol. 28, Num. 6, Pag. 2707-2733.

Carter, C. R., Rogers, D. S., & Choi, T. Y. (2015). Toward the theory of the supply chain. Journal of Supply Chain Management, Vol. 51, Num. 2, Pag. 89-97.

CASE (Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship) (2006). The CASE 2005 Scaling Social

Impact Survey: A Summary of the Findings. Retrieved: February 28, 2019, from https://centers.fuqua.duke.edu/case/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/02/Report_CASE_PSRAI_TheCASE2005ScalingSocialImpactSurvey_2005.pdf

Cavazos-Arroyo, J., Puente-Díaz, R., & Agarwal, N. (2017). An examination of certain antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions among Mexico residents. Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios, Vol. 19, Num. 64, Pag. 180-199.

Desa, G., & Koch, J. L. (2014). Scaling social impact: Building sustainable social ventures at the base-of-the-pyramid. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, Vol. 5, Num. 2, Pag. 146-174.

El Ebrashi, R. (2018). Typology of growth strategies and the role of social venture’s intangible resources. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 25, Pag. 5, Pag. 818-848.

Ellram, L. M., & Cooper, M. C. (2014). Supply chain management: It's all about the journey, not the destination. Journal of Supply Chain Management, Vol. 50, Num. 1, Pag. 8-20.

Gauthier, J., Ruane, S. G., & Berry, G. R. (2018). Evaluating and extending SCALERS: Implications for social entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, Pag. 1-22.

Gonzalez, F.E. (2014). Mexico: Emerging economy kept on a leash by mismatched monopolies, In Looney, R.E. (Ed.), Handbook of Emerging Economies (pp. 287-305). London, UK: Routledge.

Haggblade, S., Reardon, T., & Hyman, E. (2007). Technology as a motor of change in the rural nonfarm economy, In S. Haggblade, Hazell, P.B. & Reardon, T. (Eds.), Transforming the Rural Nonfarm Economy: Opportunities and Threats in the Developing World, (pp. 321-351). Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Ingstad, E. L., Knockaert, M., & Fassin, Y. (2014). Smart money for social ventures: An analysis of the value-adding activities of philanthropic venture capitalists. Venture Capital, Vol. 16, Num. 4, Pag. 349-378.

Koniagina, M. N., Buga, A. V., Kirillova, A. V., Manuylenko, V. V., & Safonov, G. B. (2019). Challenges and prospects for the development of social entrepreneurship in Russia. Revista Espacios, Vol. 40, Num.10.

Lyon, F., & Fernandez, H. (2012). Strategies for scaling up social enterprise: lessons from early years providers. Social Enterprise Journal, Vol. 8, Num 1, Pag. 63-77.

Marshall, C. & Rossman, G.B. (1999). Designing Qualitative Research. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

Newbert, S. L. (2012). Marketing amid the uncertainty of the social sector: Do social entrepreneurs follow best marketing practices? Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, Vol. 31, Num. 1, Pag. 75-90.

Perusquia, J. M., & Ramirez, M. (2019). Motivational differences between countries that underline the intention of millennials towards social entrepreneurship. Revista Espacios, Vol. 40, Num. 18.

Pires, S.R.I. (2015). The current state of supply chain management in Brazil. In Piotrowicz, W. & Cuthberson, R. (eds.). Supply Chain Design and Management for Emerging Markets. (pp. 39-63), Switzerland: Springer.

Prahalad, C. K. (2012). Bottom of the Pyramid as a Source of Breakthrough Innovations. Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 29, Num. 1, Pag. 6-12.

Renko, M. (2013). Early challenges of nascent social entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, Vol. 37, Num. 5, Pag. 1045-1069.

Rivera-Santos, M., Holt, D., Littlewood, D., & Kolk, A. (2015). Social entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa. Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 29, Num. 1, Pag. 72-91.

Scheuerle, T., & Schmitz, B. (2016). Inhibiting factors of scaling up the impact of social entrepreneurial organizations: A comprehensive framework and empirical results for Germany. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, Vol. 7, Num. 2, Pag. 127-161.

Smith, B. R., & Stevens, C. E. (2010). Different types of social entrepreneurship: The role of geography and embeddedness on the measurement and scaling of social value. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, Vol. 22, Num. 6, Pag. 575-598.

Smith, B. R., Kistruck, G. M., & Cannatelli, B. (2016). The impact of moral intensity and desire for control on scaling decisions in social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 133, Num. 4, Pag. 677-689.

Sodhi, M. S., & Tang, C. S. (2016). Supply chain opportunities at the bottom of the pyramid. Decision, Vol. 43, Num. 2, Pag. 125-134.

Tate, W. L., & Bals, L. (2018). Achieving shared triple bottom line (TBL) value creation: toward a social resource-based view (SRBV) of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 152, Num. 3, Pag. 803-826.

Walske, J. M., & Tyson, L. D. (2015). Built to scale: a comparative case analysis, assessing how social enterprises scale. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Vol. 16, Num. 4, Pag. 269-281.

Weber, C., Kröger, A., & Lambrich, K. (2012). Scaling social enterprises–a theoretically grounded framework. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Vol. 32, Num. 19, Pag. 3.

Williams, C., & J. Nadin, S. (2014). Facilitating the formalisation of entrepreneurs in the informal economy: towards a variegated policy approach. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, Vol. 3, Num. 1, Pag. 33-48.

Wulleman, M., & Hudon, M. (2016). Models of social entrepreneurship: empirical evidence from Mexico. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, Vol. 7, Num. 2, Pag. 162-188.

Yunus, M., Moingeon, B., & Lehmann-Ortega, L. (2010). Building social business models: Lessons from the Grameen experience. Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, Pag. 2-3, Pag. 308-325.

Zajko, K., & Bradač Hojnik, B. (2018). Social franchising model as a scaling strategy for ICT reuse: A case study of an international franchise. Sustainability, Vol. 10, Num. 9, Pag. 3144.

1. Research Associate at the Department of Management and Marketing. UPAEP University. fernandorey.castillo@upaep.mx

2. Research Associate at the Department of Management and Marketing. UPAEP University. judith.cavazos@upaep.mx