Vol. 40 (Number 31) Year 2019. Page 21

Vol. 40 (Number 31) Year 2019. Page 21

VOLCHEGORSKAYA E.Y. 1; ZHUKOVA M.V. 2; FROLOVA E.V. 3; SHISHKINA K.I. 4 & KALUGINA E.V. 5

Received: 05/06/2019 • Approved: 31/08/2019 • Published 16/09/2019

ABSTRACT: The article deals with the problem of bullying among children of primary school age on the basis of gender approach. The forms of bullying manifestation, personal characteristics of bullying the participants are investigated. The Multidimensional Peer-Victimization Scale method was used to study the susceptibility to victimization. The sample consisted of 376 schoolchildren aged 10–11 years (198 boys and 178 girls). According to the results of an empirical research, significant gender differences were found in all types of bullying. |

RESUMEN: El artículo aborda el problema del acoso escolar entre los niños en etapa escolar primaria considerando el enfoque en función del género. Se investigan las formas de manifestación del bullying, las características personales del bullying de los participantes. El método de escala multidimensional de victimización por pares se utilizó para estudiar la susceptibilidad a la victimización. La muestra consistió en 376 escolares de entre 10 y 11 años (198 niños y 178 niñas). Según los resultados de una investigación empírica, se encontraron diferencias de género significativas en todos los tipos de acoso escolar. |

In modern school, special attention is paid to the problem of creating a psychologically comfortable and safe environment which ensures a full-fledged process of personal socialization, but the contemporary situation of the societal development is characterized by the emergence of new forms of deviant behavior, among which bullying is a particular concern – situations of violence in an educational institution, the so-called «school harassment». In addition, worldwide decline in the level of mental health is often closely linked with the increasing incidence of physical and psychological violence in the family and educational environment.

According to research, more than 70% of children have been subjected to violence in one form or another. Most frequently (in 75% of cases) violence occurs in the family and school (more than 60% of cases) in the form of beatings, threats, humiliation, neglect and sexual abuse. At the same time, boys are more subjected to physical violence, and girls to contact sexual abuse and to disregard for physical and psychological needs. It is noted that more than 25% of cases of bullying are committed by teachers (Volkova, 2016, Novikova, 2018).

Under Microsoft research, Russia ranks first among the 25 countries in the world in terms of bullying. About 50% of Russian children and young people between the ages of 8 and 17 were subjected to on-line activities that could be described as violent. 49% of respondents are aware of the possibility of harassment in the network, 67% are worried about this, 49% were harassed on-line, 71% - off-line, 86% - both types of violence. Up to 50% of children admit that they have been subjected to violence at least once, and from 2% to 7% - every day. In 2015, the level of victimization among adolescents was 30.2%, and the number of heavy «cyber victims» reached 15.8% (Ortega-Barón, 2018).

It should be noted that the results of cross-cultural studies demonstrate differences in the definition of the concept, perception, forms of bullying manifestation in different cultures (Filatova, 2018).

The term bullying (from the English. Bullying - intimidating) was first used in the United States, where it was understood to be the actions (threats, ridicule, humiliation) that could have a negative effect on a person’s psychological state in order to cause fright, resentment, a sense of humiliation. The first definition of bullying was given by the Scandinavian scientist D. Olvejus in 1993, who defined it as a deliberate, systematically repeated aggressive targeted attempts to inflict harm or discomfort, involving inequality of power and strength, leading to victimization in relation to an individual who is unable to defend himself in a given situation (Olweus, 1993).

According to the National Association of US School Workers definition, bulling should be understood as “dynamic and repetitive patterns of verbal and / or nonverbal behavior producing by one or more pupils towards another pupil, and the desire to harm intentionally, and there is a real or apparent difference in strength” (Glazman, 2009 Maunder, 2018). The studies also use the concepts of “horizontal aggression”, “horizontal violence”, “lateral violence”, “lateral hostility”, and “immunity” (Curtis, 2007, Monks, 2009).

In the conditions of intensive development of information and communication technologies, the phenomena of cyberbullying – violence perpetrated on the Internet or cell phone – have become widespread. Cyberbullying is deliberate acts of an aggressive nature, using the Internet or electronic devices which are regularly committed for some time by an individual or group against a victim who does not have the ability to protect himself (Sindy, 2015, Bochavere, 2014).

The mismatch in statuses between the buller and the victim, the hierarchy, as well as the systematic nature of harassment and a combination of its different types (Butovskaya, 2012), the imbalance in the status of the aggressor and the victim, the orientation of the bullying from the more dominant individual to the more subordinate, as well as the regularity of aggressive actions in time are significant indicators of bullying (Farrington, 1993). The object of harassment is primarily children who differ from most classmates by their appearance (anthropological features, accent or speech defects, differences in dress or behavior), they are weak and unable to protect themselves (Butovskaya, 2012).

Various studies emphasize that manifestations of bullying increase from preschool childhood to the time of transition from primary to secondary school and further decrease by the end of adolescence (Sumter, 2015; Huitsing, 2018). In girls, manifestations of bullying decrease from 11% (11-13 years) to 8% (15 years), in boys from 14% (11 years) to 9% (15 years) (Online Bullying Among Youth 8-17 Years Old, 2019).

There is a view that bullying is one of the indicators of the normal process of children’s socialization and the manifestation of competition in their environment, which forms the masculinity of boys and allows children of both sexes to achieve high results in the future (Berdyshev, 2011, Álvarez-García, 2017).

As violence presupposes the existence of a children's community, there are several roles of this system: the abuser (rapist, oppressor, aggressor), the victim (oppressed), the witnesses (bystanders) which can be played by adults and children. Often, children who have experienced the role of the victim later become abusers themselves (Walters, 2018).

As a rule, negative consequences for personal development are common for all participants in bullying, which include the increase in depressive symptoms, suicidal tendencies, post-traumatic stress (Álvarez-García, 2015; Patterson, 2016), disorders of psycho-emotional development (Krivtsova, 2016), the loss of academic motivation leading to abandonment of school visiting. (Oldenburg, 2015), difficulties of adaptation in adulthood, the increased risk of addictive behavior (the use of psychoactive substances, the dependence on virtual reality of computers, eating disorders) (Kretschmer, 2017; Holt, 2015), a low level of satisfaction with life (Sumter, 2015).

For aggressors, the criminalization of behavior is the most common consequence, for victims - health problems, suicides, for bystanders (adult people) - loss of professional or parental competence. However, it should be noted that the manifestations of cruelty in the children's environment are very diverse in degrees of intensity and in types.

There are two groups of bulling manifestations: active, suggesting active forms of harassment and isolating, associated with the exclusion of the victim from the system of interpersonal relations. Bullying occurs in different forms: physical (beatings, kicks and pinches, various types of injuries, actions of a sexual nature); psychological (impact on the victim's psyche through threats, insults, intimidation, isolation, extortion, damage to property, cyberbulling) through verbal or non-verbal means (Bochavera, 2013).

As a rule, the aggressors are individuals who are characterized by self-confidence, a tendency to domination, physical and moral strength, high status in the group. Victims are characterized by low stress tolerance, extreme self-doubt, low self-esteem, and inability to resist.

There are quite a lot of studies devoted to studying the positions of participants in bullying (Yermolova, 2015; Rigby, 2016), reasons of school harassment (Deryabina, 2017; Pečjak, 2017; Rigby, 2016), factors of bullying (Nesterova, 2018; Butenko, 2015; Yermolova, 2015; Obukhova, 2017; Volikova, 2015; Bochavere, 2013), features of national and ethnic bulling (Yermolova, 2015; Kretschmer, 2017). Recently, the gender differences in bullying has acquired new relevance (Efimova, 2015; Logutova, 2015; Makarova, 2017; Andronnikova, 2017). At the same time, there are very few studies on the characteristics of bullying in primary school. The purpose of the article is to identify the gender differences of this phenomenon among primary school children.

The sample consisted of 376 pupils of secondary schools in Chelyabinsk at the age of 10-11 years, of whom, 198 boys and 178 girls.

For the study of direct and indirect victimization, an adapted technique of The Multidimensional Peer Victimization Scale-24 (MPVS-24) was used, intended to evaluate direct and indirect victimization: 24 forms, victimizing actions. We have studied 5 types of victimization (physical and verbal victimization, social manipulation, social rejection and an attack on property) (Stephen, 2018).

The obtained results testify that the majority of schoolchildren have never experienced violence from classmates. Over 75% of children (75.15% of boys and 76.41% of girls) noted that they had never been exposed to aggressive influences; 9.76% of schoolchildren (10.3% of boys and 9.21% of girls) reported that they often experienced violent acts from other children.

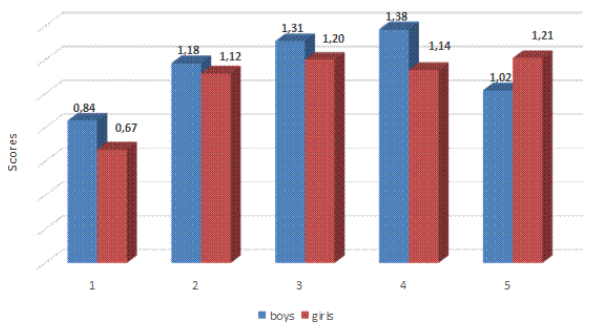

Figure 1 shows the data by types of victimization to which the subjects are exposed.

Figure 1

Exposure to various types of victimization

among primary school children

There are less cases of children physical abuse, but they are more common for boys. Among

the studied common forms of boys’ victimization, an attack on property and social manipulation were more detected. Girls are more likely to become victims of social rejection. Table 1 presents various forms of victimization among boys and girls of primary school age.

Table 1

Forms of victimization

(M ± m)

Bulling Forms |

Boys |

Girls |

Physical |

||

Kicking |

1,27±0,61 |

0,27±0,45 |

Pushing |

0,9±0,57 |

1,42±0,5 |

Verbal |

||

Ridiculing of appearance |

0,88±0,49 |

1,42±0,50 |

Mocking |

1,73±0,55 |

1,29±0,74 |

Intimidation |

1,17±0,59 |

0,75±0,73 |

Social manipulation |

||

Provocation hostility between friends |

1,57±0,72 |

1,16±0,60 |

Unsupporting the conversation |

0,93±0,69 |

1,47±0,60 |

Attack on property |

||

Breakage of things |

1,47±0,54 |

1,07±0,66 |

Theft of things |

1,4±0,64 |

11,11±0,83 |

Damage of things |

1,3±0,7 |

0,95±0,68 |

Social rejection |

||

Refusal to communication |

1,15±0,71 |

1,53±0,50 |

Prohibition of joining the game |

1,37±0,58 |

0,89±0,53 |

Rejection of initiation into secrets |

0,69±0,53 |

1,25±0,67 |

The level of standard deviation indicates a variation in the data which were obtained in both samples, there are also differences between boys and girls in the level of susceptibility to victimization.

Gender indicators of victimization are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Forms victimization among

boys and girls (%)

Forms of victimization |

Never |

once |

often |

|||

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

|

Physical |

||||||

Kicking |

78,79 |

91,57* |

4,04 |

8,43 |

17,17* |

0,00 |

Pushing |

72,73* |

69,10 |

23,74 |

17,98 |

3,54 |

12,92* |

Verbal |

||||||

Ridiculing of appearance |

75,25 |

69,10 |

22,73 |

17,98 |

2,02 |

12,92* |

Mocking |

71,21 |

74,16 |

5,05 |

11,80* |

23,74 |

14,04 |

Intimidation |

72,73 |

82,02* |

19,19* |

12,92 |

8,08 |

5,06 |

Social manipulation |

||||||

Provocation hostility between friends |

74,24 |

72,47 |

4,55 |

19,10 |

21,21* |

8,43 |

Unsupporting the conversation |

75,76 |

70,79 |

16,16 |

12,92 |

8,08 |

16,29* |

Attack on property |

||||||

Breakage of things |

72,22 |

74,72 |

13,13 |

17,42 |

14,65* |

7,87 |

Damage of things |

73,74 |

76,97 |

13,13 |

16,85 |

13,13* |

6,18 |

Social rejection |

||||||

Refusal to communication |

70,20 |

69,10 |

19,70 |

14,61 |

10,10 |

16,29* |

Prohibition of joining the game |

73,23 |

79,78 |

12,12 |

17,42 |

14,65* |

2,81 |

Rejection of initiation into secrets |

82,83* |

73,03 |

16,67 |

15,17 |

0,51 |

11,8* |

Note: * - statistically significant difference between the studied groups

at the critical level of significance P≤0,01 (Mann-Whitney U test).

There were gender differences among all forms of victimization. We present the results of the most pronounced, such as classmates’ kicking, pushing, ridiculing of appearance, mocking, intimidation, provocation hostility between friends, unsupporting the conversation, breakage of things, damage of things, refusal to communication, prohibition of joining the game, rejection of initiation into secrets.

The resulting data showed the differences in forms of physical aggression. Thus, 17.6% of boys are constantly subjected to physical aggression in the form of kicking, and girls often use a more “light” form as pushing (12.92%). There are also differences in the forms of verbal bulling: 12.92% of girls constantly experience ridiculing of their appearance, and boys are faced with mocking, (23.74%) and intimidation (8.08%) by their peers.

Social manipulation among girls is more often expressed in the form of refusal to communication (16.29%), victimization in the form of setting up other children against the victim is more characterized among boys (21.21%). Boys are more likely to attack property in the form of breakage (14.65%) and damage (13.13%) of things.

Boys are exposed to social isolation more often in the form of a prohibition of joining the game, girls point out that they are refused to communication (16.29%) and initiation into secrets (11.80%).

In general, the results of the study allow concluding that there are significant gender differences in the susceptibility to bullying for all forms of victimization. At the same time, the violation of the sovereignty of the physical space is more characterized among boys in “rigid” form; girls experience physical bullying in a more “gentle” form. Among boys and girls there are groups of children who systematically experience various forms of physical and psychological bullying, which once again confirms data on the prevalence of violence in educational institutions.

Thus, our results indicate the presence of possible gender differences in the forms of victimization. However, it should be noted that research is needed on wider samples, which allow revealing correlations between the victimization of peers and the personal characteristics of children, the peculiarities of interpersonal relations in a group and relations in the “parents-children” system in order to understand the mechanisms causing violence in educational organizations institutions and preventing this phenomenon.

Álvarez-García D., Pérez J.C.N., González A.D., Pérez C.R. (2015). Risk factors associated with cybervictimization in adolescence. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 15, 226-235. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.03.002

Álvarez-García D., Núñez J.C., Barreiro-Collazo A., García T. (2017). Validation of the Cybervictimization Questionnaire (CYVIC) for adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 270-281. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.007

Andronnikova O.O. Gender characteristics of victimization as a result of social development disorders. International Research Journal, 03 (57), 111-113.

Bochaver A.A. (2014). Cyberbullying: harassment in the space of modern technology. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 11 (3), 177-191.

Bochaver A.A., Khlomov K.D. (2013). Bulling as an object of research and a cultural phenomenon. Psychology. Journal of Higher School of Economics, 10 (3), 149-159.

Butenko V.N., Sidorenko O.A. (2015). Bulling in the school educational environment: the experience of studying the psychological characteristics of “offenders” and “victims”. Bulletin of the Krasnoyarsk State Pedagogical University. V.P. Astafieva, 3 (33), 138-143.

Butovskaya M.L. (2012). Bulling as a sociocultural phenomenon and its connection with personality traits. Ethnographic Review, 5, 139-150.

Butovskaya M.L., Lutsenko E.L., Tkachuk K.E. (2012). Bulling as a sociocultural phenomenon and its connection with the personality traits of younger students. Ethnographic Review, 5, 140-150.

Curtis, J., Bowen, I., & Reid, A. (2007). You have no credibility: Nursing students' experiences of horizontal violence. Nursing Education in Practice, 7(3), 156-163. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2006.06.002.

Efimova L.V. (2015). Gender as a social problem of society. Baltic Humanitarian Journal, 2 (11), 12-14.

Espelage D.L., Hong, J.S., Mebane S. (2016). Recollections of childhood bullying and multiple forms of victimization: Correlates with psychological functioning among college students. Social Psychology of Education. An International Journal, 19(4), 715-728. doi:10.1007/s11218-016-9352-z

Farrington D.P. (1993). Understanding and Preventing Bullying. Crime and Justice, 17(381), 458. doi:10.1086/449217

Filatov V.O., Butovskaya M.L. (2018). Bulling in the Russian school: what the students say and what the teachers know. Questions of psychology, 2, 27-41.

Glazman O.L. (2009). Psychological features of the participants of bullying. Izvestia RGPU them. A.I. Herzen, 105, 159-165.

Holt M., Vivolo A., Polanin J., Holland K., DeGue S., Holland K., Matjasko J., Wolfe M., Reid G. (2015). Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 135, 496-509. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1864.

Huitsing G., Monks C.P. (2018). Who victimizes whom and who defends whom? A multivariate social network analysis of victimization, aggression, and defending in early childhood. Aggressive Behavior, 44, 394-405. doi:10.1002/ab.21760

Joseph S., Stockton H. (2018). The multidimensional peer victimization scale: a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 42, 96-114. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.009

Kretschmer T., Veenstra R., Dekovic M., Oldehinkel A.J. (2017). Bullying development across adolescence, its antecedents, outcomes, and gender-specific patterns. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 941-955. doi:10.1017/S0954579416000596

Krivtsova S.V. (2016). Bulling in the schools of the world: Austria, Germany, Russia. Educational Policy, 3 (73), 97-119.

Logutova E.V. (2015). Gender features of victimization of senior students. Modern problems of science and education, 1 (1). Retrieved 02.14.2019 from http://www.science-education.ru/ru/article/view?id=18304

Makarova Yu.L. (2017). Gender features of the behavior of participants in the teenage bullying structure. Psychology. Historical-critical reviews and current research, 6 (5A), 181-192.

Maunder R.E., Crafter S. (2018). School bullying from a sociocultural perspective. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 38, 13-20. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.010

Monks C.P., Smith P.K., Naylor P., Barter C., Ireland J.L., Coyne I. (2009). Bullying in different contexts: commonalities, differences and the role of theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(2), 146-156.

Nesterova A.A., Grishina T.G. (2018). Predictors of school harassment against younger adolescents by peers. Bulletin of MGOU. Series: Psychological Sciences, 3. 97-114. doi: 10.18384/2310-7235-2018-3-97-114.

Novikova M.A. (2018). Family background of the involvement of the child in school bullying: the influence of psychological and social characteristics of the family. Psychological Science and Education, 23 (4), 112-120. doi: 10.17759/pse.2018230411

Obukhova, Yu.V., Gurieva, V.O. (2017). The image of the peer-victim of bullying among schoolchildren with different expressiveness of victimization. Russian Psychological Journal, 2, 8-10.

Oldenburg B., Duijn M., Sentse M., Huitsing G., Ploeg R., Salmivalli C., Veenstra R. (2015). Teacher Characteristics and Peer Victimization in Elementary Schools: A Classroom-Level Perspective. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 43, 33-44. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9847-4

Olweus D. (1993). Bullying at school. What we know and what we can do. Oxford, 140 pp.

Online Bullying Among Youth 8–17 Years Old — Russia (2012]. Cross-Tab Marketing Services & Telecommunications Research Group for Microsoft Corporation. Retrieved 20.05.2019 from https://yandex.ru/search/?clid=2186620&text=33.%09Online%20Bullying%20Among%20Youth%208-17%20Years%20Old%20%E2%80%93%20Russia%20&lr=56&redircnt=1559555743.1

Ortega-Barón J., Torralba E., Buelga S. (2018). Distrés psicológico en adolescentes víctimas de cyberbullying. Psychological distress among adolescents victims of cyberbullying. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación, 4(1), 10-17. doi:10.17979/reipe.2017.4.1.1767.

Patterson L.J., Allan A., Cross D. (2016). Adolescent bystanders' perspectives of aggression in the online versus school environments. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 60-67.

Pečjak S., Pirc T. (2017). Bullying and perceived school climate: Victims’ and bullies’ perspective. Studia psychological, 59 (1), 22-33.,

Rigby K. (2016). Bullying in Australian schools: Multiple perceptions of bullying. National Centre against Bullying Conference, Melbourne. Retrieved 10.07.2018 from http//www.kenrigby.net

Sindy R.S., Patti M.V., Susanne E.B., Jochen P., Simonevan H. (2015). Development and validation of the Multidimensional Offline and Online Peer Victimization Scale. Computer in Human Behavior, 46, 114–122. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.042

Volikova S.V., Kalinkina E.A. (2015). Parent-child relationships as a factor in school bullying. Counseling psychology and psychotherapy, 4 (88), 138-161.

Volkova E.N., Volkova I.V., Isaeva O.M. (2016). Estimate the prevalence of child abuse. Social Psychology and Society, 7 (2), 19-34. doi: 10.17759/sps.2016070202.

Walters G.D., Espelage D.L. (2018). From victim to victimizer: Hostility, anger, and depression as mediators of the bullying victimization-bullying perpetration association. Journal of School Psychology, 68, 73-83. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2017.12.003

Yermolova TV, Savitskaya N.V. (2015). Bullying as a group phenomenon: the results of bullying research in Finland and Scandinavian countries over the past 20 years (1994– 2014). Modern foreign psychology, 4 (1), 65-90.

1. Doctor of pedagogical sciences, Professor, South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University, Chelyabinsk, Russia , Contact e-mail: evgvolch@list.ru

2. Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Associate Professor, South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University, Chelyabinsk, Russia , Contact e-mail: zhukovamv@cspu.ru

3. Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Associate Professor, South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University, Chelyabinsk, Russia , Contact e-mail: frolovaev@cspu.ru

4. Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Associate Professor, South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University, Chelyabinsk, Russia , Contact e-mail: shishkinaki@cspu.ru

5. Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Associate Professor, South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University, Chelyabinsk, Russia , Contact e-mail: shishkinaki@cspu.ru