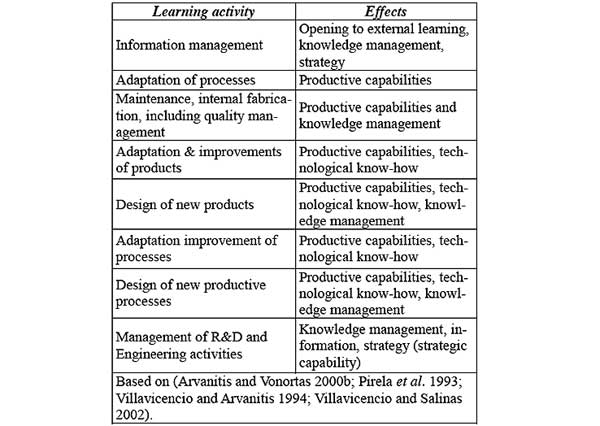

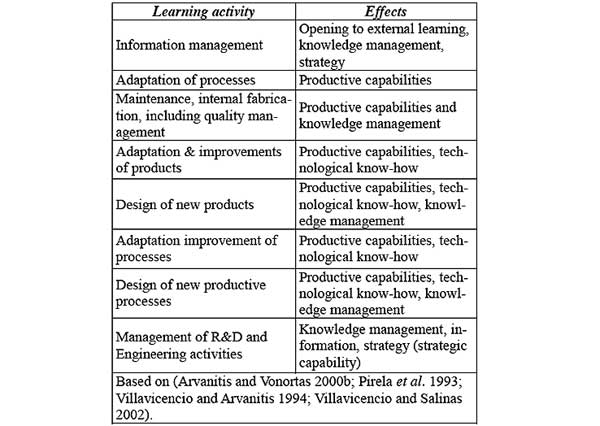

Table 1.

Internal learning experiences and effects on capabilities of the enterprise

| ABSTRACT: This article examines the basic change of the last twenty years in China, that is the creation of industrial entreprises. Six case studies of technological learning and links to external sources of know-how from the South of China in the Pearl River Delta are examined. It is shown that the learning process although rapid is now at the crossroads. Until now entreprises have acquired technology through external linkages to foreign providers and clients. They should need to up-grade their technology, a task that needs to undergo more in-depth changes. We finish by highlighting some of the problems we have found such as the absence of an innovation policy, a fragmentation of initiatives, a lack of technological links between companies and technical or innovation centers. |

RESUMEN: El artículo examina el principal cambio que a conocido China en los últimos veinte años, a saber el crecimiento de las empresas industriales. Seis estudios de caso de aprendizaje tecnológico se presentan con vínculos externos en la región del Delta del Rió de las Perlas en el Sur de China. Se muestra que el proceso de aprendizaje esta hoy en una encrucijada. Hasta hoy las empresas han adquirido la tecnología a través de relaciones a los proveedores extranjeros y los clientes. Si quieren mejorar sustancialmente su tecnología deben pasar por cambios más profundos. Se muestran a continuación algunos de los problemas que se encuentran como la ausencia de una política de innovación, la fragmentación de iniciativas y la ausencia de vínculos tecnológicos entre empresas o entre empresas y centros de innovación. |

||

China has known an impressive 8% annual growth in recent years and its GDP has been multiplied by seven in the last 23 years. Still the size of the country blurs the extraordinary diversity of situations. Recent growth began after the reform period, at the beginning of the eighties. It relied in an important growth of the non-planified sector, that is productive systems that were not planned by the government authorities. Three waves of investment were responsible for this new emerging economy. The first one, in the early eighties, saw the appearance of township and village entreprises, mainly in rural settings. It was a growth that was impulsed at the lowest levels, by personal initiatives.

It went on from 1983 to 1988. This divine surprise was followed by a second wave of investments mainly by foreign Chinese, from Taiwan and Hong Kong that introduced productive systems which were formerly situated in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

These foreign investments represented 18% of investment in China in 2001 (around 20 billion dollars), and 47.5% of Guangdong Province foreign investment (around 6.9 billon dollars). This wave of investment was to be durable wouldn’t there have been the 1997 Asian crisis that hit Asian investment. It was relayed by a third wave of investment mainly coming from the USA and Europe, and Japan. This last wave is still going on. On the whole there are 212,436 foreign entreprises (by JV or totally owned).

At the same time China sees an impressive growth of its private sector. In 1998, there was 1.8 million entreprises “private entreprises” (seyin qiye).2 This does not count for individual entreprises (getihu) which were, until 1988, the only entreprises allowed legally (since 1981), which are entreprises of less than seven employees (31.6 million units). The overwhelming majority of private entreprises has been created after the tour in the South of Deng Xiaoping, in January 1992. This explains why today there is still is a substantial collective sector, neither state-owned nor totally private which is managed in a private way (3.2 million entreprises). The State owned entreprises are gathering more than 1.6 million entreprises3. Some state-owned entreprises can be “privately managed” (mingying) and this concerns more high-tech entreprises or companies created by scientists, academics, universities and research centers.

On the whole, much of China’s economic development is due to its industrial growth. Chinese economy is still export-driven and relies heavily on foreign investment. But the growth itself has been shown to be largely due to a combination of various factors, of which an important part relies on the entrepreneurial growth of China. This emerging economic sector is composed mainly with Chinese owned companies. In fact, as we will show, even collective and private entreprises have a strong incentive in finding either foreign partners participating directly in the management and the capital of the entreprises or foreign clients that act as foreign providers of technology.

A lot of discussion is taking place on the reasons of this growth and its sustainability. Moreover, is this growth possible in other countries in Asia or elsewhere –for example Latin America? How much of it is exceptional, that is how much of it can be understood as being specific to the specific political conditions of China (a former communist country, a “transition economy”, a gigantic economy dominated by the state or whatever you choose as a qualification) and the specific “advantages” of the country (low labour cost, easy and rapid creation of business, sizable newly merging markets).

Our article will try to present in an articulate way one of the essential aspects of this growth process: the relations of China with the economies of the rest of the world. Our cases are all from Guangdong province in the South of China, which is responsible for more than 36% of China’s exports and 14% of China’s production and has been a step ahead in the modernization process of China. Today it still is the main receiver of foreign capital and is still the largest exporter. Its fate is probably the one that could affect all other regions of China in the future. We will use the framework of technological learning in the developing world that has been developed since the pioneering work of Amsden (1989) and Katz (1976) and others in Asia and Latin America because we feel it is useful in understanding a basic component of the Chinese growth: the way businesses are being developed.4 A second aspect, the role of the State, has been repeatedly mentioned, and is subject to much controversy.5 We will deal with it only partially.

The literature on learning has become very large.6 Let us here only remind our own view of learning (Arvanitis and Vonortas 2000b; Pirela et al. 1993; Villavicencio and Arvanitis 1994). First, learning as a process, can be decomposed in two main basic strands: internal learning and external learning.

We call internal learning all the experiences that enhance the products and processes inside the entreprise. This includes activities such as looking at technological information on alternative technological routes, adaptation of in-house technology, development of better and new products and adaptation and design of processes. Product and process innovations, strictly speaking, are part of this learning experience.7 Apart from productive activities, one can mention activities such as R&D, design, engineering, maintenance or quality management. All these affect either the productive capability or the technological know-how of the firms. §he development and management of an R&D unit is quite apart, not only because they develop R&D projects, but also because R&D’s functions are much wider and effectively support the productive process (see Arvanitis 1996; Arvanitis and Vonortas 2000a). R&D, in fact, affects the strategic capability.

As Table 1 shows, our considerations on learning are more empirically based that the ones more sophisticated one can find today in the literature.8 The conceptual refinements imposed by this search for alternate meanings of the learning process seem to us a bit far away from the daily experience of companies. Thus we still use our now ten years old model of learning, first published in English in 1993 in Research Policy.9 We also present in Table 1 a summary of effects of this internal learning on productive capabilities, the technological know-how of the company and the strategic capability.10

Table 1.

Internal learning experiences and effects on capabilities of the enterprise

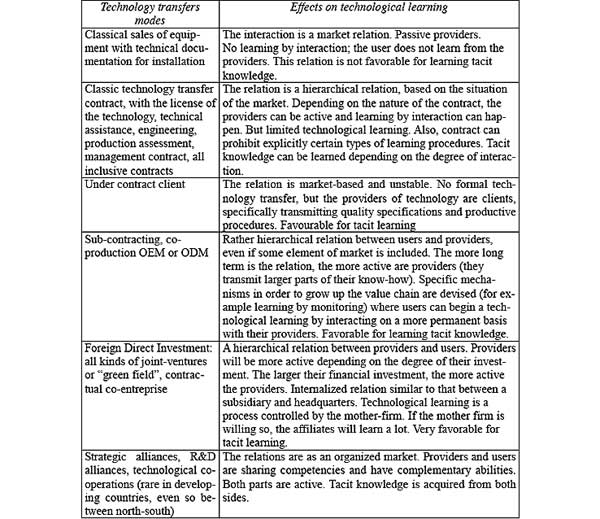

External learning is acquired by interacting with clients, providers, and all kind of socio-economic actors like authorities, experts, etc… Because of the strong rise of collaborative agreements, the analysis of external learning for a long time was considered mainly through the eyes of collaborative technological ventures (Vonortas 1997). But, as Lundvall had correctly stressed, a large array of interactions between the providers of a technology and its users, formed the very basis of learning, or as we believe, of external learning. For developing countries, technology transfers are a form of interaction.

The literature that has grown on technology transfers in the last ten years has been very much enriched by the perspective of “user-provider” (Corona, Dutrénit and Hernández 1994). Moreover, the knowledge transfers that are taking place between a foreign client and a local entreprise are usually left aside and should be included in these interactions as one essential form of technological learning.

Learning activity Effects Information management Opening to external learning, knowledge management, strategy Adaptation of processes Productive capabilities Maintenance, internal fabrication, including quality management Productive capabilities and knowledge management Adaptation & improvements of products Productive capabilities, technological know-how Design of new products Productive capabilities, technological know-how, knowledge management Adaptation improvement of processes Productive capabilities, technological know-how Design of new productive processes Productive capabilities, technological know-how, knowledge management Management of R&D and Engineering activities Knowledge management, information, strategy (strategic capability) Based on (Arvanitis and Vonortas 2000b; Pirela et al. 1993; Villavicencio and Arvanitis 1994; Villavicencio and Salinas 2002).

Table 2.

Effects of different forms of technological transfers on technological learning

Curiously enough, internal learning is much more difficult to observe than external learning as it seems more elusive and very much on the fringe of organizational learning. We have no time here to argue about that, but we believe that there is a strong material learning that needs to be mastered by a company in order to follow-up in a more complex organizational learning (see also (Figueiredo 2002). The insistence on managerial skills will give certainly an advantage but this advantage holds only when material 6 learning experiences have been fully developed.11 All sorts of internal knowledge management practices will have a strong impact on the learning of the company: developing R&D projects, designing new or modified models, design processes and factories layouts, fixing machines and equipment, elaborating maintenance plans, developing quality plans. If a company spends a large part of its time in preparing its internal learning experiences, it will better benefit from the outside sources of knowledge. As these sources grow around the entreprise, it will be able to catch the benefits of these new sources of information.

Finally, the integration of the technological learning with the market will be of paramount importance in the further development of the company. This integration of technology and market is a “soft” skill – an art rather than a science. It is better described as strategic capability which combines the sound internal learning, adequate management of external sources of knowledge and interactions with external sources of knowledge with the analysis of market needs and market evolution. Much of the literature on business strategy focuses on this soft skill, this ability to feel the future needs of the market.12 In brief we can say that learning is always a combination of internal experiences, interactions with external sources of knowledge and the strategic capability of the entreprise.