Vol. 40 (Number 12) Year 2019. Page 23

Vol. 40 (Number 12) Year 2019. Page 23

PROKHODA, Vladimir A. 1; KURBANOV, Artemiy R. 2

Received:03/01/2019 • Approved: 26/03/2019 • Published 15/04/2019

ABSTRACT: This article deals with the results of a cross-country comparative sociological study. It is noted that there is a statistically significant direct correlation between the attitude of respondents to migrants and the level of their education in all European countries included in the study, except Russia, the Russians perceive migrants rather negatively. It concludes that the contemporary Russian high school fails to implant the sociocultural behavioral patterns that contribute to shaping a tolerant attitude towards migrants. |

RESUMEN: Este artículo analiza los resultados de la investigación sociológica comparativa entre países. Se observa que existe una correlación directa estadísticamente significativa entre la actitud de los encuestados hacia los migrantes y el nivel de educación en todos los países europeos incluidos en el estudio, excepto en Rusia, los rusos perciben a los migrantes de manera bastante negativa. Se concluye que la educación superior rusa moderna no es capaz de introducir comportamientos socioculturales que promuevan la formación de una actitud tolerante hacia los migrantes. |

Migration-related issues, in particular those regarding the integration of migrants into the host community, are rather essential for many nations. The labor market of global cities offers not only high-paying jobs today but also low-paid ones, so an increase in the migration flow is inevitable (Dobrinskaya et al, 2018). European countries and cities are no exception. The European migration crisis of 2015 is quite illustrative due to the failure of many European countries to control and redistribute an increasing number of migrants from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia. The study is focused on the role of higher education in shaping the public attitude towards external migration. The current extent of the migration crisis in Europe demonstrates the importance of education, especially higher education, as a factor in shaping social and behavioral attitudes towards various social phenomena, one of which is migration. A number of European leaders recognize the failure of the multiculturalism policy. This fact may affect the value matrix that determines the education system. Such approach to resolve the issue is of particular importance, since it is highly literate citizens that determine the social dynamics. Note that our study does not cover aspects of the public attitude towards internal migration, or migration of people from one region to another within one country.

There is a certain lack of scientific research devoted to the study of the correlation between higher education and migrant-related attitudes. The focus is usually on other aspects, such as economic (Citrin et al, 1997), cultural, ethnic, or gender aspects (Berg, 2010). The article

“Educated Preferences: Explaining Attitudes toward Immigration in Europe” by Heinmüller and Hiscox (2007) is an example of the research work covering the correlation of education, especially higher education, with migrant-related attitudes. The research suggests that anti-immigrant attitudes are common among poorly educated or less qualified citizens who fear labor competition with immigrants. The researchers conclude that better educated people demonstrate a positive attitude towards immigration more often. Heinmüller and Hiscox emphasize that there is a direct correlation between pro-immigration attitudes and higher education in European countries. The authors note that, in general, migrant-related attitudes are caused by cultural and ideological differences, rather than by economic reasons. Better educated respondents are less susceptible to racist prejudice and tend to lay more emphasis on cultural diversity than poorly educated people. College educated people are convinced that immigration is beneficial for the economy of the host country.

One of the recent studies on this issue was published in The European Economic Review in 2016. Its authors noted a positive correlation between the education level and migrant-related attitudes. Using the data provided by the European Social Survey and the Labor Force Survey for the period from 2002 to 2012, the authors conclude that a higher level of education results in a more pro-immigrant attitude, since education contributes to the transformation of values and cognitive assessments of the immigration role in the host communities (D'Hombres and Nunziata, 2016).

Domestic empirical research data are quite contradictory. Some research findings state that college educated Russians more often note negative aspects of migration, and there are more supporters of restricting migration from other countries among them (On attitudes towards migrants, 2014). The researchers state that people having high-school or college education tend to express more radical opinions on newcomers, explaining that "...the middle class consumes more media products" (Own - a stranger, 2013). However, the results of other studies state that poorly educated Russians tend to feel more hostile towards migrants than better educated people (Bessudov, 2010). Moreover, according to the comparative study of social determinants of migrant-related attitudes in Estonia and Russia, such characteristics as age, sex and education do not effect migrant-related attitudes in Russia as compared to Estonia. The authors state that there is a direct correlation between the education level and migrant-related attitude in Estonia (the higher the education level, the better the attitude), but the education level is not a statistically significant factor in this context in Russia (Demidova et al, 2014). Some recent studies state that social, professional, educational and age differences are less important for determining migrant-related attitudes in Russia as compared to countries such as the United Kingdom and France (Klupt, 2018).

Objective of this article is to identify the nature of the correlation between higher education among residents of European countries and their migrant-related attitudes.

The research is based on the results of Round 8 of the European Social Survey (ESS) conducted in 2016 (ESS Round 8: European Social Survey Round 8 Data, 2016). The ESS is a project in which paradigms, attitudes, values and behavior of the European population have been surveyed since 2002 (Russia has been participating in the ESS since 2006). The survey covers the population at the age of 15 and older. The method for collecting primary sociological information includes interviewing respondents face-to-face at their homes. The list of participating countries varies depending on the survey year. A number of respondents (from 880 in Iceland to 2852 in Germany) were surveyed under the national representative sample. 2430 people were surveyed in Russia. The data from 23 countries were analyzed. Although Israel is located in Asia, it was included in the survey, since the country is substantially integrated into the European cultural and economic space.

Apparently, educational institutions have a key impact on the development of the value system and of the framework of the human social behavioral system. The formation of a global educational space, especially at the level of higher education, results in the unification of educational strategies, models, key objectives and competencies acquired in the learning process. The implementation of the Bologna agreements resulted in the creation of a single European educational space. The higher education systems of European countries were integrated not only at the institutional design level, but, above all, in terms of priorities in the implementation of their educational programs. The latter include competences related to the integration of a person in a multicultural society.

The transformation of the Russian higher education system in accordance with the principles proclaimed in the Bologna Declaration suggests the possibility of comparing the results of its impact on key social attitudes of Russian citizens with similar indicators of higher education systems in countries within the European educational space. Meanwhile, a special methodology is required for a meaningful comparison of the educational levels of respondents with due account for the current national specifics.

Respondents were asked the following question to define their educational background: "What is your highest level of education?" The respondent's level of education was measured in each country in accordance with the categories established in the national education system. Although this approach affords effective analysis in a national context, it has significant limitations when comparing national levels with each other (Andreenkova, 2014).

The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) was introduced to ensure data comparability across countries. The classification adopted by UNESCO in 1997 was used as the standard one in the ESS (International Standard Classification of Education, 2013). Experts from different countries and an international group have developed a new International Classification of Education (ES-ISCED) based on the ISCED. There are seven education stages distinguished within its framework with higher education included in the last two stages: "First stage of tertiary education" and "Second stage of tertiary education" (Schneider, 2008).

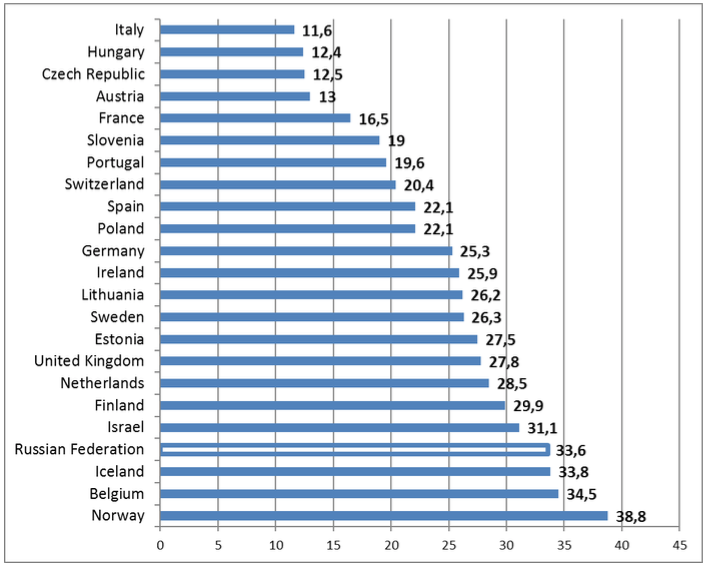

Taking into account the specifics of higher education levels in Russia in comparison with the ES-ISCED system, we created a binary variable dividing all respondents into two categories. The first category included respondents having a college degree (which corresponds to the last two ES-ISCED stages). These were Russian respondents who graduated with a bachelor’s degree after four years of study, or graduated with a master’s degree after additional two years of study, or got complete higher education in the 5- or 6-year education system, as well as respondents having a scholastic degree. All other respondents were attributed to the second category. The percent of college educated respondents in each country is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1

Percent of college educated respondents of the

total number of respondents in each country

The findings of the study state that European countries differ in terms of the percent of college educated population. E.g., the percent of college educated respondents in Italy and Norway (minimum and maximum European indicators) differs by more than 3.3 times. If we look at the indicator under consideration, Russia is in the group of leading countries, along with Norway, Belgium, Iceland, Israel, Finland, the Netherlands.

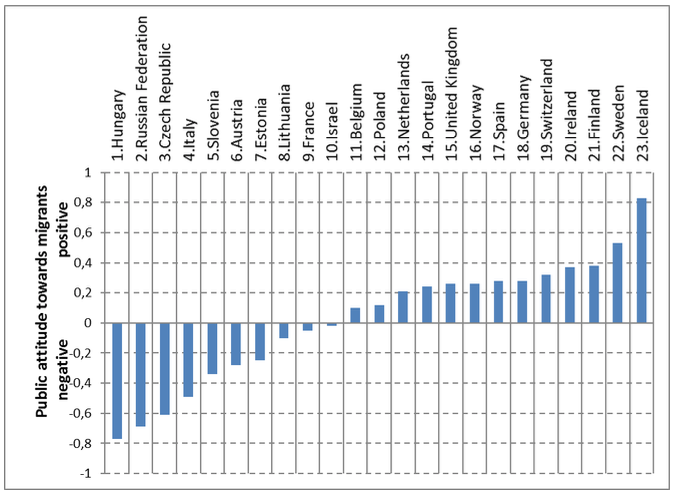

The survey divided the impact of migration on the social welfare in the country into two sublevels: the impact on the economy and the impact on the culture. Respondents were asked the following questions: "Do you think the fact that people from other countries migrate to our country, in general, favorable or unfavorable for its economy?"; "Do you think the migratory influx from other countries is more likely to destroy or rather enrich the national culture?"; "Do you think the living conditions improve or get worse in our country with the migratory influx from other countries?" Answers were given according to the 10-point scale, where "0" stood for a negative impact ("unfavorable for the economy," "destroys the national culture," "get worse"), "10" stood for a positive influence ("favorable for the economy," "enriches the national culture," "improve").

The factor analysis (Extraction Method — Principal Component Analysis; the total explained variance — 79.9%; Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy = 0.738; Bartlett's Test of Sphericity — p<0.001) revealed the possibility of combining all three variables into an integrative index (factor) notionally named the "migrant-related attitude." Then the countries participating in the ESS 2016 were ranked in ascending order of the average factor value. Countries with more positive public migrant-related attitudes had higher ranks. The positions of countries in the reference system in accordance with their ranks (from the least positive to the most positive public attitude towards migrants) are shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2

Public attitude towards migrants in European countries (ranking by the average factor value:

the more positive the public attitude to migrants is, the higher the country ranks)

Iceland (Rank 23) is located on an island far from the mainland and near the Arctic Circle. Its geographical position is a natural obstacle to a large migration gain. Its population does not actually face the large-scale negative impact of migration, which largely predetermines public migrant-related attitudes in Iceland.

Sweden (Rank 22) stands out among other countries. Its community demonstrates a prominent positive attitude towards migrants. A liberal migration policy combined with a high standard of living and the willingness of the local community to welcome visitors make Sweden attractive to immigrants. The influx of immigrants is quite intensive, and the local community has vast experience in dealing with immigrants, including those from poorer countries. The fact that the host community itself is very diverse in its composition certainly influences the respondents' attitudes. Every sixth citizen of modern Sweden was born in another country. A significant part of its inhabitants are second- or third-generation descendants of immigrants. Pro-immigration attitudes are based on some objective grounds. According to official sources, the national economy needs an annual influx of 64,000 immigrants aged 16–64 (Rapport från Arbetsförmedlingen, 2015).

There is a definite correlation between the public attitudes and the homogeneity of the host community. The population of such countries as Sweden and Germany (Rank 18) has vast experience in communicating with migrants of different nationalities, and at the same time demonstrates a pronounced positive attitude. It is rather peculiar that there are quite a lot of migrants living in France (Rank 9) as well, but its community treats migrants much worse. This can be explained by the struggle for independence which the French colonies were participants of in the middle of the 20th century, especially by the Algerian War and the migration influx from North Africa caused by these events (Scullion, 1995).

Negative attitudes are also characteristic of the so-called "transit" countries (Italy, Slovenia, Austria), which act as transfer points, as their borders are crossed by illegal migrants trying to get into the destination country. Hungary (Rank 1), Russia (Rank 2) and the Czech Republic (Rank 3) were among the outsiders with the lowest figures in Europe on the extemporaneous list. The obtained results are rather stable, as evidenced by the ESS 2014 data (Prokhoda, 2017). There are various explanations for negative public attitudes. Some of the listed countries, such as the Czech Republic, have a relatively small percent of migrants, which assumes stereotypical perception patterns due to the lack of interpersonal contacts. In countries characterized by large migrant communities, such as Russia, the public attitude is largely determined by the integration degree, including the intention of the immigrants to become part of the host community.

Anti-immigrant attitudes in Russia may be explained by reviewing the results of other sociological studies. The research state that there is a widespread opinion in Russia that immigrants create competition in the labor market and "steal" jobs from local residents (Immigration to Russia, 2013). Due to that, most Russians are rather negative about migrants occupying various economic sectors, except public services and the tertiary sector (Migrants in the Russian labor market, 2016). The anti-immigrant attitudes may also be caused by the popular opinion that migrants have no intention to adapt to the social environment. The host majority is repelled by the lack of respect for the customs and traditions of the host community. Russian people are wary of the cultural isolation of various migrant communities, which, in its extreme form, may lead to the development of self-contained national enclaves not fitting into the cultural sector (Conditions and price of migrants’ integration, 2012). A significant part of the population considers migration to be related to the crime rates (Migrants in Russia, 2016).

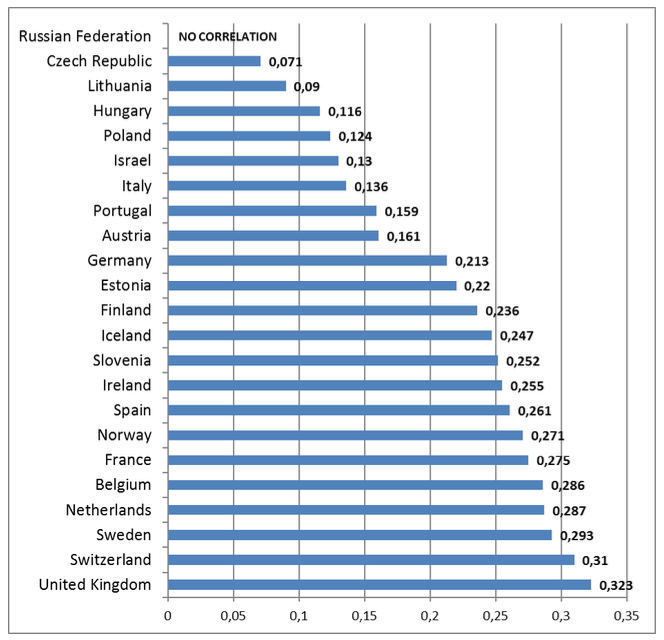

Subsequently, the correlation coefficient between the integrative indicator characterizing the migrant-related attitude and the availability of the college degree with the respondent was calculated using the correlation analysis procedure (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3

Correlation between the public migrant-related attitude in European countries and the

availability of the college degree: Spearman's rank correlation coefficient value

(from "0" — the indicators are independent, to "1" — the rank sequences coincide completely)

The data obtained is indicative of a statistically significant direct correlation between the attitude of respondents to migrants and the level of their education in all European countries included in the study, except Russia. In other words, college educated respondents treat migrants more positively in all countries, except Russia. This is quite consistent with our previously published ESS 2014 results characterizing the dependence of the public attitude in European countries on the education level, which indicates the sustainability of the results obtained (Prokhoda et al, 2017).

The most evident dependence is demonstrated in the UK, Switzerland, Sweden, the Netherlands, Belgium. Apparently, the education system of these countries successfully fulfils the social order for the development and maintenance of values and competencies necessary for intercultural social interaction. It is rather peculiar that the minimum values of the correlation coefficient are registered in the former socialist countries (Czech Republic, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland).

There are various interpretations of the results. It is obvious that higher education is aimed at developing and maintaining skills, values and competencies necessary for intercultural social interaction. We can assume that the contemporary Russian high school fails to implant sufficient sociocultural behavioral patterns that contribute to shaping a tolerant migrant-related attitude.

Mass media is becoming a potential tool for shaping migrant-related attitudes. As a rule, mass media depicted migrants in a quite adverse style in post-Soviet Russia. Being a significant part of everyday communication of Russian people, this information context could become a more significant factor shaping migrant-related attitudes than a college degree (Fedorov, 2014).

Social effects of the tragic events that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of the new Russian state system (ethnic conflicts of the late 1980s — early 1990s, Chechen Wars I and II), combined with a certain information background, could influence the formation of migrant-related attitudes stronger than the education system, despite the gradual development of the tolerance discourse in the educational space. It can be assumed that the influence of educational institutions turned out to be less significant than the impact of other agents of socialization.

The disputed issues may include the question of how, in principle, the fact of having a college degree can be differentiating in terms of shaping social attitudes, including migrant-related attitudes, in the Russian Federation, taking into account the coverage of the population by this institution. According to the data provided by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development for 2015 (Educational Attainment and Labour-force Status, 2018), the percent of college educated people in the 25 to 64 age group in Russia is 53.1%. This indicator is significantly higher in the Russian Federation as compared to all other countries mentioned herein. E.g., according to the same source, this indicator does not exceed 35% in most European countries.

With such coverage rates of higher education in Russia, we can speak of its massification, which may lead to a decline in the quality of education, especially in the formation of social competence. A number of researchers note that the mass nature of education in Russia has led to free access to third-rate colleges and limited access to elite ones (Kostyukevich, 2012). It can be assumed that the impact of higher education on the social attitudes of Russian people can be observed through a deeper analysis distinguishing groups of colleges in terms of the quality of education.

The minimum values of the correlation coefficient between the public migrant-related attitudes in European countries and the education level registered in some former socialist countries (Czech Republic, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland) can be explained, on the one hand, by the predominantly mono-ethnic and mono-cultural characteristics of their communities. This can be considered a factor unifying the functions of socialization institutions to a certain extent. On the other hand, these countries were partially isolated from migration flows for historical reasons, and, conversely, were a source of labor migration before being included in the European political and cultural space.

The review of the in-country information context could be more demonstrative as to the key characteristics of the migrant image created by the national mass media. At least two of the listed countries (Czech Republic and Hungary) are currently assuming an extremely tough attitude with regard to the common European migration policy, regarding migrants as a threat to the cultural identity of their communities. It can be assumed that in this case the migrant-related attitude becomes one of the basic social attitudes formed by all major institutions, and the education system can convey the existing social attitudes. In this regard, the issue with the Central European University (CEU) in Budapest, founded by George Soros, is of great interest. The University is currently changing its location (classes are transferred to Vienna) due to the amendments to the education legislation adopted by the Parliament of Hungary in 2017. Such actions can be considered as a protectionist policy in relation to the national education system. Concurrently, the Hungarian Parliament approved a package of bills aimed at fighting illegal immigration (informally called the "Stop Soros" Law) in 2018. The measures proposed by the government include restricting the movements of illegal immigrants throughout the country and criminalizing organized assistance to them.

In conclusion, we would like to note that the publication addresses only certain aspects of the declared problems. Apparently, the issue under consideration deserves more efforts and attention. Certain challenge may be found in reviewing the correlation of migrant-related attitudes not only with higher education, but with the overall education level of respondents. Certain characteristics of higher education institutions (e.g., their position in national and international ratings) may be studied as well.

ANDREENKOVA, A.V. (2014). Comparative cross-country studies in the social sciences: theory, methodology, practice. Moscow: New Chronograph. 516 p. (In Russ.).

BERG, J. A. (2010). Race, Class, Gender, and Social Space: Using an Intersectional Approach to Study Immigration Attitudes. Sociological Quarterly, 51(4): 278–302.

BESSUDOV, A. (2010). Where migrants are loved, and where are not. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from https://republic.ru/russia/gde_migrantov_lyubyat_a_gde_net-471618.xhtml. (In Russ.).

Conditions and price of migrants’ integration. (2012). Fund Public Opinion. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from http://fom.ru/Obraz-zhizni/10465. (In Russ.).

CITRIN, J., GREEN, D.P., MUSTE, C. (1997). Public Opinion toward Immigration. Reform the Role of Economic Motivations. The Journal of Politics, 59(3): 858–881.

D׳HOMBRES, B., NUNZIATA, L. (2016). Wish you were here? Quasi-experimental evidence on the effect of education on self-reported attitude toward immigrants. European Economic Review, 90: 201-224. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.02.007.

DEMIDOVA, O.A., PAAS, T. (2014). How people perceive immigrants’ role in their country’s life: a comparative study of Estonia and Russia. Eastern Journal of European Studies: 5(2): 117-138.

DOBRINSKAYA, D., VERSHININA, I. (2018). New Connectography: Networks of Cities in the Global World. Revista ESPACIOS, 39(16). Retrieved 23 December 2018, from http://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n16/18391607.html

ESS Round 8: European Social Survey Round 8 Data. (2016). Data file edition 2.0. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC.

Educational Attainment and Labour-force Status, OECD. (2018). Education at a Glance. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=EAG_NEAC.

FEDOROV, P.M. (2014). Role of mass media in forming social attitudes of Russians regarding migrants (based on the content analysis of regional online news sources). The Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes Journal, 6(124): 119–134. (In Russ.).

HAINMUELLER, J., HISCOX, M. J. (2007). Educated Preferences: Explaining Attitudes toward Immigration in Europe. International Organization, 61(2): 399–442

Immigration to Russia: good or harm for the country? (2013). Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM), press-release No. 2360. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=114322. (In Russ.)

International Standard Classification of Education. (2013). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from http://www.uis.unesco.org/education/documents/isced-2011-ru.pdf. (In Russ.)

KOSTJUKEVICH, S.V. (2012). Higher education: some modern world-wide tendencies. Sociological Almanac, 3: 103–114. (In Russ.)

Migrants in Russia: effects of presence. (2016). Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM), press-release No. 3254. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from http://old2.wciom.ru/index.php?id=459&uid=115969. (In Russ.)

Migrants in the Russian labor market: pro et contra. (2016). Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM), press-release No. 3072. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from https://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=115643. (In Russ.)

On attitudes towards migrants - internal and external. (2014). Fund Public Opinion: FOMnibus weekly survey, May 31 - June 1, 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from http://fom.ru/Nastroeniya/11566. (In Russ.)

Own - a stranger. More and more Muscovites believe that there is only harm from migrants. (2013). Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 6269 (293). Retrieved 23 December 2018, from https://rg.ru/2013/12/26/migranty.html. (In Russ.)

PROKHODA, V. A. (2017). European Population Attitude Towards Migrants. Humanities and social sciences. Bulletin of the Financial University, 2: 64–71. (In Russ.)

PROKHODA, V. A., KURBANOV, A. R. (2017). Higher education in the context of social attitude formation (by the example of the European population attitudes towards migrants). Values and Meanings: 4: 8–19. (In Russ.)

Rapport från Arbetsförmedlingen. Hög nettoinvandring behövs. (2015). Retrieved 23 December 2018, from https://www.arbetsformedlingen.se/Omoss/ Pressrum/Pressmeddelanden/Pressmeddelandeartiklar/Riket/2015-04-10-Hog-nettoinvandring-behovs.html#.VuwKJOLhCUm.

SCHNEIDER, S. L. (2008). Nominal comparability is not enough: Evaluating cross-national measures of educational attainment using ISEI scores. Sociology Working Papers Paper. Department of Sociology University of Oxford: 2008–04. Retrieved 23 December 2018, from https://www.sociology.ox.ac.uk/materials/papers/2008-04.pdf

SCULLION, R. (1995). Vicious Circles: Immigration and National Identity in Twentieth-Century France. SubStance: 24(1/2): 30–48. DOI:10.2307/3685089

1. Department of Sociology, History and Philosophy. Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow; Department of Philosophy. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow. Chair of Philosophy of Education. Contact e-mail: prohoda@bk.ru

2. Department of Philosophy. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow. Chair of Philosophy of Education. Contact e-mail: ark112@yandex.ru